GIRLS CAN’T SURF

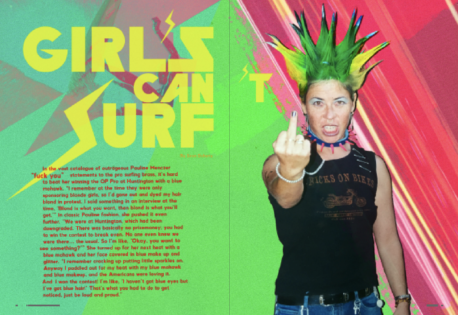

In the vast catalogue of outrageous Pauline Menczer “fuck you” statements to the pro surfing brass, it’s hard to beat her winning the OP Pro at Huntington with a blue mohawk. “I remember at the time they were only sponsoring blonde girls, so I’d gone out and dyed my hair blond in protest. I said something in an interview at the time, ‘Blond is what you want, then blond is what you’ll get.’” In classic Pauline fashion, she pushed it even further. “We were at Huntington, which had been downgraded. There was basically no prizemoney; you had to win the contest to break even. No one even knew we were there… the usual. So I’m like, ‘Okay, you want to see something?’” She turned up for her next heat with a blue mohawk and her face covered in blue make up and glitter. “I remember cracking up putting little sparkles on. Anyway I paddled out for my heat with my blue mohawk and blue makeup, and the Americans were loving it. And I won the contest! I’m like, ‘I haven’t got blue eyes but I’ve got blue hair!’ That’s what you had to do to get noticed, just be loud and proud.”

Of course, Pauline was a born exhibitionist. “I was a full-on show-off,” she recalls. “It’s the showing off that was the big driver for me. That’s why I loved the tour. That was my stage.” But over time that love affair with performing in front of a crowd became a little dark, as the women increasingly became the sideshow to the men. Wendy Botha put it this way in the film. “We had people saying the women aren’t that good and exciting to watch and people are leaving the beach when they surf. Well fuck, I’d leave the beach too if I had to watch the girls surfing one-foot onshore rubbish!” For Pauline, in time, as the women were pushed to the margins, her natural exhibitionist streak took the form of protests against a system stacked firmly in the favour of the blokes. She wasn’t alone.

The original working title of Girls Can’t Surf was The Sideshow, because next to the men that’s exactly what the women’s surfing tour became. The film opens with handycam footage of American Jorja Smith on the beach in France in the mid-‘80s. “This is where the men are surfing,” she says, pointing to a neat little peak, before swinging the camera down to a gurgling mess at the other end of the beach, “and this shitty hellhole scum-pit-of-the-ocean is where they had the women surf.”

And so it begins. Girls Can’t Surf rolls on, setting the record straight on how pro surfing left the women behind. This is not an exclusively modern phenomenon of course, but for the women in the film it was particularly galling because, as Pam Burridge puts it, at the time “the promise of pro surfing” was, for the first time, delivering. Just not for them.

The film kicks off in the early ‘80s, just as the neon lights of pro surfing start to hum. Not only was the surf industry beginning to become a giant cultural and financial engine, but the money was also rolling in from outside surfing. Coca Cola. Pert 2-in-1. Midori. Surfing was taking off. The surf industry. The contests. The pro tour. As a teenager surfer who turned pro at 15, Pam recalled the feeling at the time. “How awesome is this going to be!”

Pauline recalls the lure of pro surfing for her. “I just remember surfing at Bondi and getting better and better, then one day there was this pro event at Bondi, the first time. I’d watched some of the women in the contest and I thought, you know, I’m as good as them. Then I remember them asking me over the PA over and over, ‘Can that girl surfing in the area please move!’ I remember thinking, this is my beach! I should be in this event. Why can’t I be there?” Within a year she was.

The movie tells the origin stories of a handful of female surfing’s most pivotal figures – including Pam, Pauline, Wendy, Jodie, Lisa, Layne. Common threads emerge. Many came from broken homes, Pauline included. Her father was a cabbie who’d been murdered when Pauline was young. Her mother raised the four Menczer kids on her own, with some help from Bondi Beach. Almost all of the women featured in the movie came from beaches where they were pretty much the only girl who surfed. Surfing around Manly as a kid Pam described herself as “a boundary rider”. She didn’t have female friends who surfed and cut her hair short to blend in with the boys. As a result they all develop a fierce independence that they eventually brought with them to the tour.

Meanwhile, the guys also saw the promise of pro surfing. The idea of surfing for a living was just taking form, and while intoxicating, the reality of tour life in those early years was sobering. Most of these guys worked other jobs and were surfing event to event. As the tour grew though, they felt a sense of ownership toward it. Their efforts had built it. The tour was their domain. But despite pro surfing taking off, many of the blokes saw it as a zero sum game. Whatever gains the women made in terms of press, prizemoney, sponsorship or even surf would come at their expense… and they weren’t comfortable sharing it with anyone who couldn’t surf as well as them. It was an extension of the attitudes to women on beaches around Australia and all over the world. The line “Girls can’t surf!” was made famous in 1981’s Puberty Blues, ad-libbed by a 14-year-old Mark Occhilupo who had a cameo in the film.

“The guys were just against us all the time,” offers Pauline. “There were very few guys on our side. I had quite a few guys that I really adored – Barton, Dave Macaulay, Danny Wills – but the coldness that came from some of the others was just incredible. They didn’t want anything taken from them. In their brains, they just assumed it was all theirs. There was nothing about equality back then. It was totally, like, this is their show and how dare we come and try and take anything.” Time hasn’t been kind to the archival interviews featured in the film with guys talking about the women’s tour at the time.

With little prizemoney and sponsorship on offer, the women also found themselves scrapping with each other. The women’s tour was a small group with some overdeveloped personalities. The rivalries were colossal. Frieda versus everyone. Pam versus Wendy. Wendy versus everyone. Pauline versus Lisa. Layne versus Lisa. Everyone versus Lisa when Lisa started dating the head judge. The good natured bitchiness between the girls, recounted 30 years later in the film, lightened some pretty heavy subject matter. In the early years there wasn’t much of a distinction between the haves and have nots on the women’s tour; few of them had anything.

“The only time I’d ever do really well in a contest,“ remembers Pauline, “was when I was down to my last 200 bucks and I had to. As soon as I got down to nothing and had to win, I did. Then I’d get complacent again and lose.” Pauline never attracted any meaningful sponsorship from the surf industry, and got by running car boot sales at home, and by selling denim jeans she’d bought cheaply in America for three times the price once she got to France. She lived in her van back at home, and shared rooms on the road. “Everyone just bunked in with each other everywhere. My first year on tour I can remember waking up underneath Jodie’s hairy armpits. And I was like, ‘Holy billy, is this what we do?’”

The film reserves its strongest judgement for the surf industry and for the sport, which as pro surfing grew essentially became the one entity. Speaking generously, the mostly-male execs running the brands and the sport could never understand women’s surfing. A less generous take was that they didn’t want to understand it.

Over the course of a decade, including her time as world champ, Pauline barely got a bite from the surf industry. “They just always said, ‘Look, women don’t sell clothes.’ And I used to say, ‘Yes they do. I worked in a surf shop. Women buy all the clothes. They buy all the clothes for the guys and if you just made women’s clothes, they’d sell.’ I looked like a little tomboy anyway, but I didn’t want to be dressed up in boys’ clothes.” It wasn’t until Lisa Andersen turned up and made wearing boardshorts cool that the brands took notice. Women’s surf brands soon started outselling men’s. Even then, very little of this went back to the women and the tour, at least until the brands turned women’s tour events into exotic marketing exercises. The market brought about change more than the fact it was, you know, probably the right thing to do.

Pauline possessed the front to call them out. “I didn’t have the look that they wanted. They only wanted gorgeous blondes and I just thought, ‘Oh well, you can all get fucked.’” No one would ever tell her this to her straight-up, but underneath all of this there was another unspoken reason why the brands were reluctant to sponsor her.

“They knew I was gay. That’s my feeling. I never came out and it’s really hard to prove, but I knew what was going on.” In the movie, Jodie Cooper recalls her story about being outed on tour, after she left her personal diary out in a shared hotel room. Pauline tells of attitudes toward Jodie completely changing. “I used to hear so many stories about them all being nasty to Jodie when they didn’t know about me. Just going, “Don’t share a bed with her, she might hit on you,” or “Watch out, she’ll stick her tongue down your throat.” It was nonstop and I was just like, ‘Oh my God. It’s not like that.’ I was horrified. Meanwhile, I started to be really liked and people were going, “You’re so entertaining. The tour would be boring without you.” So I could never tell them I was gay. I guess me being naive, I thought they’d just like me for me. You know what I mean? But I couldn’t.” Pauline was never ‘out’ on tour, and in years when her French girlfriend, Nadege travelled around the tour with her, she was officially Pauline’s “coach”.

Pauline watched an early cut of Girls Can’t Surf at home, inviting over her neighbour, Derek Hynd, a guy who’d seen the tour from all angles. “I said to him after it finished, ‘What did you think?’ And he goes, ‘I didn’t realise it was so political.’ I just looked at him, and I said, ‘It’s not political, it’s actually just the way it was, mate. We were just living that shit all the time.’”

Watching that first cut Pauline had been nervous, not so much for anything she said in her interviews (she remains both gloriously unfiltered and unapologetic) but more that she’d supplied hours of behind the scenes footage that she’d shot while on tour. She’d handed over the tapes with no idea what was on them. “They showed that one bit of Jodie with real short hair on a balcony in France, and we were being crazy that day. We were running around in undies and smoking ciggies and just being silly, and when I saw that flash, I was like, ‘Oh, no. They’re going to show the rest!’”

For the women in the film, revisiting those years proved cathartic. They’ve all carried some kind of baggage around from those years that they’ve had to deal with. Pam went through eating disorders, drugs and drink. Wendy had the whole Playboy controversy. Jodie had physical assaults in the water. Layne battled chronic fatigue and Pauline battled chronic arthritis. All of this upwelled through the movie. When asked for the moments in the film that brought tears, Pauline replied, “Probably Jodie coming out. My family stuff. But I laughed a lot, too. Wendy fucking cracked me up. I forgot how much she was like that on tour, as well. You thought I was feisty. My God. She was next level. I called her actually and made her watch… I said to her, ‘You’ve got to watch this movie.’ I said, ‘You’re fucking hysterical!’”

All these women were formidable in their own way – they had to be – but they also survived with perspective. There’s a great story Pauline tells from her later years on tour. She was sitting on the beach in Biarritz, the surf was shitty, and she was waiting for the tide to go out so they could run her heat. She was sitting with Hawaiians, Megan Abubo and Rochelle Ballard, who were young but would in time take up Pauline’s fight for a better deal for the women on tour. They were complaining about the waves and complaining about being away from Hawaii. Pauline, who was living in a van on a diet of baguettes and cheese at the time, pointed out the French architecture. She pointed out the patisseries and cafés across the road. She pointed out they were on a beach, in France and that this was their office. “And you’re whinging about this?”

Surfing has been late to the party. It’s only been recently that it’s caught up with society to the point where this movie could be made. But things have moved quickly. The last three surfers inducted into the Australian Hall of Fame have, in order, been Pauline, Wendy and Jodie. The acknowledgement is overdue. For the women themselves, who’ve all moved on in the years since with families, careers, life, they’re looking back on those tour years with a new sense of the more-then-modest part they played in what we’re seeing today in lineups around the world.

Pauline references a scene in the film from Jeffreys Bay in 1999, where the girls refused to paddle out in waves barely breaking along the bricks, bru. They sat on the sand in protest, Pauline yelling to them all not to paddle out. “I felt so strongly about always getting thrown out in shit conditions, that I was just like, ‘Bugger it, let’s sit here and see what they do.’ I thought it was quite a cool thing to do at the time, but it’s not until you watch it on a movie years later that you go, ‘Wow. That really changed women’s surfing.’ I didn’t think that much of the things we did, but watching it again, I was like, ‘Oh, my God. Wow.’

Pauline was driving when she heard the news on the radio that the WSL had announced equal prizemoney for women, one of the first major global sports to do so. “I just could not stop crying. I was like, ‘Who can I call? Oh my God.’ I called Pam and Jodie and everyone. I was like, ‘Oh my God, have you heard? Have you heard?’ I feel really proud. Really, really proud. You talk to all of the girls, and no matter where they were or what they were doing, they all were crying when they heard the news.”

Today, Pauline drives the school bus between Brunswick Heads, Mullumbimby and Byron. As she drives she keeps an eye out for discarded treasures people have put out on the nature strip. Old habits. She’s continued to have health problems but still surfs, and Naughty Pauls is still indeed very naughty. She certainly hasn’t lost her sense of gratitude for the life surfing has given her. “People go, ‘You must be really bummed you missed out on the money and the good surf.’ And I’m like, ‘You know what? I’m not. I’m not bitter at all. I’m stoked for the girls today. I’m doing okay. I’m all right financially. It would have been nice to have millions of dollars, but everything’s all right.’ In a way wouldn’t change it. I became the character I became because I had it tough.”