LIFE WITHOUT ANDY

You probably remember exactly where you were when you heard.

I was in Borinquen, Puerto Rico, sitting by the hotel pool, chugging a Modelo when I got the text telling me Andy Irons had just died. I put the beer down slowly and drew a deep breath, a tornado of emotions, thoughts and questions roaring through my head. Hell, I thought he was still in Puerto Rico, staying just up the road. Beyond the suddenness, the twin notions of Andy and death just didn’t reconcile. Andy didn’t just die.

While Andy had lived like a rock star, surfed like a rock star, and had even riffed about the “rock star ending” in interviews, few imagined it would actually end this way, the most incandescent surfer of his generation found dead in a hotel room in Dallas, nowhere near his Hawaiian home, nowhere near his family, nowhere near anything, his heart blocked and his bloodstream about to tell a story. It was a bolt of lightning from a clear blue sky. It seemed like twisted satire. It was an unfathomably sad and tempestuous time.

In the end all I managed to reply was, “Holy shit.” The people’s champ was gone, and even as I put the phone down and took a swig of beer, even before the news radiated out from Dallas, before the world mourned, and before some uncomfortable truths were known, it was clear the world of surfing would never be the same again.

Last year, watching the Pipe Masters from a house at Off The Wall, four-year-old Axel Irons zoomed past on his skateboard, dangerously close to my toes. He was shirtless, wearing cammo shorts, and his blond mop was everywhere. He turned around, grinned toothlessly with a look I’d seen ten years ago, then zoomed back, even closer. I warned him to cool it. He laughed. It became a game. Eventually of course he ran straight over my toes, crunched them flat. As I yelled in pain he cackled with laughter and skated off around the side of the house.

Man, where did those years go?

Axel Irons had been born on December 8, 2010, a month after his father’s death, a temporal meeting between the pair surely going down somewhere, just not here. In that month, Axel’s pending arrival was a focal point for the collective sadness the surfing world was feeling. Axel would never meet Andy, which was tragic on several levels, the least of which being we’d never see the pair of them together in full flight at Pine Trees. Now that woulda been something.

Axel’s birth at least lifted spirits and allowed people to think of days ahead.

Those who wanted Andy to live on forever got their wish. Suddenly, there he was again. More importantly than that, Ax’s birth gave the Irons family something to rally around during some dark times. For while Andy might have been the people’s champ, he was first a son, a brother, a husband and an expecting father. His death was a private tragedy before it became public property, and the Irons family had to deal with it on both fronts. Hearts bled. Lyndie Irons was inconsolable. Bruce Irons was in denial, refused to believe any of it was true, and simply waited for his brother to get back from a surf trip. Andy was a magnetic soul whose passing moved strangers to tears, so think for a minute of his family. One could only imagine the heavy air inside the Irons’ Hanalei home during those first days.

Five years on and time has smoothed the road a little.

The family has found their feet again. In the year after Andy’s death, Bruce was “on a warpath to take myself out of this place”, but five years on talks calmly about making peace with his brother’s loss. Lyndie meanwhile has carried herself with quiet dignity while chasing after her son on his skateboard and running a successful bikini business. It’ll never be the same for them, but that’s the nature of loss. However they are at a point now, five years on, when they are ready to tell their story… and Andy’s. The family is working on a documentary to be released next year that will shine some light on Andy’s final years, the truth about which has remained respectfully guarded.

Officially, Andy Irons died from a blocked artery in his heart, however, the autopsy also discovered Xanax, Ambien, methadone and recent cocaine use. How much the former was attributable to the latter we’ll never know, but the autopsy results confirmed the long held rumours and, in the absence of a definitive account, left the door wide open for people to make up their own mind about what really happened to Andy Irons, what happened in the days and years beforehand that led him to room 324 of the Grand Hyatt Hotel in Grapevine, Texas.

There was only one bona fide account of Andy’s final days, and that was written for Outside magazine by surf writer, Brad Melekian. He filled in Andy’s missing hours in Miami and Dallas en route home from Puerto Rico, backfilled the piece with the story of Andy almost drinking himself to death back in 1999, and followed the story into some darker recesses between those two points in time. The story poked the beehive, and bravely broke an unwritten code within surfing that kept such stories untold. The story prompted equal measures of praise and contempt. Photographer Art Brewer had disclosed the story of Andy’s 1999 near-death drinking binge, and one outraged, confused punter went straight out and set fire to the Dick Brewer board in his garage. Melekian started writing an unauthorised biography of Andy, but five year’s on it remains unpublished, not for want of readership.

Andy’s real story of course lived with his family and close friends and they have remained silent, as is their right, while the surf media went nowhere near the truth as it intersected two taboo subjects perfectly – underground Hawaii, and drugs. The vacuum that was created however, was soon filled online, anonymously, by untruths, near-truths, the sound of grinding axes and fingers being pointed in all directions. Twitter and message boards hummed with tales of a corporate cover up, a complicit media and enabling minders. This was the first surfing story of real consequence that had broken since the primordial swamp of online forums and blogs had evolved into higher forms, and unshackled by the real-world rules that govern traditional media, they were free to riff at will about what was really happening. Most of it was pretty wild and missed the dartboard entirely, but in the climate it was understandable. Andy Irons had just died in his prime, in a hotel room. People wanted answers, and they didn’t trust the answers they were getting. The truth was in short supply, with initial press releases citing dengue fever as a likely cause. The episode was poorly managed on several fronts. People felt like they were being played.

Would Andy still be with us if someone had made his story public in the years before he died? Who knows? The world of pro surfing might be a stuffy little planet, but while rumours swirled, less was known about Andy’s problems than most would think. There were a handful of journalists working in surfing at the time – myself included I suppose – who knew enough to put something into print, but they would have been pissing into a strong breeze. There was no evidence, no one on record, no personal appetite for an exposé… and no chance of surviving in Hawaii the following winter. Most importantly though, if you knew enough to write about Andy at the time, you knew that making his story public wouldn’t have been good for him.

“Andy had died, people wanted answers and didn’t trust the answers they were getting. The truth was in short supply.”

There was tremendous soul searching going on at that time not just within the media, but with Andy’s sponsors, the sport – and of course with Andy himself – about where the line between a private struggle and the public interest was drawn. Andy himself had considered putting his story out there himself in the year before he died. In private he was an extraordinarily honest guy, a little too honest at times, but his story would have been bigger than him, it would have dragged surfing as a whole into it, hard questions would have been asked, and that didn’t sit comfortably with many around him.

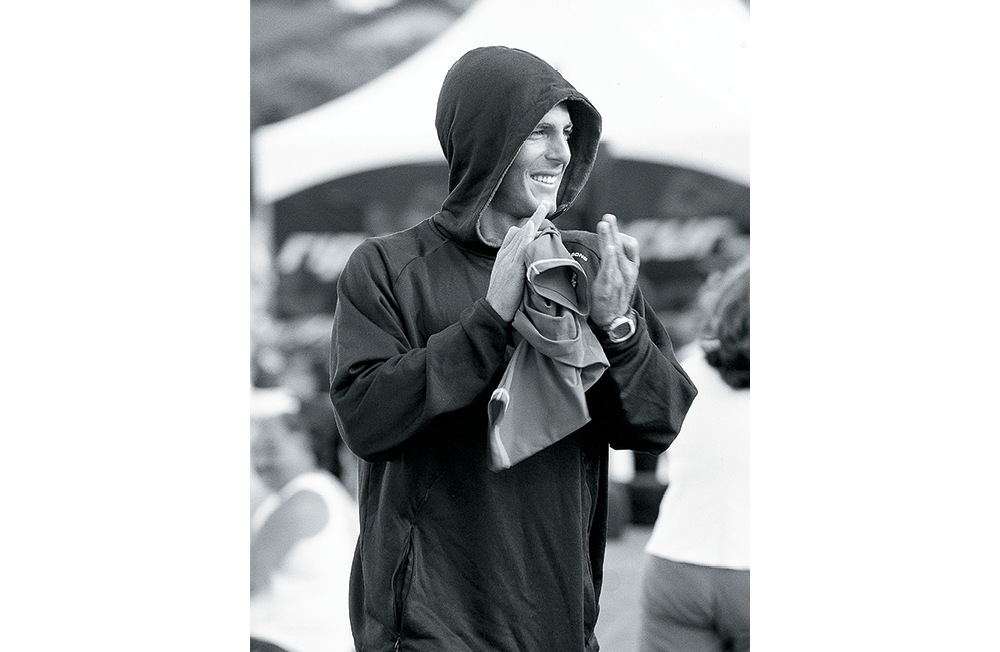

I spent time with Andy in August that year. He was staying in Angourie, in a house owned by a Billabong executive. It was, in effect, country soul rehab. He was training, he was surfing, and he was in good spirits. He talked about how he couldn’t be on Kauai right now and alluded to his personal “demons”. You sensed the clean air was giving him fresh perspective. We surfed one day at Pippy Beach, and after we surfed he spent an hour talking to the local grommets and their mums cooking the boardriders’ barbecue, holding court, asking more questions than he answered. Every one of those grommets to this day would remember the day Andy showed up at their beach, and at that point he was the last guy on earth you’d consider writing an exposé on. That stuff belonged in celebrity and politics, not in surfing. Andy was doing great. A month later I had a fight with him in San Diego and I suddenly wasn’t so sure.

On a personal level, Andy’s death held a mirror up to many of his friends. Many of them had shared Andy’s love of a good time, and for someone as vital as Andy to die in his prime made them ask hard questions of themselves. Some turned their lives around completely. Others who’d been there before came clean and told their stories as cautionary tales. I asked Occy – one of Andy’s closest friends and a guy who’d fallen off the wagon a bunch of times – whether he felt he’d been given the second chance Andy never did. His head was nodding before I’d finished the question.

Tom Carroll struggled privately for years with an addiction, and had been through rehab a few years before Andy had died. Tom’s troubles were commonly known by insiders at the time, but the story never broke in the surf press. Tom – like Andy – had a reservoir of goodwill and was allowed to deal privately with his issues. When he eventually told his own story in print last year, he acknowledged that being allowed to deal with his problems on his own terms had helped him come clean. His story, when it was told, was more powerful and cautionary than any tabloid exposé would ever have been.

But the fact that three World Champions – and counting – have wrestled with substance abuse problems at certain times will tell you less-than-subtly how endemic drugs have been to professional surfing. It’s been there since the first event of the first professional season, when a buzzed Michael Peterson won the 1976 Amco/Radio Hauraki Pro on some ragged bush weed.

Andy Irons’ death was a line in the sand.

A previous line had been drawn back in September 1992, in France, when Occy was on the beach in Hossegor, eating sand before trying to swim to China. Both he and Shane Herring had melted down, while just up the beach Kelly Slater had won his first World Title. The moment was symbolic. The era of Bacchanalian excess on tour was drawing to a close… or at least it appeared to be. While Kelly was rabidly anti-drugs and would become the poster boy for the sport, the party just moved into the shadows.

When surfing was a ragged bunch of outcasts on the fringe of society who kept to themselves, it could do as it pleased. But when it became coupled to multi million dollar businesses and professional sports, it was held to new standards. When you embrace wider society – namely their dollars and their eyeballs – you do so on their terms, and Andy’s death was a catalyst for accountability within the sport, the industry and the media. It took something as seismically tragic as losing a three-time World Champ to trigger that change.

Andy died on November 2, 2010, and within a year the ASP had introduced drug testing on tour. You can join the dots on that one yourself. The fact Andy had died during a world tour event with prescription and street drugs in his system really gave them little choice but to be dragged kicking and screaming into the 21st century. Drug testing had never been institutionalised on tour before for a mix of financial and cultural motives. No one wanted to pay for it, and no sponsoring surf company wanted to be associated with the fallout from the inevitable positive tests. And this was surfing, anyway, not the Olympic 100 metres. But five years on and pro surfing has been privatised, the new owners putting the “pro” into pro surfing, and the testing has finally come up to something approximating a global standard.

Sometimes I wonder what Andy would be doing today if he were still here. What would Andy make of pro surfing today? Of Kelly still being on tour? Of John John? How would he be surfing? What would his book have said? Andy would’ve spoken truthfully… and would’ve found he was loved even more for it.

We don’t know what Andy’s life might have looked like today, but the great tragedy was that he was only eight hours from his new life beginning. If he’d boarded that plane in Dallas, landed in Honolulu, and been picked up from the airport in Lihue by Lyndie, eight months pregnant with Axel, he would have looked over at her in the passenger seat, the angled light of the sun illuminating her face as they drove north to Hanalei, and he would have seen his future.