Jamie Brisick Is A Surfing Writer On The Verge

Share

I can’t work out if this is the Golden Age of Surf Writing or it’s dying days.

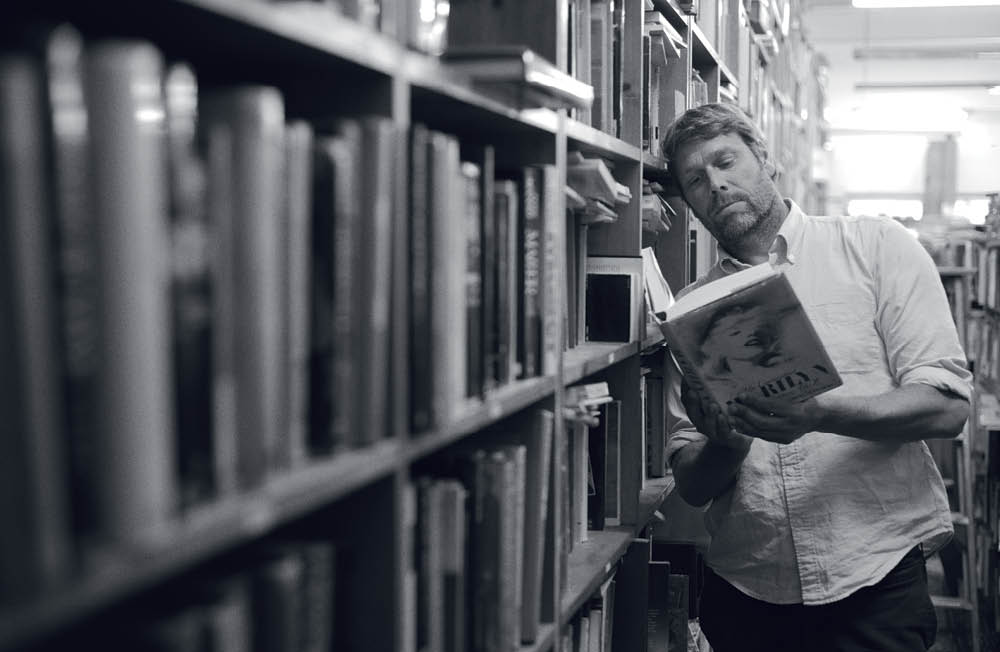

At a time when writers are being hunted to extinction and the Surf Writer’s Union can hold their annual general meeting in a phone box, a book about surfing won the Pulitzer Fucking Prize. In the midst of this confused Dali landscape stands Jamie Brisick; a man of some refinement despite being born a surfer, a man who wrote poetically about the savagery of professional surfing, a man who left surfing to live in New York and explore the mythical, purported world outside. He ventured boldly out into this civilised land, out onto the very fringes of himself, but now finds himself back in the badlands of surfing.

He’s been drawn back to surfing by the siren call of Westerly Windina, the surfing artist formerly known as Peter Drouyn, the most complex and layered and sequined biography subject any surf writer has ever had to capture faithfully in print. Only thing is that now Westerly has been reincarnated back into her previous incarnation, and it was Peter Drouyn who called Jamie and summoned him back from California to document the latest twist in his story. And this is where we find Jamie.

We could say Jamie’s one of the finest writers surfing has ever produced, but that’s running the risk of damning him with faint praise. He’s a great writer, full stop, and like all great writers he’s still evolving. He’s a writer on the verge of delivering his life’s work. He’s also a writer who is discovering the most complex character he’s ever written about might well turn out to be himself.

SW: How would you characterise the experience of writing the Drouyn book?

JB: You know, as a writer it’s been by far the most interesting story I’ve ever been involved with. I’ve never met anyone more interesting than Westerly Windina/Peter Drouyn. In Becoming Westerly I wrote something to the effect of ‘Westerly is a kind of carnival mirror, reflecting back who we are in a kind of exaggerated manner.’ And I still feel that way. The story is beyond gender and more about identity. In the beginning we thought, Okay, it’s about this man who’s become a woman, and now it’s become about a fascinating character who transcends gender and it’s about life and performance, about where the lines between the two are, and I think I’ve learned a lot about myself along the way as a result.

Looking back over the life of Peter Drouyn, his story was always more the fluidity of character than fluidity of gender.

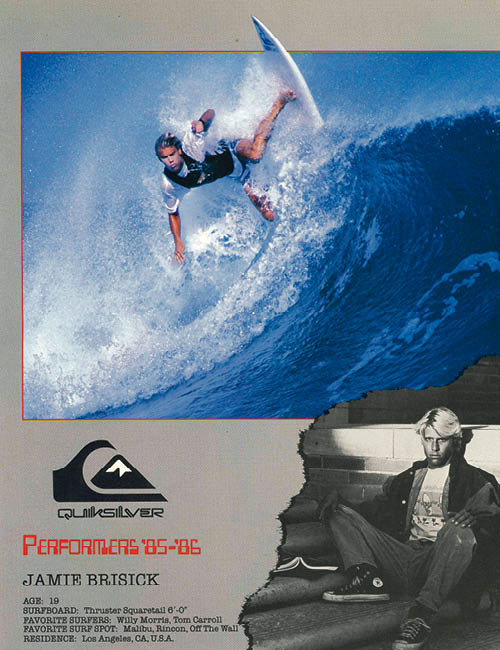

Absolutely. I guess one of the big questions is: How much are we performing? That quote by Shakespeare, “The whole world is a stage,” that’s something that has become such a big theme. I guess I thought about it a lot before. Growing up in Los Angeles and close to Hollywood and watching movies as a kid and knowing a lot of actors throughout my life, the idea of performing is something I feel close to. Bringing it back to surfing, loving pro surfing, knowing a lot of pro surfers and having been one myself, there’s the performance element of surfing itself, that idea of showmanship, but there is also the character that everyone who is in these surf magazines and surf movies create for themselves, some of them subconsciously and others more manufactured. In the end there is that question: Do we discover ourselves or do we create ourselves?

“There’s so much obsession with youth in our world and in our culture, it’s as if getting old is a bad thing and I disagree with that a hundred per cent.”

You’ve described yourself as a 50-year-old man-child… does that fluidity of character extend to yourself? Are you still evolving? Are you de-evolving?

It’s funny this conversation is kicking off on such a heavy note, and I don’t mean for it to be the way, but I’ve been grappling with these questions a lot over the last couple of years. I guess it happens in a much lighter, more subconscious manner. It’s not like every day I’m sitting here scratching my chin and furrowing my brow thinking about this stuff, but it comes up a lot. I guess it’s all developing. You know, I’m so grateful to surfing. I’ve been surfing more than I ever have in the last couple of years, and it really keeps the youthful spirit alive inside of you. There’s so much obsession with youth in our world and in our culture, it’s as if getting old is a bad thing and I disagree with that a hundred per cent. But at the same time there’s a feeling inside that’s giddy and light that we associate with youth, and I’ve been feeling a lot of that, and I’ve been getting a lot of that through surfing.

Fifty, the new 30.

50 has always seemed absolutely ancient to me. When I was 20, to meet someone who was 50, there was something depressing and over the hill about them, but being here now I feel a lightness. I still bounce around the street and imagine where I’d grind the trucks or do a little slash on my skateboard, all that stuff, but I guess I went through a period… look, I was so immersed in surfing in my teens and twenties, and when I started working for magazines and getting serious about writing I thought to myself, I’ve got to make up for lost time here. I’d spent way too much time on the beach and spent too much time living this hedonistic lifestyle, and what I need to do is get into books and get into writing. So I moved to New York and I lived there for 10 years, almost in denial of who I was and where I’d come from. I was trying to compete with people who’d gone to great colleges and spent the bulk of their years indoors, reading and writing. Now I’ve found my way back to surfing and I find myself really embracing it and I’m aware of how fortunate I’ve been to have had that in my life.

You’ve written about other people a lot, and it’s something you’ve really got to put yourself out there to do. How well do you really know anyone? What gives anyone the right to write about anyone else with any authority when they don’t know themselves… and you don’t even know yourself?

I absolutely agree. How well do any of us know ourselves? One of the things that always interested me about being a writer was the idea of being extremely empathetic, almost able to enter another person’s world, similar to what an actor does in taking on a character. To try to understand someone as deeply as you can, but maybe on some level that comes back to trying to understand yourself better too.

Is writing about yourself easier or harder than writing about someone else?

It’s hard to say. One day I’ll feel like it’s all masturbation, but I suppose going into yourself gets you out of yourself to some level, and you parse and pick it apart and try and understand your life and by doing so you get a better perspective. You almost need to become your own therapist and you almost write a profile on this other person who is actually yourself. But it’s hard to say. Over the years of writing profiles of people I have often wondered if I’m being too nice, or not saying exactly what I want to say for fear of hurting them. When writing about other people I have this battle with myself, but with memoir or personal essay I’ll happily take myself down. I’m not afraid pick myself apart and reveal my insecurities and the things we’re supposed to be ashamed of, and I feel there’s great liberation in that. I remember being younger and not having a broad range of friends and being stuck in suburban southern California and adhering to certain behavioural mores or what have you, and then watching comedians like George Carlin or Richard Pryor just absolutely rip themselves apart and admit things that are usually totally taboo, and by throwing that out there, by being shameless, they encouraged everyone else to do the same, they made it okay to talk about the murk and weirdness and perversion of humanity.

You’re always fair game for yourself.

Exactly.

Of all the people you’ve written about, who do you think you’ve got closest to understanding the essence of who they really are?

I would say Westerly. It’s been the deepest immersion in a subject I’ve ever had, and I’ve done it in long form, in a book. I wrote a 280-page book about Peter Drouyn and Westerly Windina, yet I probably had the material to write a thousand pages.

You write a lot about your childhood, and it’s infused with a warm nostalgia that leads the reader to the inevitable conclusion that this kid’s got a great life ahead of him. It was a childhood that seemed to hold so much promise. Did it deliver?

That’s a good question. I feel so fortunate for my childhood in Southern California. I came to skateboarding at a really young age, and then to surfing, and it was the ‘70s and the ‘80s and it’s funny you mention that, because I’ll often step back and go, Man, I’m getting all nostalgic for the past. What about right now? What is missing from my present? I’ve had some rough times, for sure, but the sense of what I’m feeling now is really great. But I just don’t have the perspective on it. I almost feel like looking back at yourself – and this is from someone who has spent a lot of time writing memoir – looking back at my life, it’s almost like I become someone else. It’s not even really me. I’m parsing and examining and writing stories about this character. It’s almost a kind of self-invention, but it’s not like I’m being dishonest or idealising or romanticising, but so many years have passed that my nervous system now is not the same nervous system of that person I’m writing about, so it’s no longer this visceral thing. At times it is, and you start writing something and it has emotional reference and it hits you and it’s almost like your stomach is moving with it, but then with the revisions you start looking it as a writer in a technical sense and you start and you ask, “Am I rambling? Did I say that twice?” and then it’s almost like you’re wearing a white gown in a laboratory with a microscope, picking at something and the past suddenly becomes almost cold. Writing about my youth and teens, what does that say about me right now? It’s not like I had this great childhood and now my life is shitty. If I’m lucky enough to live till I’m 70 I might be writing about being 50 in the same manner. These might be my golden years right now.

Surfing is painted as perennially young, but most of the writing about it is pointed backwards at the past.

I think about that as well and I don’t know why. Surfing is youth driven, and you open a surf mag and if you look at the faces they are young, and in a way athleticism favours that. But then the people documenting it are largely older, so there’s an almost inevitable look-back thing. If we worked for a literary journal and we were talking about the great writers in history or even the great actors, you’d find you’d be writing about Brando in his fifties, or Hemingway in his forties. We wouldn’t write about them at 20. You wouldn’t be writing about these young, trim, good looking and innocent people. You’d be writing about people with stories.

“I was hanging around people who went to Columbia and went to Harvard and Yale and I always felt like the dumbest guy in the room and almost became ashamed that I’d surfed my entire life.”

You just wrote a book about a transgender surfing savant who idolises Marilyn Monroe, a genius who drove a taxi for years and was once almost abducted by a UFO. Is the reason there is so little great surfing fiction around because the characters that exist in surfing are stranger than fiction could ever dream up? And where are those characters today?

My immediate response is that there were more great characters in the ‘60s and ‘70s than there are today. Of course, if I was 17 and paying more attention I might see more nuance today, whereas at my age and having lived through a generation in which the characters seemed larger than life, the contemporary surf landscape seems more vanilla, more bland, more homogenised, but I don’t know. While the ‘90s felt like an era where it all turned corporate and stale and the characters were stripped out of it, you had a guy like Andy Irons emerge. What an unbelievable character. You had Kelly Slater emerge. That might be happening right now and we just don’t have the window on it as we’re older and we’re not looking at it with as much wonder as a younger kid might.

But why don’t we see long form 10,000-word pieces being written about surfers today? Is it because you don’t see 10,000 words written anywhere? Is it because there’s nobody who’ll actually read 10,000 words? Or is it because there’s no one worth writing 10,000 words on? Why don’t we see 10,000 words written on someone, like, say, Dane Reynolds? That guy seems like a 10,000 words would only just scratch the surface.

Surfing has become big business. In the process of selling itself to the masses it has watered itself down. There are a lot of politics at work, a lot of dollars that stand between the clean cut, user-friendly image and the real gritty stories. Sadly that’s been the case for a long time, and I’m thinking out loud here, but I remember having this epiphany many, many years ago, when I was three or four years into working for the magazines. I remember driving away from interviewing some surfer at the time, a fairly bland character, and thinking as a writer, these guys I’m fascinated with and love to watch as surfers, what they have to offer that’s extraordinary is the surfing itself. It doesn’t always translate into conversation. They spent their years cultivating their surfing talent, so if you want to see them at their best you’d sit down and watch them surf, not sit down and listen to them talk about it. There job is the doing, not the articulating.

Is there any surfer today you’ve got a burning desire to write about?

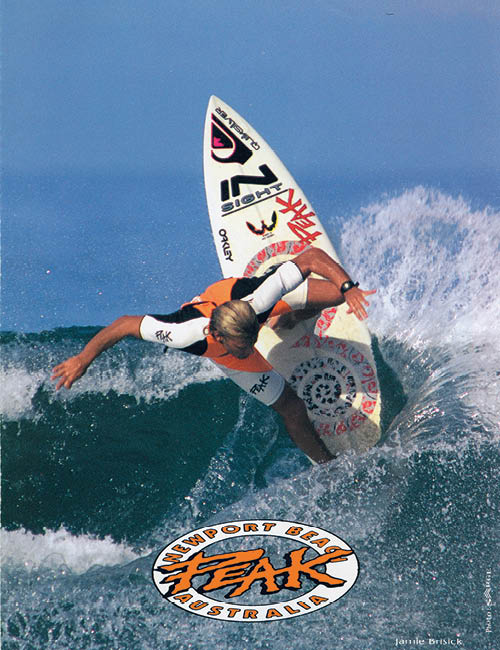

I love watching and writing about contemporary surfing but I feel a bit removed at this point. I’m more interested in people on the margins of surf culture, I guess, and I’m interested in some of the older surfers who are past their athletic prime, watching them navigate life. I was a pro surfer in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, and when I stopped doing that I was slapped in the face by reality. As Rabbit put it beautifully, I “came back to civilian life” and it seemed rough. I knew that it was going to be hard to find those highs again, and then I got interested in reading and writing and the arts, and I wanted to learn. I became curious in a way that I’d stifled as a pro surfer. Surfing is still a big part of my life, so I’m more interested in surfers my age, guys I was on tour with like Tom Carroll and Ross Clarke-Jones. I look to them with the hope to learn. What does the aging surfer do? How does he or she enjoy life? How do they keep going? How does surfing fit into their lives?

Does writing about surfing for so long – writing about any one thing I suppose – make it seem one-dimensional to the point where you’d rather write about almost anything else but surfing?

I meet a lot of people who don’t surf, and over dinner they’ll ask, “So, what do you do?” And I’ll say, “I’m a writer,”and they’ll ask, “What do you write about?” and I’ll shrug my shoulders and say, “Err, surfing,” and they’ll often say, “How cool,” but on having written about surfing for 25 years now I feel I should have more range and a bigger imagination than just this one thing. My first published pieces were for Waves and Tracks in the early ‘90s and I remember even then I wasn’t reading surf mags at the time, I was reading fiction writers, and I thought, Okay, I need to learn how to be a good writer and then I’ll expand and I’ll be writing novels and each novel will be about this different subject in this different style and I’ll have this enormous range and I’ll be this literary genius. All this hubris and this totally exaggerated sense of myself, but I remember thinking in my head, You know, by the time I’m 40 I’ve got to stop writing about surfing, I’ve got to be out of it. And I guess what I failed to realise then is that surfing is a live organism and it keeps growing. I’m 50 now and I write about a lot of things, but surfing continues to be a through line. I guess I feel burnt out on writing about high performance surfing and the surfers that dominate the contests at this point, but I’ll write about an Academy Award nominated screenwriter or actor in Los Angeles who happens to be a surfer, and we’ll have this conversation with surfing humming along in the background. And I think it’s just growing up. I look at the people I’ve written about in the last couple of years and they’re actually people I’ve dreamed of writing about. I feel like I’m being challenged in my writing… and yet there’s still surfing there.

I suppose this is a good point for Bill Finnegan to enter the conversation. I joked with Finnegan recently that he’d ruined the reputation of surf writers as the lowest form of literary life… A reputation we hadn’t worked very hard at all to achieve. You know Bill and his memoir, Barbarian Days well. How you think it changed the wider opinion of surf writing and even surfers themselves?

I met Bill Finnegan eight or nine years ago, but I’ll digress for a moment. We know surfing well and we write for some of the same magazines and it’s not a hugely lucrative career. A while back I had the realisation that if I’m going to be doing this thing that’s not going to be earning me a whole lot of money, I’m not going to sit here and wait for the editors to give me an assignment, I’m going to go and find things that interest me and that I can maybe learn from and I’m going to write about them. William Finnegan had written that piece, Playing Doc’s Games, and I read it and I thought that that was the gold standard as far as surf writing goes, and he lived in New York and I lived in New York at the time so I pitched the idea of doing an interview with him for The Surfer’s Journal. I met him and we became friends. While he was writing Barbarian Days, which has just won the Pulitzer Prize, we would have dinners every few months and he’d talk about the writing of it and he would say, “Oh, it’s going to be a disaster” or “It’s not working.” I’ve never been so close to watching an artistic process that would go on to become a massive success, seeing it from the very beginning and seeing the self doubt that even a guy of Bill’s stature experienced. It’s encouraging—it reminds me to never give up on those projects close to the heart. But to get to your question, Finnegan has raised the bar in a huge way. He’s changed the perception of surfers. He’s made us look really good.

Can you characterise the people who write about surfing?

I was talking about this with a friend recently, and it starts with a love of surfing. I think the popular writers we know, as kids they were sitting indoors reading, and I don’t think that fits the mould of most surf writers, who came to surfing first. There’s the outdoor-in-the-sunshine, barefoot, hedonistic, playing-in-the-ocean element to surfing that is the total opposite of sitting alone in a room with a book.

The two crafts are at odds.

I think most surf writers start with a love of surfing, then a love a reading, then they start writing. It’s very different to finding the books first. For a long time I thought that surfing everyday was my birth right, that I’d write around that, in my spare time. I quickly learned that writing is a full-time gig, an art form that needs 100% attention and focus. Living in New York, meeting serious artists, wanting to make serious work taught me that writing has to come first.

At what point of your career did you know you’d made it?

I don’t think I have yet.

“There’s the performance element of surfing itself, that idea of showmanship, but there is also the character that everyone who is in these surf magazines and surf movies create for themselves, some of them subconsciously and others more manufactured. At the end there is that question, do we discover ourselves or do we create ourselves?”

Well I was in the dunny at the Bird Rock bar recently and as I was taking a piss I noticed they were using one of your old Tracks stories from the ‘90s as wallpaper. I wasn’t sure however if that was a sign of whether you’d made it… or not.

Honestly, I’m not feigning modesty. I moved to New York in late 2001, just after 9/11, and I met my late wife. She was from Sao Paulo, Brazil, and she was a documentary filmmaker and we fell in love and got married and I spent a long time in New York working on this memoir about my surfing life. I should say right now it’s still yet to be published. I had a really good literary agent in New York and he worked with me on various drafts but it all just felt so off. I never felt more uncomfortable in my body. Part of it was that I wasn’t surfing anymore and part of it was that I was trying to be someone that I was not. I was hanging around people who went to Columbia and Harvard and Yale and I always felt like the dumbest guy in the room and became almost ashamed that I’d surfed my entire life. And my writing felt like I was trying to be this pseudo intellectual, it was stilted, and my voice wasn’t mine. I was out on the very edges of myself trying to be someone I wasn’t, in a bad way. I struggled with that and I went through this for a long, long time. Then in 2013 my wife died suddenly, and when that happened it was the most difficult thing I’ve ever had to deal with, but in the wake of her loss it was like all the fog and miasma that covered all the things that truly matter in my life just disappeared and I saw life in sharp relief, I saw what matters and what is important. And I thought, What a drag. I’ve spent the last seven years of my life – and the final seven years of my late wife’s life – brooding and narcissistically concerned about my book and hitching my entire identity on it. And I look back now and think, ‘What a sad waste of time.’ In the wake of her death I had the realisation, you know, just fucking enjoy life, just make it fun, don’t get so caught up in yourself—Gisela’s death released something in me. I know it’s made me a better writer. I’m more shamelessly on my path. I’m back into my voice, I’m not so concerned about external validation.

I like your Instagram posts. They make me feel like the caption is a small excerpt from a short story that actually has 500 more words on either side of it. What’s your take on social media? Are you bitter that it’s strangling the life out of long form writing?

You know, it’s funny, I remember when social media came out thinking this is just going to distract me from the unbroken attention I want to give to writing every day, and if I’m at my desk and checking my phone every minute that’s not a good thing. And then it swung the other way and I thought this is almost a rehearsal for real writing in a way. Playing with words and ideas, totally experimenting, trying to lose the self-consciousness and let these little voices just channel through you. And you know, what you said about them being parts of bigger stories is true. I’ll be working on something and I’ll find a phrase or a sentence I like and copy it and paste it in with a photo and it might be vaguely connected to the image or it might not, but I have become that much better at it. It’s about breaking away from this self-consciousness and just throwing shit out there and playing with words and characters and having fun. I’m finding play in my work. I’m experimenting a lot.

What’s the great unwritten book of your life?

I wrote this surf memoir and it deals with me on the pro tour, as a surfer, but it’s also my family story. When I was a pro surfer and I was at the height of my modest career my oldest brother died of a drug overdose and I guess I felt like things that are difficult or challenging or life altering are the things I want to write about. So I wrote this memoir about the years after my brother’s death and the actual scene where I learn of his death, my reaction to it was… Look, I loved tennis and Ivan Lendl and John McEnroe were my favourite players at the time my brother died, and I thought, What would John McEnroe or Ivan Lendl do here? They’d channel it into a victory. So in my mind I had to win the OP Pro at Huntington. At the time of his death that event was coming up a few days later and that was my defence mechanism. My way out of the pain was to focus on trying to win the contest. When my wife died my initial response was, I’ve got to write about this, and that got me through. And that’s still there. I want to write about all this beautiful and terrible stuff. That’s the story I need to tell.

I’m presuming the file lives on your computer desktop and you open it up most days and look at it and tinker with it. How do you feel about it? I presume you think about it a lot. What kind of relationship do you have with that memoir?

In the wake of my wife’s death I wrote notebook after notebook and I’ve had all these details coming back to me, but it feels like my calling now, the “love/loss memoir” is how I refer to it. I have so much written down already but I’m still a little bit frightened of it, which I think is a good thing. I think if it’s going to be the big book of my life I need to be scared of it.