So Thank God For Cape St. Francis

Legendary surf filmmaker Bruce Brown is no longer with us. The ‘Father of surf films’ passed away peacefully in Santa Barbara, California late yesterday afternoon, leaving behind a life’s work of iconic surf films that helped to put our culture on the map. Bruce inspired the stoke for adventure in so many generations of surfers, and it is this legacy which remains timeless. Six months ago, senior writer Mike Jennings was fortunate enough to join Bruce for his last ever interview in SW Magazine. Read on as we celebrate the life of Bruce Brown and 50 years of The Endless Summer…

First of all, let’s get one thing out of the way, and that’s that interviewing Bruce Brown is an absurd notion. A ridiculous idea that shouldn’t be possible. It’s like someone saying you can interview your favourite childhood memory. Or that a rad cartoon character from a show you watched as a kid was actually a real person you could call on the telephone and ask a bunch of things. Bruce Brown isn’t a real, living, breathing person like you, or me, or the actors on Home and Away. Bruce Brown is that hilarious voice of Endless Summer. Bruce Brown is creator of the greatest surf film of all time. And it is the greatest surf film of all time.

When John John Florence and Blake Kueny released their most anticipated profile surf film, View From A Blue Moon, at the end of 2015, there were a few people brave enough to call it the best surf film ever made. And it was a fair call to make. It featured the best performance we’ve ever seen in a surf movie, it was filmed on 4K, and it was a fun John C Reilly narrated romp around Hawaii and the rest of the world with our most talented surfer to date. What’s not to love? But whenever any big surf movie flirts with the title of greatest surf film ever put together, it always brings us back to Endless Summer. Despite being 50 years since its first theatrical release, the film remains completely relevant to our surfing lives.

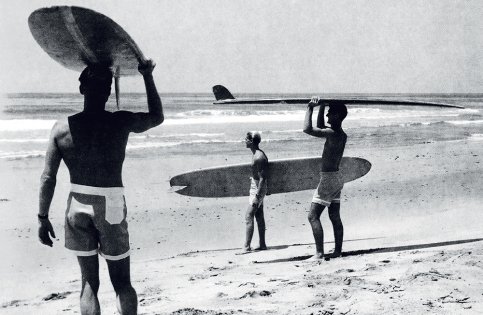

The surf performances, the cinematography, the waves, they’re all mediocre in some regards when you compare them to today, and our world is largely unrecognisable to the one that Bruce and hot-doggers Mike Hynson and Robert August flew around back in ‘62, but despite all that, there is something that remains eternally relevant – the spirit. The indescribable something that beats out of the heart and through the veins of anyone who calls themselves a surfer, regardless of the generation they come from. So much so that it’s hard to work out if this knockabout-fun which defines us was first captured by Brown’s Endless Summer, or did he actually help to create this feeling in the first place? We’re talking about the sense of adventure that core surf brands like Billabong and Rip Curl harness in their most famous taglines, “The Search” and “Only A Surfer Knows The Feeling” respectively – for those that came after the film’s release, which is most surfers on the planet, it’s a chicken and the egg conundrum that doesn’t actually matter. The influence of this film on surf culture is unquantifiable, whether you were introduced to it directly as a kid who knew stuff all about surf culture, or you were introduced to surf culture through some other video, magazine, or web clip that itself could trace its lineage back to Bruce Brown and that immortal sequence of Robert, Mike, and Terrence of Africa walking over the dunes for the first glimpse of Cape St. Francis. A film being compared to Endless Summer is the biggest compliment in the medium. And it will remain a compliment in a decade when the next best surf film ever gets compared to Endless Summer then, and in two decades, three, four etc. It’s like calling a new Hollywood film better than Citizen Kane, how do you even begin to… nevermind.

So, interviewing Bruce Brown is absurd right? Not possible. Except when there have been 50 years since his most famous film’s release, and someone makes a book to commemorate that milestone, and a couple of emails later you’re being introduced via a grainy Skype feed by a lovely PR person to a very real, very living, breathing legendary, pixelated, but legendary, Bruce Brown sitting on a couch and staring back at a pixelated version of you. You’re talking to the Endless Summer voiceover, that classic Bruce Brown drawl with: The. Perfect. Comedic. Timing. You’re interviewing a favourite childhood memory.

MJ: How’s it going Bruce?

BB: Well, I’m upright.

Yeah? I’ve got to tell you, this is quite a thrill. Growing up in Australia, I think the first surf video we had in our house was Endless Summer, introduced to me by my dad, and we’d watch it every weekend. It was the first surf video that made me fall in love with surfing, so I’m a little bit nervous and thrilled to be talking to you.

Oh, well thank you, just be thrilled I’m still alive.

Can you take me back to your first memories of surfing, when you first fell in love with surfing, and how that led to making movies?

Well, I started filming mainly to show my mum and dad what surfing looked like. Because nobody was really surfing where I lived, so I used to steal a paddle board off the docks out in the middle of this bay and paddle off to the entrance channel. It took me a week before I ever caught a wave on this little paddle board, and then I remember paddling home and running into the house saying, “Oh mum! God! You should have seen me out in the surf.” At the time, if you were a surfer, you were a bum, a loser. So imagine me today, now it’s gone mainstream. I mean, ads and Wall Street, everybody’s a surfer and proud of it, and I’m proud for what it’s become.

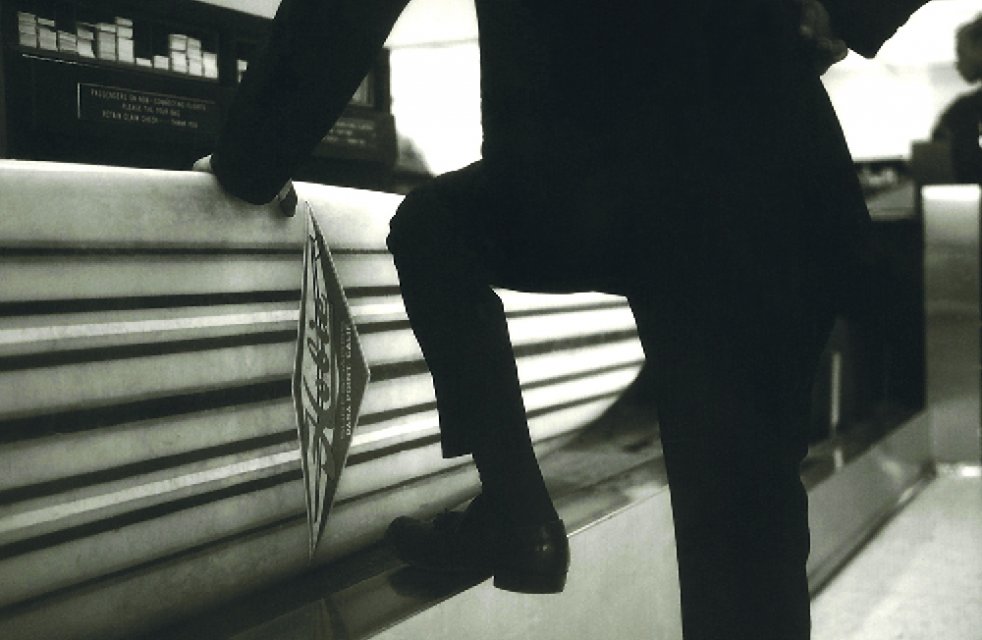

And you grew up learning to surf in the Dana Point area, right?

Yeah, south Orange County, Dana Point, I lived in Dana Point and surfed Trestles, and I was a lifeguard in San Clemente. And one thing led to another, joined the navy on the way to get to Pearl Harbour, so that was my first trip to Hawaii, as a submarine sailor. And gee, I’ll never forget that, it was like I died and went to heaven. You know? Slept on the beach at Waikiki, the water was warm, it was like paradise. I made a film while I was in the service and I used to show it at Velzy’s shop in San Clemente and charge a quarter. And so Velzy’s the one who got me started making 16mm movies. He put up 5,000 bucks and that was the total budget for Slippery When Wet, my first one, that covered my living expenses for a year, the trip to Hawaii, and all expenses.

So when Dale Velzy got you happening with Slippery When Wet, did you know that you were on the pathway to making surf movies or were you just stoked that you were going to get a trip to Hawaii to make a movie for Velzy?

Yeah, I had no idea it would go any further, but after that was over we actually made enough money to make another movie. And then Velzy stepped away and I went out on my own from there on, but yeah he’s the one that really got me started.

Did you see it as a career? Or was it just something to do? Something to keep you surfing?

It was something that could keep me surfing. You know at the time at Dana Point, Hobie made surfboards and Severson had a magazine, and he made movies too, and I was friends with Greg Noll, and ah… it was almost becoming a way to make a living and stay at the beach. I had no idea it would become a whole career, but… it did… apparently.

Haha, sure did. And then when you went on to make Surfing Hollow Days, and you went down to Pipeline with Phil Edwards to film him surfing it for the very first time, did you have any indication at the time that Pipeline would become, well, Pipeline?

Haha, sure did. And then when you went on to make Surfing Hollow Days, and you went down to Pipeline with Phil Edwards to film him surfing it for the very first time, did you have any indication at the time that Pipeline would become, well, Pipeline?

No, not really. I figured after like five people died that’d be the end of it. But, so it turned out, the same day that Phil rode that wave and came out of the water and went, “That’s enough for me, I’m not going back out there,” that same day the word got out and other people started showing up and going over the falls, and suffering horrible wipeouts, and that was the beginning. It was funny because Pipeline – Severson and Bud Brown and I were like competitors making surf movies – so I called it “The Pipeline”, Severson didn’t like that because he wanted to name the place, so he called it Banzai Beach, and we kind of finally relented to start calling it “The Banzai Pipeline”, and then it finally just became “The Pipeline”, but we were the ones that named it. And then we named Velzyland after Velzy, well it’s the only place in all of Hawaii where, because he was so well respected, that the name stuck, ’cause most of them went back to whatever the local people called the place. So I was kinda proud of that, that it stuck because of their respect for Velzy.

Had you been watching Pipeline in the days preceding, or even the winters preceding? Was it a spot that people talked about or looked at?

I think that with the surfboards of the day it just didn’t look like a place you could really surf. In fact, before anybody surfed there, we lived in this vacant lot that was right there at The Pipeline. Pat Curren and Al Nelson and a bunch of us slept on this vacant lot. I remember Pat Curren had a mattress in a tree, right there at The Pipeline. The lot belonged to this lady whose dad was a doctor, so we got permission to camp there.

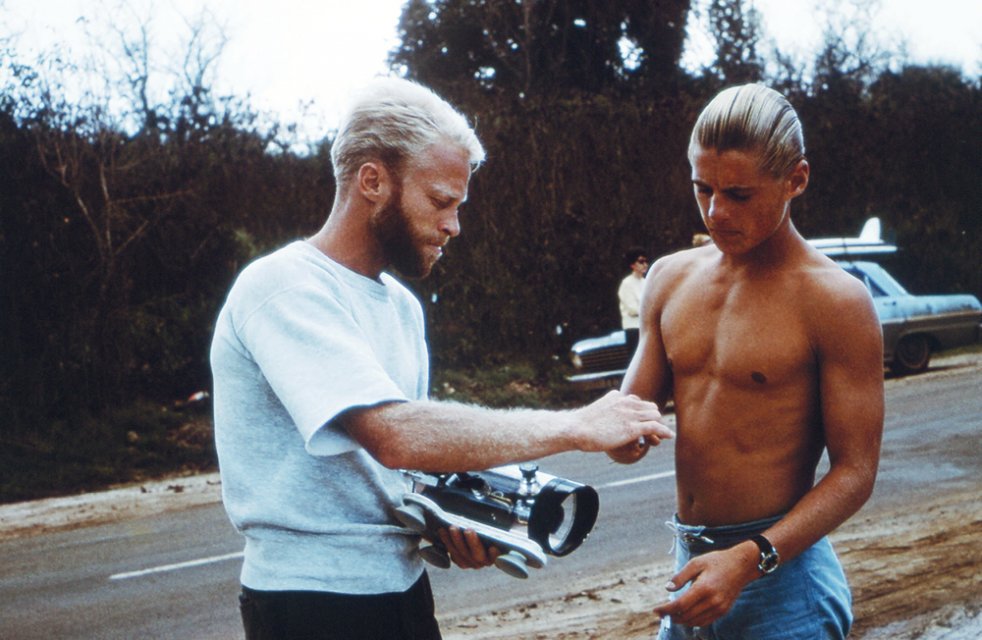

And then when it came time to make Endless Summer, you’d made five or six movies by then, and then obviously Endless Summer became… Endless Summer. Did you have a different approach to making Endless Summer from the very beginning, with the concept and financing and all of that?

Yeah, I just always figured I needed more time to make my movies, because, you know, we’d shoot ’em and then edit, and then go on the road and show ’em like 50, 60 times at different venues around Southern California, so I thought if I could take two years to make a movie I could make a much better movie, and so we put out Water Logged in the meantime to hopefully earn some money to finance Endless Summer. But, you know, the concept was going to the Southern Hemisphere where it’s summer when it’s winter in California, and then of course most of the surf trips I ever went on to some exotic place, there’d be no surf.

Yeah!

So thank god for Cape St Francis or we would have come back with not a whole lot of great surf footage, except for Hawaii, which, we’d already seen, so…

Yeah, I mean, I remember growing up in Australia, that part being a highlight to me, but the Australian section’s a whole lot of “Shoulda been here yesterday” stuff, and not a lot of nice waves.

Yeah, I had horrible luck in Australia, you know, go to good surf spots and it’s just not the right day.

So how long were you shooting it, and then how long between shooting it did it take to put together and finally release it?

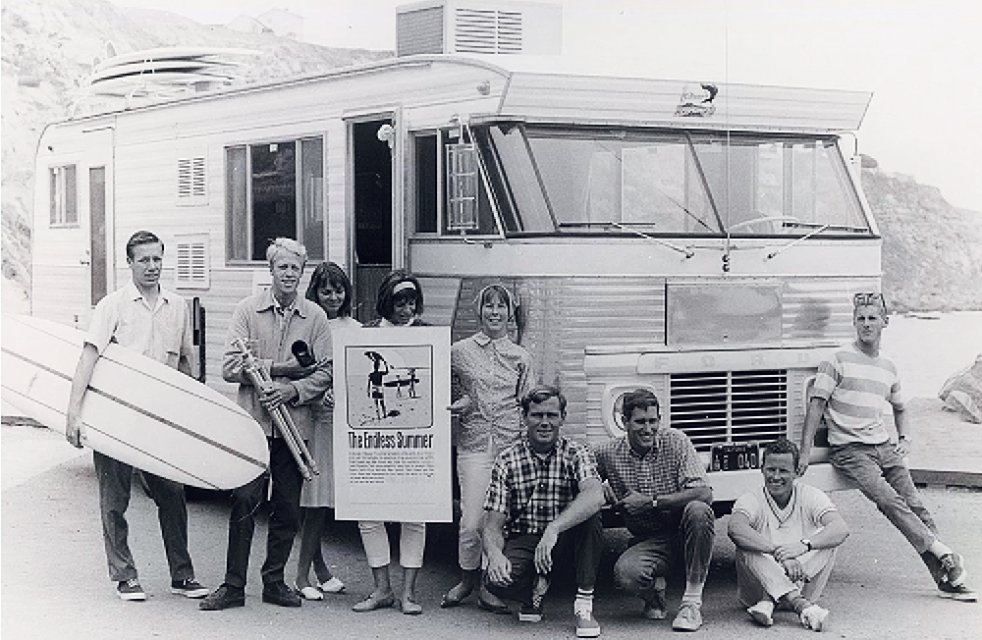

Well, the trip was about three months, but we spent a couple years shooting it and editing it, and finally reducing it to 16mm where we’d show it at local venues, and then we’d try to get it in theatres, but nobody wanted it, they weren’t interested. So we had a big struggle to finally get it released in theatres, ’cause you know, they’re just kind of going, “Well, A: the title’s stupid.” Then it’s like, “There’s not enough girls in it,” and whatever. So we ended up renting a theatre in Wichita, Kansas in the middle of the winter to prove to the suits in New York that it would draw a crowd. Well it broke the theatre record, sold out for two months. So we thought, “Well, that’ll prove it to ‘em! We can draw a crowd anywhere.” But they still weren’t buying it. It was kinda, “What do people in the midwest know? They don’t know jackshit.” So we went to New York and rented a theatre – which we’d been doing for years at our own little venues… you know renting the Hermosa Beach Auditorium – and then it played there for a year. And after a couple of weeks they started taking notice, like, “Maybe this thing will draw a crowd somewhere.”

So you’d been showing it for over a year when it finally got released properly?

Two years.

Wow.

From 64 to 66, then we blew it up to 35mm in 66 and started the theatrical release, and then I spent the next two years going to all the different towns and cities around the country to promote the movie because they’d open it one city at a time, and we’d go and meet the movie critics and promote the film. So it was another three years of being on the road a lot, going to all these different places for these openings, and it was kind of painful because you’d go to the theatre and the movie’s out of focus and the sound is bad… “Hey, what’s going on gawdamnit!?” I almost got in eight fist fights trying to get an in focus projector.

When you first toured it, before you got the theatrical release, you were narrating it live on stage, is that correct?

Yeah, I had a little recorder with the music on it, and I’d narrate ‘em all live, and to keep the music in sync with the movie, I’d drag my finger on the reel of the tape to slow it down a little bit, or wind the thing up to make it catch up, and I could pause it.

The narration is so funny, it’s the thing that really captured my imagination growing up, and still makes me laugh today, and I was wondering, did you work out the humour, the sharpness of the lines, by playing to an audience? You know, working out which jokes got laughs and which didn’t?

Yeah, exactly, people don’t realise that, but you say something and everybody groans, well you remember – don’t say that again. There’d be like a deadspot in the movie and you’d say something, and people would laugh. So it was the process of experience doing it, and also, when you’re editing, you’re thinking of what you’re going to say, of what the point of it all is. So sitting there editing for hours and days and months, you’ve got it figured out what to say. We used to change it too, if the sequence didn’t fit… we’d re-edit it, like, right in the back of the van, so by the time it got to the theatres it was pretty well worked out.

Did you ever have any bomb nights, where you’d get no laughs, and then other nights where everyone was laughing and you’d think, “I wish I could remember all the lines I said…”?

Did you ever have any bomb nights, where you’d get no laughs, and then other nights where everyone was laughing and you’d think, “I wish I could remember all the lines I said…”?

No, you remember, I probably wouldn’t remember now, but back then my mind was a little sharper. I remember we used to get some huge crowds. We showed it at Santa Monica Theatre for seven nights in a row, it’s like a 2500 seat auditorium, and it sold out every night. We went back several months later and had a re-run and it sold. For five nights, it sold out all of those. You know, what made it successful was the audience. They kept coming back, thank god. But in the early days sometimes we’d be going to some venue in Anaheim, and it was a huge place, not a theatre, like an auditorium, and there’s six people there, and I said, “I’ll give you all your money back, I’m not going to sit up here and narrate the movie to six people in a thousand seat auditorium.” Nope, they wanted to see the movie, so I went through the whole thing for six people.

That’s so good! After 50 years of this movie, I’m sure it’s been constantly brought up with you wherever you go, what’s your relationship with the movie now? When’s the last time you watched it?

I can’t hardly bear to watch the damn thing to tell you the truth because all I see is, “I didn’t really say that, did I?” I don’t know how long it’s been. I remember I went to a couple of showings where I told the audience, “Hey, I’ve already seen it, so I’m leaving.” I’d just go home and go to bed. (At this point dog jumps in his lap… and everyone laughs, then someone hands Bruce the book that is being brought out to commemorate the anniversary of Endless Summer). We’ve got this book coming out. It’s got all kinds of stuff… can you see it?

Yeah, I’ve checked it out online, did you keep everything from when you made the movie, were you scrapbooking as you went along?

Well what happened was, this kid in Spain named Manuel, as a high school project he made this book, and he sent it to Alex, the guy that does the licensing stuff, an it was amazing. He got all the pictures and stuff off the internet, this beautiful little book, and that was the inspiration for our book. This is a letter that I wrote to my mum and dad in 1963, and it says, “Trip is going fast, we just had to fill a health form for India, one of the questions was, ‘Did you have any illnesses in the past nine days?’ Robert (August) wrote down, ‘The drizzlies.’ And then it says, ‘We just left Arabia.’ I didn’t even know we went to Arabia, but I guess we did… They found all these things in the archives, letters and stuff that are included in this.

And did Dana (Brown, Bruce’s son and the filmmaker behind Step Into Liquid) do a lot of the writing?

Yeah he wrote most of the copy for the book, Robert wrote a page, Van Hamersveld (the artist behind Endless Summer’s iconic poster), Bob Bagley, then I wrote a page. Anyway, I had really very little to do with the book to tell you the truth, I just supplied the raw material, it’s got original film clips from the movie in it…

When were you making all those films over the 60s, I’d like to know if you had a favourite surfer, to watch, or to shoot, or to work with. Was there anyone who was magic for you?

Phil Edwards. The good thing about Phil was he could make bad waves look good. Whereas with surfer that wasn’t as good as him, you’d think, “That surf’s no good.” But Phil was good enough, stylish and whatever, that it was like tying up fish in a hole – if the surf wasn’t good he’d make it look better than it was.

Did you want him for Endless Summer? How did you come to working with Mike Hynson and Robert August?

They were available to go. I’m sure I talked to Phil and most people, but they couldn’t just pick up and leave for three months.

Do you have any favourite ever sequences that you have shot?

One of them in Ghana, with the locals, trying to get them to surf and this and that, that’s one of my favourites because it was totally…. we had no idea what was going on. We’d show up at the beach and there’s all the locals, and we’re saying, “Oh, well I hope they like us, this could be the end of our trip right here.” So I like that one. And of course Cape St. Francis.

Yeah, Cape St. Francis. My favourite line from that goes something like, “Think of the hundreds of years these waves must have been breaking here, but until this day no-one had ever ridden one, think of the thousands of waves that went to waste, and the waves that are going to waste, right now, at Cape St. Francis.” Uh… I obviously, didn’t do it as well as you delivered it, but I can imagine at the time people in the cinema hearing that and thinking, “Oh my goodness! We’ve gotta go.”

The thing is, the surf only lasted a couple of hours, and then the next day was no good, and so we just lucked out that we happened to get it just right at the time. And then people say, “Why didn’t you go to J-Bay?!” Well, there was no J-Bay at the time, no one really knew about J-Bay, so that’s why we didn’t go there.

There was a wave discovered just two weeks ago, I think somewhere in Africa, it’s a very similar Cape St. Francis sort of wave discovery with World Champion Mick Fanning, and there has been a lot of debate about whether they should have even shot it – did that element exist at all back in the early ‘60s?

As far as keeping a spot a secret?

Yeah.

No.

I’ve whipped through my questions, Bruce, but I’ve got one more for you. For On Any Sunday, did you go to the 1972 Academy Awards?

Yeah we got nominated for it, we didn’t win… damn commies. Anyway umm… I guess so. They might have had a separate one for the documentary guys at the time, but to tell you the truth, I don’t really remember. Did I go or not? It’s a good question (laughs), I might have to ask somebody.