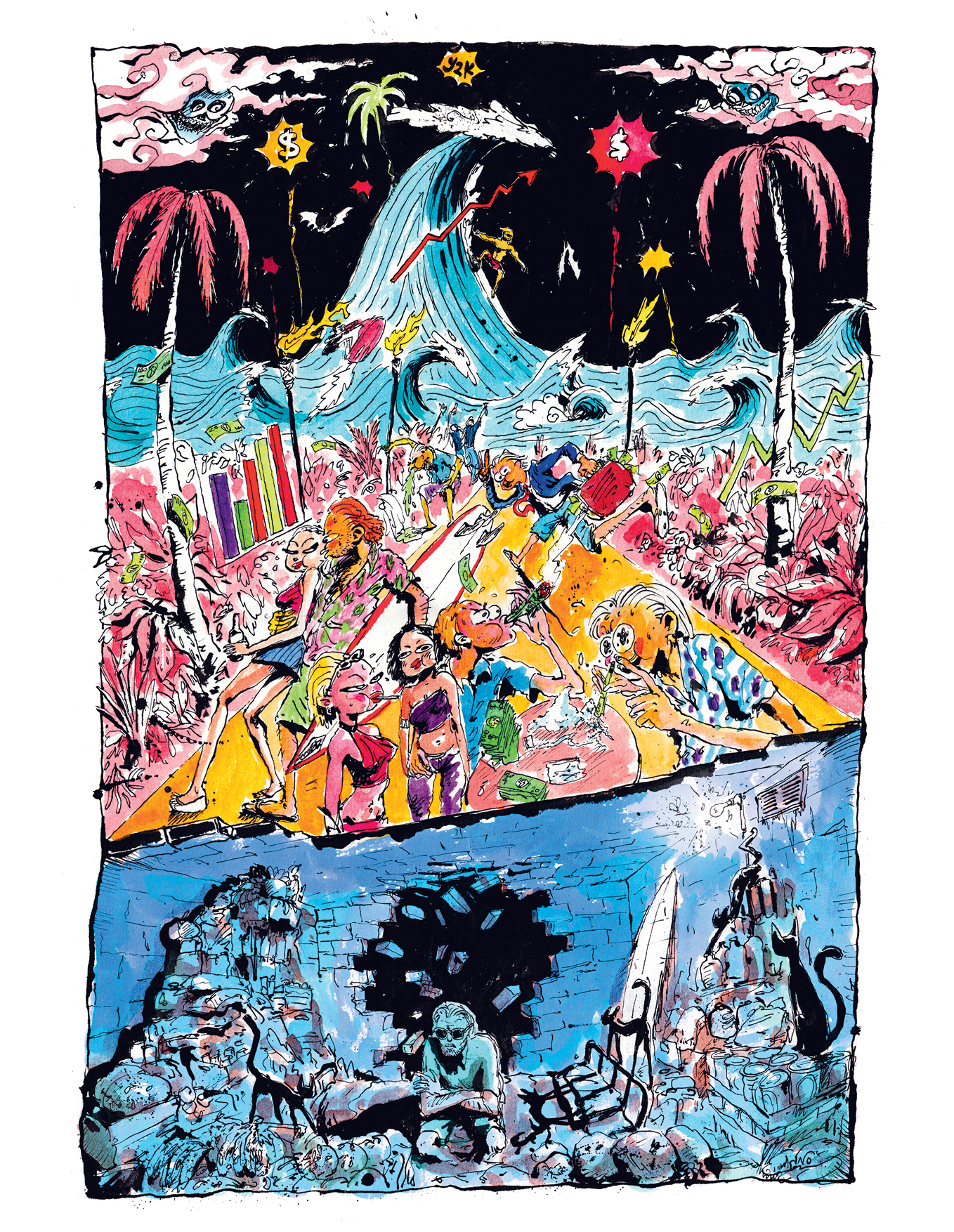

EXPOSED: MIKI DORA’S FIJIAN BUNKER

Share

On New Year’s Eve, 1999, on the stroke of midnight, I went surfing.

Flushed to the gills with fruity lexia, the finest of Doctor Lindeman’s vintages, the idea lodged itself firmly in my head that I wanted to be the first person in Australia to ride a wave in the new millennium. I paddled out in the dark at Bar Beach… but instead became the first person in the new millennium to get a giant bluebottle wrapped around their neck. I welcomed in the Year 2000 flailing on the sand in agony, blindly tearing wildly at the venomous blue tentacles covering my face, stinging my tongue, eyes and nasal cavity. As I screamed I remember hearing the sounds of midnight being counted in and champagne corks popping as the rest of the world partied like it was (no longer) 1999.

When the morning dawned and my breathing and eyesight returned, when it became clear that the Millennium Bug had been a hoax and that planes weren’t falling from the skies, I stared out to sea and was overcome with the feeling that the new millennium did indeed seem like a wondrous, parallel universe. It was an exciting time to be alive, especially if you were a surfer.

Whether it was the significance of the date or whether it was simply dumb luck, big change was going down everywhere in surfing.

In many ways surfing didn’t even look like surfing anymore, certainly not as we once knew it. Everything seemed new… except of course for Occy who’d finally become the world champ at the ripe old age of 33. But the mere concept of Occy as world champ was so wildly fantastic, his rise from the couch so improbable, that it was a sign to all that anything was possible in the next thousand years.

We were suddenly standing neck deep in the future of surfing. Boundaries were pushed. Everyone was surfing bigger, higher, faster and deeper. Everything was calibrated forward. No one dared look back. History was being written not revisited, and the hipsters of the future were too busy shredding in long boardshorts and wearing speed dealer sunnies to worry about trimming on a mid-length in an unbuttoned collared shirt. The idea of someone being more interested in the past than the future was laughable, because everywhere you looked, wild, exciting, impossible shit was going down.

Laird’s modestly christened “Millennium Wave”, surfed in Tahiti later that year, looked like a wormhole into another dimension, and even Laird himself, with his action figure physique and pink gussets seemed like a character out of a camp space film. Shipstern broke soon after and opened a portal to the darker netherworld, and then someone got the idea to boat out and surf Cortes Bank, a hundred miles in the middle of the ocean. Guys on jet skis fanned out across the oceans looking for unsurfable waves to surf. We were kicking the ocean’s arse.

The machines were taking over and even telling us where to surf as the age of forecasting was suddenly upon us. We started watching surf contests on computers, totally amazed as we sat in our lounge rooms and watched the Tahiti contest live, our dial-up connection freezing and buffering every 20 seconds but we didn’t care. We were mesmerised. Sitting on your arse in a dark room suddenly became an integral part of surfing.

The surf industry was meanwhile entering a golden age of commerce. Surfing boomed. Everyone loved surfing – people in Dubbo, people being put into the back of police cars – and surf companies were swimming in cash. Modest mum and dad surf companies were soon drawing up IPOs in preparation to go public and print money. They couldn’t believe their luck. People who didn’t even surf were willing to pay five, 10 times the market price to wear a surf shirt with a logo big enough to be seen from space.

A few hours before I’d paddled out into the surf on New Years Eve, two time zones east over on an island in Fiji, one of these large surf companies was splashing big. They’d booked the entire island, loaded the bar and hired Sublime to see in the new millennium. No expense was spared. The future couldn’t have been any brighter.

But not everyone was so optimistic.

At the far end of the island, hidden away in a windowless bunker, was Miki Dora. He wasn’t so rosy about the new millennium, so much so that he’d been stealing food from the kitchen and stockpiling it in his room in preparation for the January 1st apocalypse. He barely came out in daylight hours, and when encountered during his scuttling runs for supplies he’d mumble something about the end of the world before disappearing.

The misanthropic Dark Lord of Surf was the odd man out on the island and in many ways the odd man out in surfing. The arch nemesis of the surfing mainstream, here he was amongst a company eyeing off a billion dollars in sales, much of it to people who didn’t surf. Miki, in all his contrary glory, had been under the wing of the company for years as they paid him a retainer to surf and play tennis in France while on the run from the US taxman.

As the sun set on New Years Eve, the sole surviving member of the surfing counterculture was holed up in the bunker at the end of the island, his stockpiled food starting to turn in the tropical heat and becoming maggot infested. Miki sat there, huddled in the dark as Sublime opened with Santeria. Then as the champagne corks popped and fireworks exploded and the band counted in the new millennium, Miki lay there in the dark and closed his eyes.

Dora woke on New Years Morning in the year 2000, stuck his head outside, squinted in the white Fijian sun, surveyed a perfect South Pacific day, then promptly walked back inside and closed the door.