The Short History Of Legropes

Share

Necessity is the mother of invention, and success is said to have many fathers. In the case of the legrope, it’s like a fertility clinic waiting room. Dads everywhere, checking their phones. First, there’s a guy called Peter Wright in Raglan, New Zealand. Somewhere in the very early 1970s, he concocted something out of nylon cord to combat the enormous down-the-line paddle that could result from a dropped takeoff at Whale Bay. Whether it was effective or not is hard to know – he didn’t patent it, and obscurity resulted.

Around the same time in the US of A, at the Malibu Invitational of 1971, young Californian Pat O’Neill was ridiculed for wearing his invention, mockingly labelled the “kook cord” – a length of surgical tubing wrapped around the wrist and affixed to the board by a suction cup. The gadget did give surfing a lasting legacy, but not the one Pat intended. His father, legendary wetsuit inventor Jack O’Neill, wore the device at Santa Cruz in 1973 and lost his eye when the board sprang back, necessitating his trademark eyepatch. (Australian Mick Asprey is another pioneer to lose an eye to a legrope – in his case when caught and flogged on the shallow coral of Reunion Island’s epic lefthander, St Leu).

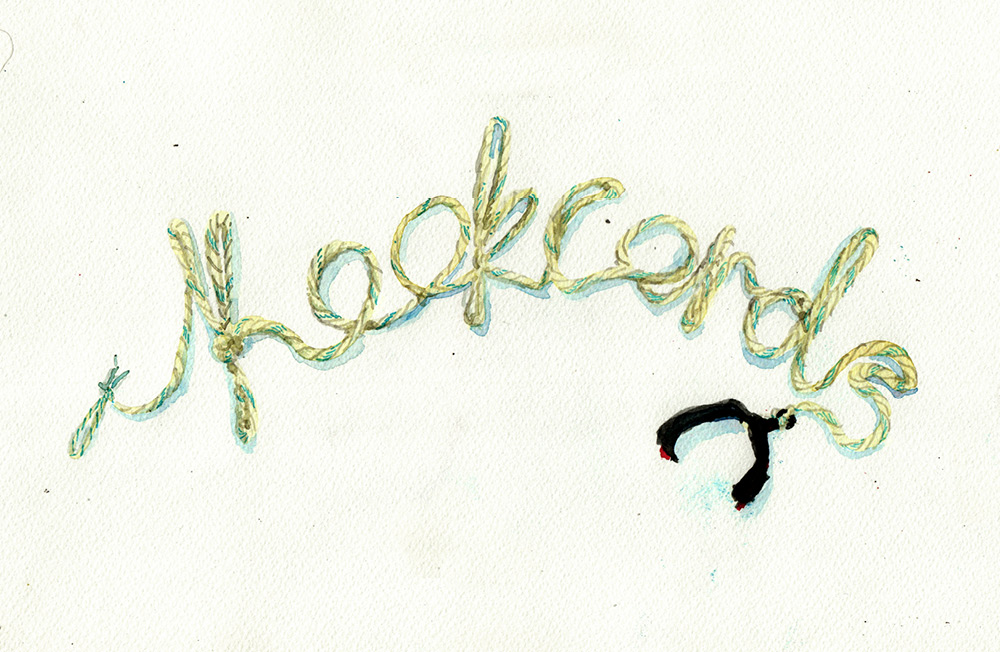

Next came a guy called Larry Block, also an Amurkan, running ads in Surfing magazine for a leash that used bungee cord instead of surgical tubing, reducing the stretch. All yours for five bucks. Next, according to the wonderful surfresearch.com.au website, the legrope “was rapidly adopted as a rope and strap (commonly a sock or handkerchief) tied to a hole in the fin. By 1974 commercial models of rope/latex tubing and velcro strap were widely available.”

But urethane was the materials breakthrough, combining strength and flexibility with reduced stretch to minimise high-speed returns. Balin were in there early, but the urethane design was patented by Australian David Hattrick in 1977. Reputedly, he’d made a prototype in 1972 while surfing Cactus, motivated no doubt by a disinclination to swim long distances over those deep, dark channels. Around 1975, his business Pipelines Legrope Co (with John Malloy) came up with a design that could be patented. According to Sue-Lynne Aldrian-Moyle’s recent book Surfing Down South, Pipelines’ legropes were handmade in a tin shed at Wyadup, among the trees of the south-west, but were good enough to win a major design award.

With reliable cords on the market, there came the years of transition: in the final of the Alan Oke on Phillip Island in 1977, officials banned the use of legropes. This magazine ran a photo of Wayne Lynch pulling into a barrel on the shallow reef at Blacks during that event, switchfoot and sans leash. But the expansion in surfing that resulted from the new invention was undeniable and based on several unrelated benefits: people were more willing to try new moves because they didn’t need to chase stray boards when they failed; fewer boards were being totalled on the rocks, so new waves became safely surfable, and the elimination of swimming meant people were simply getting more waves per session. So in the aggregate, more surfing was being done, and it was being done more experimentally.

Yet the contention around leashes has never quite dissipated. At Byron and Snapper, a decades-old debate continues to rage, as certain young bearded folk ride timber boards without legropes (presumably in pursuit of some kind of bespoke visual purity) and their boards are implicated in braining people.

The spectre of civil liability has been raised: if you choose to do something so obviously dangerous, shouldn’t you have to pay? Some US states have “leash laws” requiring surfers to don a leggie, because for every victim of legropes, every Jack O’Neill, or Mick Asprey or even Mark Foo, there must be thousands of nameless lugs out there sporting black eyes and busted noses from stray alaias bouncing through the line-up.

Legropes aren’t really that annoying – only when they form a knot that all the force on Earth will not release, or when they slip into that little valley between your fourth and fifth toes and then pull tight. Besides, they have a million incidental uses. In an absolute emergency, they’ll secure boards to your car roof or your dog to your wrist for walkies. They’ve been used as an, ahem, personal restraint (remember to agree on a safety word), and the soft neo cuffs are bloody unreal for staking your tomato plants.