THE MAN WHO OPENED HIS DOOR TO LANCE KNIGHT HAS PASSED

Share

Pak Hosein, the stately old gent who opened his humble home to surf adventurer Lance Knight in the Mentawai Islands back in 1991, has passed away. Pak and his wife Ida would go on to host hundreds of surfers in their basic homestay right in front of the wave that would take Lance’s name.

And Pak’s simple act of hospitality, welcoming a stranger who arrived unannounced on their shores in a dugout canoe, represents all that is good and decent in the warm relations enjoyed by Australian surfers and our Indonesian hosts.

Pak and his family moved from the Sumatran city of Padang out to the Mentawai Islands in the ‘80s as part of a government transmigration program to disperse the Indonesian population more widely. He was offered a small land grant and set up a trading shop in the village of Katiet. His chance encounter with a Newcastle sea captain, and the friendship they formed, would change the course of both their lives.

Lance Knight was a salty old sea skipper down on his luck, having lost his job and his girlfriend in quick succession, when he decided to check out some islands just south of Nias in search of waves. The welcome he received in those remote islands and the wave he discovered altered the world of surf travel forever. But it was a small miracle that he made it out to the islands at all.

When he arrived in the West Sumatran port of Padang, after hitching a ride on a cargo ship from Malaysia, Lance was picked up by a truckload of soldiers and became the guest of honour at Padang’s gala “Tourism Week” celebrations (mainly because he was the only tourist they could find). The next day he fell in with a local rock star and enjoyed a big night out on the town on a tour of Padang’s nightspots. But he was still no closer to getting out to the islands.

Eventually, he met an Iranian doctor, Dr Manir, who conducted regular medical clinics out in the Mentawais, and hitched a ride on his charter plane, armed only with two surfboards, a backpack, a bag of rice and a bottle of water. He was deposited on a grassy airstrip and while Dr Manir trekked off into the jungle, Lance flagged down a passing dugout canoe skippered by a fisherman he knew only as Mr Basur. Through hand signals and a small exchange of rupiah, Lance managed to convince Mr Basur to take him to a likely bay he had scoped out on the southern end of the island of Sipora. But before they could make it to the bay, a looming storm and engine trouble drove them to seek landfall through an obliging break in the reef. Lance found himself staring into the almond-eyed barrel of a wave that would become famous around the world and carry his name. The entire village of Katiet came out to greet him when he reached shore.

“At first, I was surrounded by children until my eye caught sight of a tall, regal-looking Indonesian gentleman walking towards me offering me his hand,” Lance recalls. “I shook hands with Pak Hosein and because I couldn’t speak much Bahasa all I could do was tap my chest and say, ‘Nama saya Lance,’ (My name is Lance) and pointed to the surf,” he recalls. “Before I knew anything else, Pak had organised my backpack, supplies and surfboard being carried off up the beach to his house where I was introduced to his wife and surrounded by what appeared to be the whole village. After evicting their children from their room, I was shown a very tiny bed.”

Though touched by the hospitality, Lance was more interested in the wave out front. “I managed to retrieve my board and headed back down the beach. I’ll never forget the attention the canoe builders gave my surfboard as I pulled it out of the cover, picking it up, tapping it and running their hands over it.”

Local kids climbed the trees and lined the beach, cheering as Lance surfed the wave alone. As far as anyone knows, the wave had never been surfed before, and he enjoyed it to himself for two weeks, from three to six feet. When the wind swung onshore he decided to trek across the island to try and find the bay he was originally headed for. Thus, he also discovered Lance’s Left. “It was Pak who took me through the jungle to the bay on my map just before Martin Daly found me,” says Lance.

Two weeks into his stay, a western dive boat pulled up and two figures jumped overboard with boards. Martin Daly and his crew on the Indies Trader had been salvaging a bulldozer that had fallen off the side of a logging barge, when they decided to go looking for waves themselves. Martin invited Lance aboard, offered him a beer and a steak dinner, insisted the wave be called Lance’s Right, and the seeds of the great Mentawai surf boom were sewn. Martin would go on to command a fleet of luxury charter boats in the Mentawais and his old dive boat the Indies Trader would receive a striking makeover for the Quiksilver Crossing, a five-year, global voyage of surf discovery.

Even as the Mentawais became a household name, sparking a gold rush of charter boats and land camps, Lance didn’t return to the islands for over a decade, busy as he was fathering two boys and earning a living skippering the cargo ship Island Trader from Yamba to Lord Howe Island. In 2004, Surfing World decided to do an on-location issue in the Mentawais, aboard a converted navy boat called Huey, rumoured to have once been the pleasure boat of Tommy Suharto, son of the former Indonesian president.

By then, Mentawai boat trips had become a surf mag staple and so, along with young Aussie pros Danny Wills, Dean Morrison, Mitch Coleborn, Jay “Bottle” Thompson and a barely pubescent Matt Wilkinson, I decided to track down Lance and invite him along for a nostalgic return trip to his wave. He was incredulous, beyond stoked. I have a vivid mental image of Lance and Wilko, side by side in the back of our bemo, the veteran surf traveller and the Indo virgin, both taking in the teeming chaos of Padang, eyes agog.

We reached Lance’s Rights at dawn after a bumpy overnight crossing from Padang, as a dark, angry squall whipped the lineup. Lance stood at the bow of the Huey, eyes narrowed into the maelstrom taking it all in, flashbacks of memory whizzing through his mind. Deano was first over the side and, with a human yardstick in the lineup, revealed the surf to be a solid six to eight feet, grey walls capping outside the ledge, then spilling over into outrageous barrels. Lance wasn’t far behind him, a bright yellow helmet his only concession to self-preservation and advancing years.

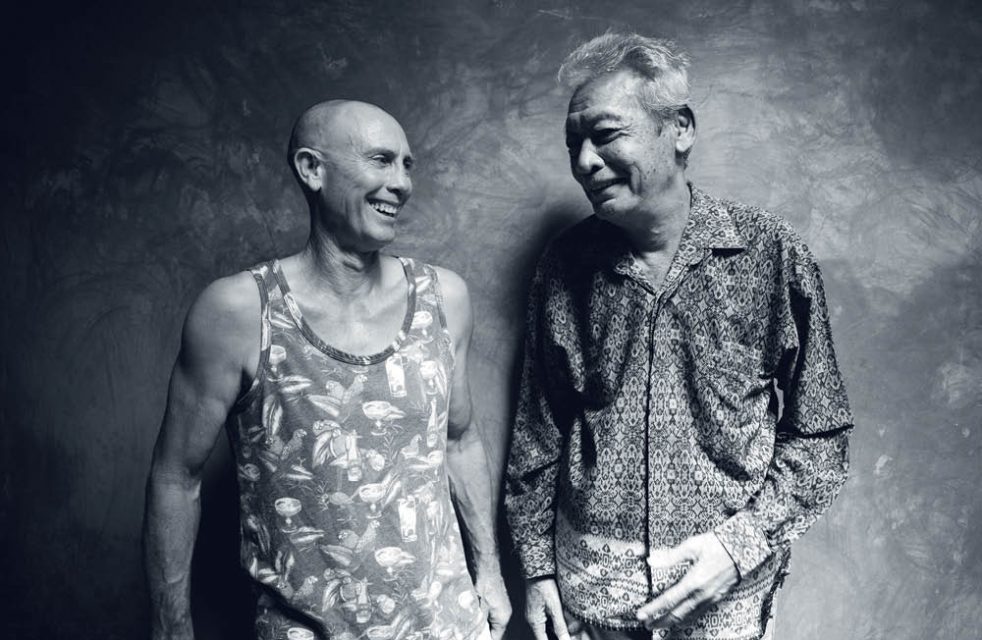

Later that morning we went ashore and Lance found the old hut he’d first stayed in, now half-buried under beach sand. Further inland, after asking around, he found the smart new home of Pak Hosein, knocked on the door and waited. His wife Ida came to the door, lost for a moment in the shock of recognition, then called excitedly for her husband. I stood to one side awkwardly, a gawking intruder to their private moment. Pak wasn’t dressed for company, in white singlet, shorts and bare feet, and regarded his pale visitor curiously for a moment, his leathery features finally creasing into a smile. “Lance, Lance,” he breathed quietly, patting him warmly on the shoulder. The old sea skipper looked suddenly boyish. They embraced, exchanged excited chatter in Lance’s broken Indonesian and Pak’s small moans of disbelief.

Lance was pleased to note Pak and his wife now had a fine, cement home, far superior to the old shack he had stayed in over a decade earlier. They had a tidy little business renting rooms to surfers. Surf Aid had arrived in the village, bringing much needed medical aid and mosquito nets, greatly reducing malaria. His qualms about having opened up the area to surf tourism and development were quelled by these small signs of positive benefits for the local people.

I returned to Katiet with Lance again in 2014, another decade on, this time for a Red Bull documentary about his storied surf discovery, with acclaimed filmmaker Peter Hamblin (of Let’s Be Frank, fame). In the name of authenticity, we caught the public ferry over from Padang and stayed with Pak and Ida, rather than high speed transfers or any of the luxury surf charter boats or resorts. This time, Lance was accompanied by his teenage sons Tasman and Keelan, and his Indonesian wife, Tursilah. Again, Lance stood up the front of the local longboat that took us from the ferry to Katiet, squinting into the distance trying to discern the old familiar coastline. “Pak will be the first one to greet us on the beach,” he predicted. “He always is.”

Sure enough, as our boat cruised up onto the sand, a tall stately figure stepped out of the shadows of the coconut trees. Pak Hosein and Lance embraced warmly and Lance’s Indonesian was now proficient enough to allow a spirited exchange of news and jubilant introductions to Lance’s family.

Now there was a string of homestays along the beachfront, one empty ghost town of a high-end resort (abandoned after a bitter feud between rival westerners), and a budget bamboo surf camp with a simple little café. Pak and Ida were getting on in years and though Ida insisted on cooking for us every meal, eventually, one by one, we started drifting up the beach to the café where they had a menu, brewed coffee and internet. I watched Pak wander up and check out the new establishment curiously, trying to discern what its attraction was and how he could catch up. His sons were now involved in the business, and I’ve no doubt this next generation will usher Hosein’s Homestay into a new era.

Lance was deeply rattled when he gave me the news that Pak had left us. It was believed Pak had suffered a fall and a stroke and had been bedridden for some months. He was 78, a ripe old age in a part of the world where infant mortality rates are high due to malaria and mal-nutrition.

In this age, when a country as wealthy as Australia repels and locks up some of the most desperate and disadvantaged people in the world fleeing war and persecution, and a large chunk of the world’s population are regarded with suspicion because of their religion, it’s worth remembering that humanity is not always so callous. It’s ironic, that Pak and his family, Muslims, lived up the point from the main, predominantly Christian village of Katiet, because of their different faith. But that separation placed them squarely in front of the wave Lance pioneered and put them in the perfect position to offer the first accommodation to visiting surfers.

“The passing of Pak Hosein will send a tsunami of sadness around the world of surfing,” Lance texted me. “The beach at Katiet will become his shrine, especially to me. A great man of the Mentawai people, a majestic and humble human being who shared not only his home with us all but his heart. I have lost a special friend.”