The Short History Of Norfolk Pines

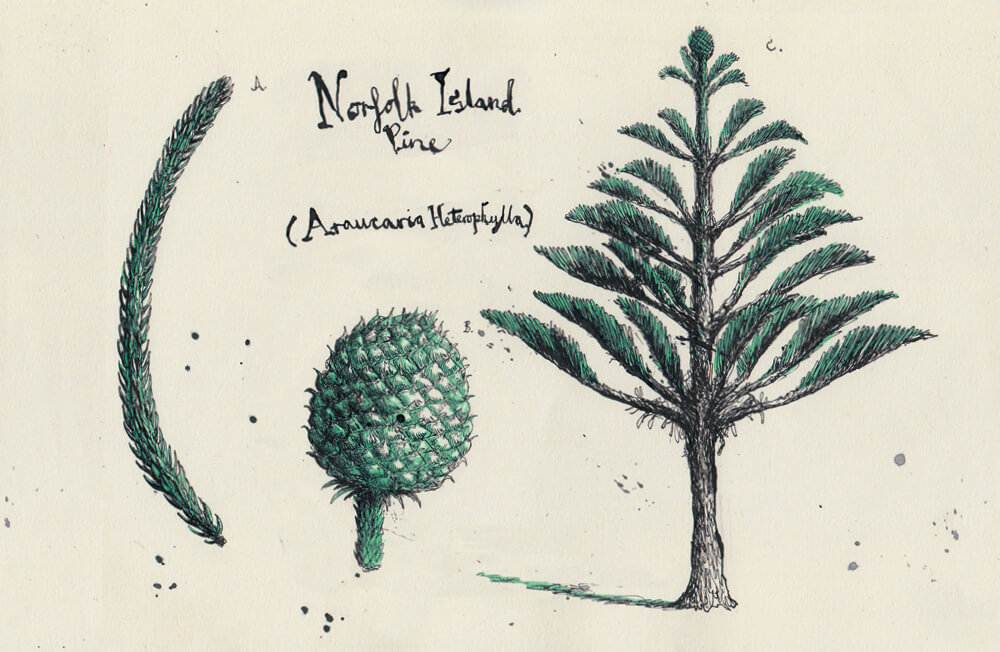

There are some subtle signifiers that attach themselves to surfing through mysterious processes of convergent evolution which even David Attenborough can’t decipher. Bakeries. Ropes down cliffs. Campsites. Things that may have existed without surfing, but which invariably turn up when there is surfing nearby. To this list we should add the Norfolk Island Pine, which is in fact not a pine at all but a conifer, and which appears on almost every temperate coast where there’s good waves.

The geographical coincidence is astonishing. Consider: Manly, Avalon, Whale Beach, Burleigh, Esperance, Raglan, Peru, Chile, the northwest coast of Mexico, Portugal, South Africa, Northern California and Florida. Since Brazilians began repopulating the surfing universe, Norfolk Pines have appeared all over Rio. There’s even one on Valentia Island on the southwest coast of Ireland, which may be the northernmost specimen in the world.

Local councils love Norfolk Pines for the stately atmosphere they lend to even the dullest main drag. Some councils in America, however, have begun banning them because of their great height and susceptibility to lightning strikes. The logic on display here is less than compelling: lightning being lightning, it’s bound to strike the next-tallest thing if there’s no Norfolk Pines about. And in most counties, that’s likely to be a pickup truck.

As long as they get fresh water when they’re pups, Norfolk Pines will grow in ordinary beach sand and can reach up to 70 metres tall, which is a long way to climb when you’re a grommet and someone has placed your pushbike at the top. The even spacing of their boughs makes such a climb possible for both children and drunk adults. They’re ruler-straight and symmetrical, thus lending themselves to civic use as Christmas trees, although they’re yet to reach their full potential in the field of surfcam placement. They cast jagged, triangular shadows on hot days. A town with an avenue of Norfolks, when viewed from a distance, appears as a distinctive serrated edge on the horizon.

Among the many other firsts he recorded, James Cook is the first European known to have sighted Norfolk Island and its eponymous pines. On his second voyage hereabouts in 1774, he saw expansive forests of these perfectly straight trees with treadlies lodged in their branches and thought they’d make excellent masts and yards for shipping. It’s a commonly-held myth: the timber is too soft and flexible, unless you fancy sailing the seven seas on some kind of fantastic elastic springloaded crazy ship.

Unlike almost any other tree on a surfing coast, Norfolk Pines are useless as surf indicators. They do not bend, under even the strongest winds, and their foliage is way too stiff and heavy to give the tiniest clue to wind direction or strength. Gales passing through Norfolks raise an unearthly hissing sound, but the only other noise they emit is the racket of roosting galahs. They will ruthlessly ensnare any football kicked into their canopy, and even rocks hurled at the trapped footy will stay up there… for a while.

Apparently Norfolk Pines produce edible nuts, although no-one anywhere, ever, is recorded as having eaten one. Their other main byproduct is huge mounds of discarded fronds known as monkey-tails, which seem never to decompose, and are therefore useless for mulching but quite handy as a base for eating fish and chips, or even a quick roll with a friend after the pub closes. Why get all sandy if you don’t have to?