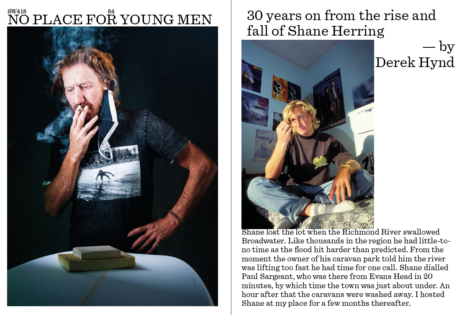

NO PLACE FOR YOUNG MEN

EXCERPT: Thirty years on from the rise and fall of Shane Herring. By Derek Hynd

Shane lost the lot when the Richmond River swallowed Broadwater. Like thousands in the region he had little-to-no time as the flood hit harder than predicted. From the moment the owner of his caravan park told him the river was lifting too fast he had time for one call. Shane dialled Paul Sargeant, who was there from Evans Head in 20 minutes, by which time the town was just about under. An hour after that the caravans were washed away. I hosted Shane at my place for a few months thereafter.

*

Not to put too fine a point on it, but by the time consumptive drunks hit 50 they’re a fair way down the road to being beaten all ends up, or stone cold bitter, or worse… stone cold. Despite gut problems, the bottle, and rough life for 25 years, Shane was the consummate gentleman – humble, hearty, level, engaging, organised, generous, honest to a fault, and quick of thought. Ask yourself how many drunks you know like that. It was offset by the fingernails. Thick, hard, starkly protruding pintails of nails. I mean, heavy duty, 10-pointed security, befitting a midnight goblin best left alone.

He threatened to have a surf. I talked him right off using a small board. I’d been with him in the water about six or seven years back. Hand eye coordination – shot. Depth of perception as swells came right to him – shot. He maybe wouldn’t recall it, but there was fear in him that day. A 9’6” Will Webber gun was laying around and I talked him into an old mantra – a gun for touch in tiny surf. Well, he picked up an empty reform from The Pass bozos and bozettes and took time to get to his feet. It was literally a Big Wednesday moment. He trimmed into a sun dropping low on the mountains and didn’t stop. For mine it was one of the great one-wave surfs. Two hundred metres, arms to the sky.

SHANE “Homage to the setting sun. Your words were ringing in my ears: ‘Don’t try to turn Shane, let it trim!’”

Riding a wave never got better than this. Stuff being best on Tour.

*

Shane Herring hit number one on the World Tour rankings 30 years ago at North Narrabeen by winning the Coke Classic. His form was close to best versions of the departing Curren and the rising Slater. He posted a baton shift and foil to the Momentum Americans. It was April 1992. A Dorothean tornado took him from podium to the overseas tour legs. Seminally, Dee Why RSL by day and night, sat fatefully timed in the hiatus between. As closed loops go, a select crew of piss drinkers spawned a monster of the id. When his feet finally hit the ground after that very first schooner on a tall stool it was the start of 1994 and rough life was the only logical calling. Pauline Menczer simply called the Herring period “darkness”.

SHANE “Ha ha, yes. From the start of 1994 I knew I was better off being a non-pro surfer.”

Such darkness wasn’t the sole domain of the Herring period. The Tour was full of it back to North Shore seasons heading into the 1970s and heading out of such seasons beyond the death of Andy Irons well into the 2010s. Whatever the role of rascals, rogues and ratbags in the downfall of Herring, it’s arguable that no lesson was learnt by anyone inside and outside of The Tour – except strangely enough by the subject of this piece. Frightfulness. Hopelessness. Pointlessness. Darkness. That no one was sent down for gross Class A drug possession over the full course of 40 years of pro surfing is but a quirk of fate that shouldn’t have come to pass. Relatively speaking, Herring was an angel next to exponentially worse examples. He merely walked the plank long in service.

A regimen of mind/body fitness fed the rise. Few knew the depth of it. Such was the curve of sparring top-ranked pros behind closed doors in training, long-term massed leg weight repetitions, and groundbreaking boards, that the celebrated Narra victory over Kelly Slater was more a warm-down than pressure test after three years hard backroom graft. Even trainer, Terry Day was out of the picture by self-design. The entire Herring repertoire was ingrained, loaded, unstoppable. For small wave, top flight arrival he hit marks in competition before Slater which put him alongside Potter’81/Curren’’82/Occhilupo’84. Despite a powerful tour top 10, Herring/Slater at North Narra was best case timing for next gen pro surfing. The moment, as it turned out, was bottomless.

*

The Troubles. Some pros would’ve been better off never having set foot on The Tour.

The Troubles. Some pros would’ve been better off never having set foot on The Tour.

There’s a moment in the following interviews when Justin Crawford talks about first impressions of Shane Herring, minutes after the Coke Classic victory. As a son of Peter Crawford, Justin held innate hindsight/insight/foresight. Justin’s thoughts amidst the instant maelstrom of celebration? “I had the feeling despite being a kid that it was already all over for him.” Tossed into his Dad’s Kombi in the North Narrabeen carpark, Justin was with Shane, the overblown 30 grand cheque and about nine other Dee Why sons. So high on endorphins was Shane that the euphoria just carried on down his throat at Dee Why RSL. Brian Langbein, aka ‘Runner One’, Dee Why’s fabled veteran gatekeeper recalls, “He drank for a week. When I caught up with him he got me maggoted. That’s a week later.”

SHANE [Smirks, nodding.]

Finally, mercifully, Shane boarded that plane to Japan. Fry pan into fire. Shane left Australian shores having staved off challenges from Slater, Hardman, Ho, Elkerton and Gerlach for the 1992 ASP World Championship, as the most the most ill-equipped Tour leader of all time.

SHANE “Yes, ill-equipped is good, I agree with that. ‘What the fuck am I doing?’

But I’m going for it anyway.’ I was equipped or so I thought but I didn’t know what I was in for.”

Not talking equipment here, although that end of it wasn’t without controversy. Sure, it’s a cliché – the real challenge was himself. Shane had been phenomenally conditioned over several seasons by Terry Day whose stable of pros and young talent at the time of Shane’s emergence around 1989 was over 40 surfers. Outsider to golden child, his distant long-term quest was victory at Narrabeen – his training ground and site of the ’92 Coke Classic. A plan beyond it, should the scenario come to pass, was to steel himself to the Day technique across the tour plateau. So guttural was the link between Terry and Shane, the latter responding to the same relentless type of rigour that Rob Rowland-Smith would famously inflict upon Mick Campbell and Danny Wills at the end of the 1990s, that Terry tapered the training then entirely terminated his role months ahead of Shane’s primary target.

SHANE “I had enough to keep me going so I kept training on my own. He taught me to train on my own.”

As a tour coach and writer I’d seen in Herring as far back as 1989, the type of small-wave form at Burleigh Heads to place him in the realm of greatness. And then the improvement, the panache, coursed through. One hell of a stage was set, with one hell of a black curtain. Ancient key of survival, modern key to sport is basic. Hunt. Kill. Relax. Bungle the one though, bungle the lot. Call it the No-Futures. The ‘away’ tour of 1992 was no place for young men. No young Australian men at least. One event, any event, any country, merely compounded the day/night/day/night six-month train.

Party trussed up as sport. Forget about this being the sole domain of a kid gone berko. It implicates institutionalised mayhem back to amateur World Titles and early North Shore pro events, 1970, 1971, 1972. In some towns The Who couldn’t have done more damage. It dips through Andy Irons and carries on, allegedly leading to an unlocked lost phone being handed into the police a few years back on the North Coast with the only identifiable shot being an ex-World Champion doing a rail. “Excuse me (name withheld). I’m looking for the owner of this phone. Can you tell me who took this photo? This is… you, isn’t it?”

Shane Herring alone and leading from the front, knowing it was no place for a young man. Administrations, sponsors, media, peers, even the Christians welded to Job’s Old Testament – barely have a leg to stand on looking back on a train wreck. Not that this devil’s playpen was limited to males in 1992. As Jeremy Byles casually observed as if par for the course, he had a ‘clubbed club’ on the go during the North Shore season that year. A young lady, title contender, was easily able to choof him under the table.

Background on the rise of Shane Herring need fall no further than to the feet of Nicholas Mark Wood. Aged 20 in 1992, same as Shane, Nick was already a five-year tour veteran racked by well-known mind and body pressures, home and away. Consistent peak delivery was impossible. Nonetheless, come ‘92 he was back in the Top 16 having put on one of the greatest ever mid-sized Sunset Beach performances to win the climactic 1991 event (and richest of the year), the Billabong Pro. Nick was easily the Tour’s most popular inside figure through his career despite introversions, seclusions, reclusions. That’s out of 200 interchanging people. Magical/hopeless, funny/sad, effusive/withdrawn, he was Shane’s harbinger. Light years ahead of Shane at 16 and tagged as a future World Champion from age eight by Rip Curl’s Doug Warbrick, Nick had fulfilled every expectation down the line to set up the run-of-runs as youngest ever Tour event winner at the 1987 Rip Curl Easter Bells Classic.

There’s a book on the Wood shockwave aged 13-to-16 but no one’s written it. Underground cracks were starting at Merewether fed by same-aged friends who couldn’t really be blamed for the nobble. Just so generically Young Australian after all. Apprehension was already there. MR’s celebrated godson, as a little boy he’d heard a boo from a person in the crowd when MR rode a wave at Newcastle’s Free Ride premiere in 1978. He was sitting with MR and a memory stuck. What transpired on Tour, post-Bells for the most famous teen surfer on the planet was catastrophic growth spurt. It obliterated his knees but on he kept. Body/mind/soul – racked carnage at 17. After 30 years from public view and aged 50, read on to get his take. But to set the stage, at one point after losing despite surfing a second blinder in as many days, Nick shut himself in a darkened room for several days. If Nick surfed a blinder despite physical trauma, no one objectively beat him. Judges could do this to pros.

Background on the rise, fall and submarining of Shane Herring is the Jeremy Byles upliftment service. His duty of care from the rustic 69 Shirley Street surf shop in Byron from 2010 to 2015, at worst fed Herro a static level. For Byles it was better later than never for an old friend. According to Shane, “My problem wasn’t going to the party. My problem was trying to stay at the party.”

SHANE ‘It was the 50 acid trips we bought from a bush source. We bought a bottle of liquid acid. Jeremy said something like, ‘Shane, you go to Woolworths and get sugar cubes. It was around 2012 when Shirley Street was open and Splendour was just up the road. We got 80 and put droplets on them. Jeremy ‘lost it’ after a week and his missus told me ‘Shane, you’re in trouble! You’ve got to eat the rest of them!’ So I pretended to eat the four or five left in the shop. Spat ‘em out in the shower. The longer The Tour went in 1992, I battled to keep up with Jeremy and Powelly”

Now, Jeremy Byles it should be known is a good man. A bit compulsive, sure, a probable legacy of The Tour. Did he achieve a thing on Tour? Well – record against Tom Curren in prime, 3-0. The Kelly Slater record against Tom Curren in prime, 0-5. In 1990, Bylesy, despite still being without any sleep, famously beat Curren at Pipe then backed up at Sunset, the latter in a four-man heat that earned him ASP Rookie of the Year in placing first, and Curren the impossible Trials-to-World-Title by placing second. Within this piece he provides nutshell reflections on perfect failure from the heights – a later bizarre loss against Herro in the 1992 Coke Classic round of 32, no better example.

It was Brett Herring though, three years Shane’s junior, who nailed every person’s life journey in an SW interview last year with the throwaway line, “It’s very stressful taking it easy.” Ask about the secret of Kelly Slater’s success and it’s the art of taking it easy, third element of the ancient method. He does it, continues to do it, via getting kills right or at worst close in a tight loss, usually at the death, savouring methods of murder in peaceful sleep. Professionally taking it easy takes a well worked set up beforehand. In 1992 Shane set out overseas with his mother in recovery from life threatening brain surgery. The hospital bill… well, the Coke winnings took care of it. Coming through for Mum was one source of ‘letting go’.

Know the feeling? Finishing work, the fun of firing up on Fridays for three nights of play? Or less common, the feeling of leaving a difficult past behind? Hitting the overseas Tour just about took the cake for Shane on an industrial scale. He could well figure he’d already done the business by the time he boarded the Qantas flight for Narita, Japan in ‘92. He’d saved his Mum’s financial bacon and recovery levels in clearing considerable debt coming out of hospital. Mates, his brother, Dee Why’s surfing generations, the extended region and just about the whole country felt degrees of elevated pride for a job incredibly well done. Few sportsmen, let alone good sons, ever earn the licence to tap such release.

The full 20,000-word story is available in Surfing World 418, at newsagents now or available here.