What It Feels Like To Paddle Bass Strait

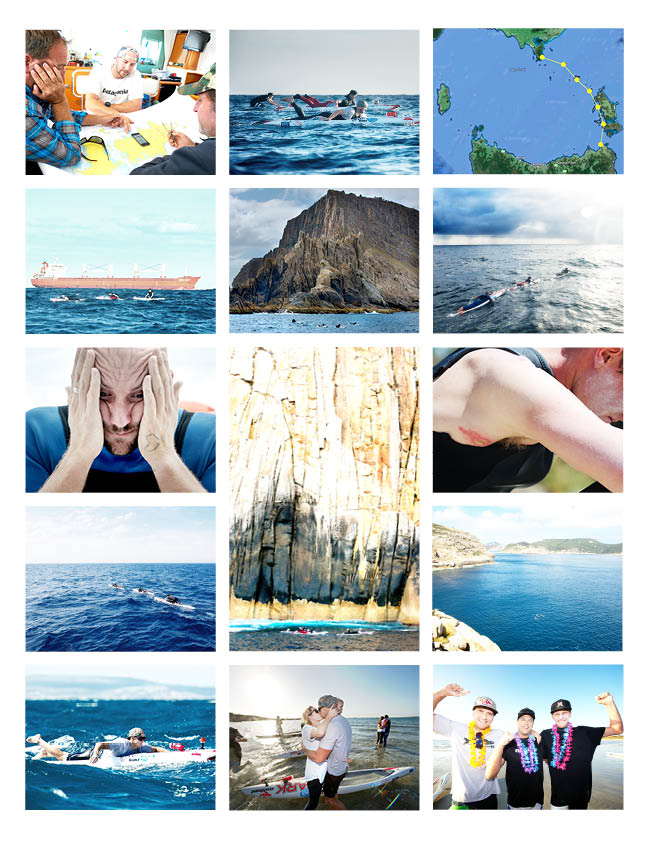

Paddling sucks at the best of times. That’s why surfers found the rock-off. Now imagine paddling for six days straight… and not catching a single wave. Mad, right? Wrong. Zeb Walsh (31), Brad Gaul (34) and Jack Bark (19) are three mates from Torquay, Sydney and California respectively who recently did just that, they paddled, wait for it – Bass Straight. Yep, from the mainland to Tassie.

The Strait is often crossed by ships, yachts, trawlers, kayaks even Orange-bellied parrots. But never before had it been crossed on paddleboards. That was until Zeb got the idea and by March this year the three lads were standing on the sand at Wilsons Promontory about to begin an adventure over 320 kilometres long to Cape Portland, Tasmania. All three have won the famous Molokai to Oahu paddle race in Hawaii. But that was only 52 kilometres. The following tale is Brad’s account of what it feels like to paddle your body to breaking point, both physically and mentally, in one of the most hostile environments on Earth for nothing more than the sweet reward of an oceanic adventure and the world’s worst case of armpit rash…

Zeb lives in Torquay so the Strait is his backyard. He’d been dreaming of this paddle for years. The three of us got together and said, “Yep, let’s get across there.” After months of preparation, standing on the beach was an insane feeling. We had that moment where we looked at each other and went, this is it, we’re doing it. Nervousness. Excitement. The whole lot. We jumped into the icy Tasman and left and it looked spectacular with a beautiful blue ocean underneath. A seal even followed us for hours from Wilsons Promontory.

Land began to fade behind and the further we got out toward the horizon the more the side-chop grew. It was our first taste of how much the wind would control paddling conditions… and morale for that matter. Despite a relatively flat swell, the wind would get so strong at times there’d be three-to-four foot chop. Six hours of going up and over a chop, the nose of the board getting caught by the wind while one arm’s trying to stabalise and the other’s trying to paddle is torturous and heartbreaking at times. The water was hitting my face so fast the wind-chill felt like daggers. Some mornings we wore sunnies at 5:30am simply to protect our eyes.

The way the currents and tides pull in the Strait is like nothing I’ve ever experienced. It can pull up to three-and-a-half knots, almost 10km/h. For much of the first day the current was working against us and it turned a five-hour leg into a seven hour battle. When you get caught in a current you just feel like you’re in the hands of Mother Nature. She’s calling the shots, you’ve just got to do your best to deal with them.

What people might not realise is the Strait is dotted with islands. We’d leave each morning and have to make the next island by nightfall. Jack, fell really sick on the first day. He was in a bad way. Whether it was jet lag, being in a foreign country or the stress of the challenge or a combination of them all, he very nearly capitulated. We got stuck on the first island, Hogan Island, for two days because of 30-knot headwinds and that was the recovery Jack needed. He’s incredible for such a young bloke. A huge achievement.

Muscle fatigue was the first thing to rattle my body. Rashing too. Then my knees went and my neck completely locked up. It’s a really unorthodox position to be in for such long periods of time. It’s like being in the Mentawais and surfing for five hours because the surf’s pumping. Now, do that for seven hours and again the next day, and the next day and the next. Imagine what that’d do to your neck and shoulders. And to make matters worse, instead of throwing on boardies you have to put on a wet wetsuit and booties for the freezing conditions.

As the paddle went on, our bodies went into complete survival mode. That’s where you learn a lot about yourself. The emotions came on without even knowing. One minute I’m spiraling into a really down moment and I’d start crying uncontrollably. Then 10 kilometres later I’d be back on a high thinking, how good’s this? We all went in believing we were pretty tough, doing Molokai you have to have some sort of mental toughness. But we came out of it – Enlightened.

All we were using was a GPS to navigate and our support boat. There’s no landmarks for much of the time to gauge our bearings and we’d often have to paddle in arcs from island to island to make landfall otherwise the currents would send us out into the Tasman. The scenery is spectacular. Some places were like being in the Whitsundays but with cold water. You’ve got that bora bora blue water, pristine white beaches with wallabies hopping along the sand. But while that sounds like paradise, there were islands we couldn’t land on; one infested by snakes and others just masses of rocky outcrops. We’d also teamed up with Tangaroa Blue to remove and record any rubbish in the Strait.

Sleep was rough. It was on the boat in a bed the size of a kitchen bench – except there’d be two of us squeezed in there. It felt as though I was never completely dry. The skin of my feet peeled off from being wet for so many days. We were always putting on a cold, wet wetsuit at 5:30am, that’s always been a pet-hate for surfers. If you’ve done that six times in a row you’d know about it.

Paddling into Deal Island was one of the most beautiful things I’ve ever witnessed. The island only has two caretakers on it and a lighthouse atop a 1000ft cliff. We paddled three feet away from the cliff, the swells would hit and float us metres up the cliff face and then fling our 12-foot boards along. Looking up and seeing the size of that land, you couldn’t help but feel completely insignificant.

Midway through we paddled past a seal colony. Hundreds of them were perched on an island and we gave it a wide berth of about a kilometre, knowing exactly what they attracted. Halfway around we began wondering what the hell Dean [the boat captain] was doing with the boat as he moved back and forth in a bizarre way. Later that day he said he spotted a huge shadow following us. He was keeping the boat between us and the shark. Luckily he didn’t say anything because we still had 30 kilometres to go until we reached land and imagine paddling that distance in fear of something coming up from beneath you. In saying that, I remember being in so much pain, lying back on my board and falling off and feeling weightless in the ocean and thinking… just take me. Getting back on your board in times like that was the hardest thing.

The last day we had to gun it across the channel otherwise the weather would lock us on the island for three days. That was a 66km leg. It took 9 hours. For the last stretch the boat couldn’t get close because the currents were so strong it would’ve flipped. So, after paddling for five days straight, for the last 66km we only had one drink bottle. I spotted these strange white lines in the distance during that leg. They got closer and closer but in fact it was us getting sucked towards them. They were three-foot stationary waves breaking over shallow rocks, completely fueled by the tidal change. We got sucked into them, one after the other. It’s like nothing I’ve ever seen. It was like someone had let Curl Curl lagoon out. The depth is what makes these waters so dangerous. In the middle of nowhere you could almost see the bottom it was so shallow. For the last 14 kilometres, Zeb and I paddled without fins after they were ripped out from the rocks.

Making the beach was incredible. I get so used to the feeling of winning being the reward but this was a complete sense of achievement and relief. Yes, we’ve made it. There’s a bond now between us boys that’s pretty unexplainable. When you go through survival mode with someone, there’s a certain part of you that’ll always be connected to that time and place and person. It was something mentally toughening more than anything else. Everyone has a pain threshold but it’s not till you go beyond it that you realise what’s really possible and it proves the power your mind has over your body. It instantly changed the way I look at day-to-day life, even as simply as the way I run my business. You learn so much about values, patience and the insignificance of some things when you push your body and mind to a place like that.