The Short History Of Fins

Share

There’s probably no more common means of laceration in surfing than fins. If everyone surfed finless the company that makes medical sutures would go broke overnight.

Tom Blake’s 1934 invention had no sharp edges. Paradoxically, motor vehicles of the time were loaded with fittings that could slice you open – go figure.

Simon Anderson aside (yes, I’m getting to him, settle down), there’s not much prestige accorded to fin inventors. People like George Downing, Woody Brown, Wally “Hot Curl” Froiseth and Joe Quigg tend to be seen as nutty professors when compared to the design gods who make the board itself.

So how do fins work? Well, Surfresearch puts it this way – “Surfboards are planing hulls, planing on the meniscus, the barrier between the surface of the wave and the air. Conversely, the fin is hydrodynamic: that is, it travels through the water, and thus performs according to displacement hull principles.” So, all clear? Good.

Tortured genius Bob Simmons took Blake’s keel shape and made it look more like a fin. He also came up with twin fins. He died young, and some kind of cerebral Alexandria Library of fin genius disappeared with him.

But along came Renaissance Man: Greenough, fiddling around in wood shop at school, added flex and more back-sweep, reputedly modelling the high-ratio fin on the tails of pelagic fishes. He attached them to kneeboards – McTavish then used the same shape on surfboards. Greenough was, as usual, way ahead of his time – in the early sixties, almost everyone surfed a ‘D’ fin. They looked about as hydrodynamic as a roof tile: Greenough’s looked sleek. Mutations came and went: the Bat Fin, Tunnel Fin and Gun Fin. Greenough did another sleek one. Then the Hatchet, the Weber Turbo and the Tiger Tail. And Greenough did another sleek one.

Single fins dominated the world for yonks. There was little evolution – mostly just gimmicks. In ‘55 Velzy-Jacobs did a thing called a butterfly fin (imagine two singles glassed together at the bases to form an upside-down ‘V’). It disappeared without a trace, and fair enough.

The ‘70s brought us fin boxes – Simplexes and Bahnes. The little screw would always rust up and no-one knew if the thing was supposed to go forward or back but it was nice to have the option. The one durable thing to emerge from this era was coloured laminates, which look ridiculously cool but have nothing to do with performance.

But an alternative version of the ‘70s was bubbling away on the backburner. Steve Lis added the evolutionary leftover of the keel fin to his fish design. MR took that setup and added DNA from Abellira, Brewer and Ben Aipa to create the twins that got him four world titles.

In ‘81, Simon Anderson took the twin’s symmetric foils and invented the thruster. In ’84 I nearly lost a nipple to the back fin of an Energy square tail, but no-one offers me a dollar every time I say “nipple.”

Glen Winton’s 80s-era quads worked for him but strangely fell into disuse until about 2011 (His webbed gloves, however, were dead on arrival.) The other thing that happened in the ‘80s was Cheyne and his Lexcen-designed “Starfin” winged keel. Did it work? As with all things Cheyne, the hook was in the mystique.

What’s left to cover? Five and zero. The Campbell Brothers’ Bonzer had five: invented in the ‘70s but only now getting the recognition it deserves, the Bonzer had one big ol’ single fin in the centre, and double finlets under the rails. Frankenreiter made ‘em look cool in ‘Shelter’ (nearly as cool as buying beers in the Campbell Bros boardstore in Haleiwa).

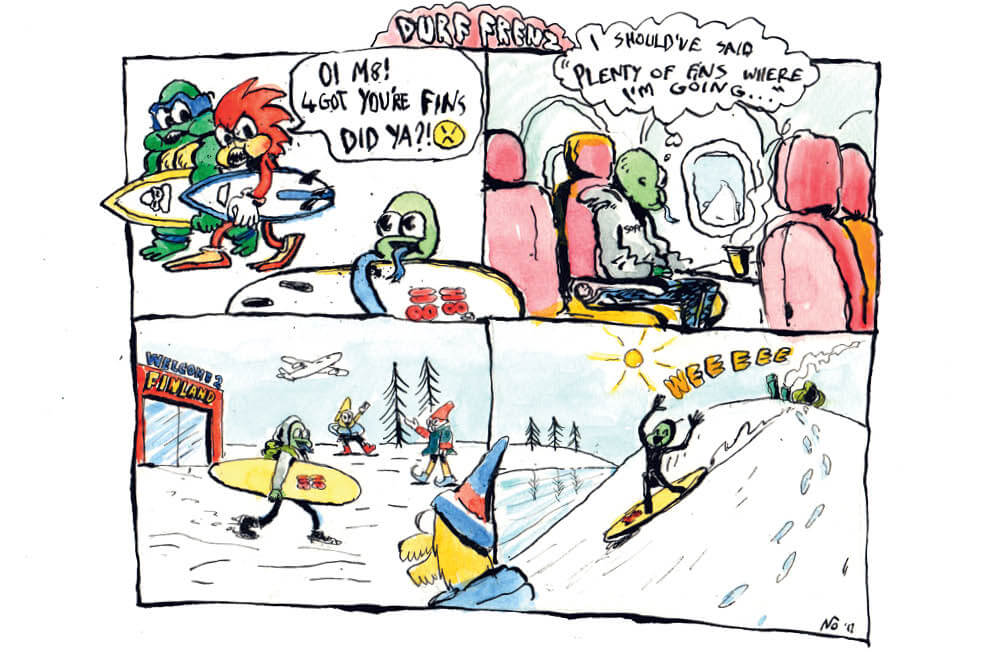

Removable fins are mostly noteworthy for their diabolical add-on: a key that always strips itself. And if you want to get the jump on mates putting their fins in as the boat approaches Lances on Day One, there’s the powered fin key, an invention that looks offensively first-world as the kids paddle their dugout canoes towards your charter.

But perhaps the greatest modern contribution to fin placement belongs to Derek Hynd, who decided one day to leave the bloody things in the car.