ROADSONG

EXCERPT: THE CHANNON-MCLEOD YEARS OF SURFING WORLD

By Sean Doherty

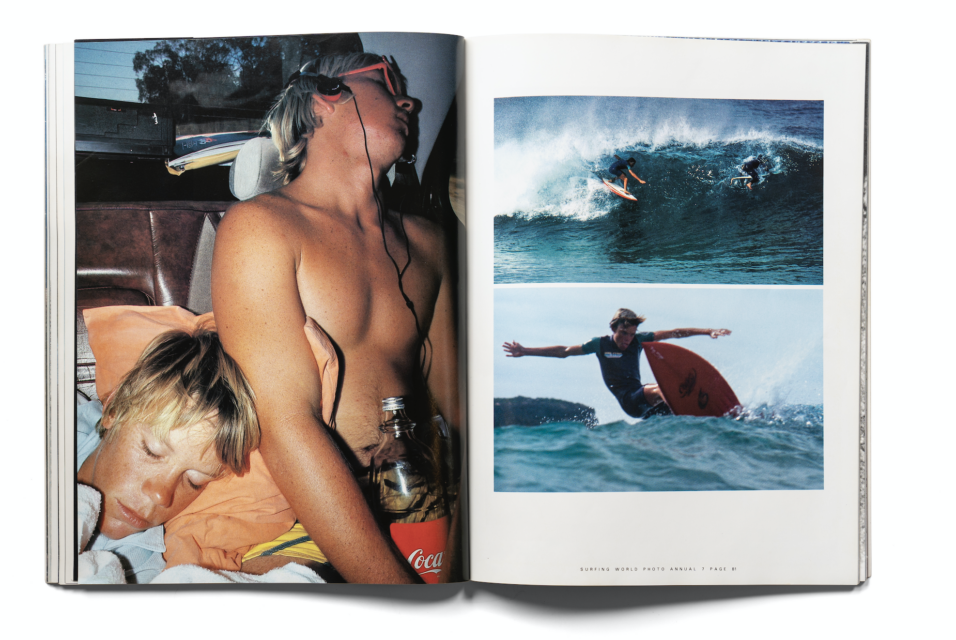

The two kids were fast asleep when the car pulled up out front.

The day before, the two Queensland teenagers had made the final of the 1982 Pepsi Pro Junior at Narrabeen and had spent the night celebrating in Sydney’s notorious Kings Cross. Kong and Chappy had only just got back to Narrabeen when Bruce and Hugh pulled up early that morning to collect them for a Surfing World road trip. Kong walked out into the morning light, rubbed his eyes and burped. The boards were tied to the roof, Kong and Chappy jumped in, and they drove south. “We passed straight out,” remembers Kong. “Next thing we wake up and we’re like, ‘Shit, we’re in Victoria!’”

It was while they were on that Surfing World trip that Kong, in a throwaway line while strutting into the Apollo Bay pub had said, “If you can’t rock ‘n’ roll don’t fucken come!” It would be quoted in the Surfing World story, which featured shots of Kong playing pinball, eating meat pies, crow-pecking Chappy and standing on an old Valiant, wearing red-and-white star trunks while drinking a king brown of Fosters. Kong was a cult hero at just 17 and Quiksilver signed him while on that trip… along with his throwaway line. Before the surf brands made stars out of surfers the magazines did, but that dynamic was quickly changing.

The surf industry was rock ‘n’ rolling. Back in ’79, Surfing World had featured a half-page colour ad from a backyard Burleigh label, Billabong. “It cost Gordon $180,” recalls Bruce. “He couldn’t afford the full page.” He soon could. Hugh remembers sharing a spaghetti dinner with Gordon the night before he flew to America with a carryall bag of Billabong samples, ready to make his fortune. Those rag trade riches however never quite trickled down to these humble, backyard surf publishers. “I just can’t believe that we never made clothing,” laments Bruce today, half laughing. “But even if we’d had a crystal ball though it wouldn’t have mattered. We never got rich but we did Surfing World because we loved it.”

Surfing World had no office. It was run between a spare room at Bruce’s and Hugh’s family home at Mona Vale, backing onto Bayview Golf Course. The master bedroom at Hugh’s became the design studio. A skylight was installed and the east-facing windows boarded up for better directional light. As the other Australian mags were gobbled up by publishing houses and moved into the city, Surfing World remained the definition of a cottage industry. Bruce and Hugh took the photos. Bruce sold the ads and wrangled the talent. Hugh handled the printing and design. Hugh’s wife, Judi looked after the accounting and subscriptions. That was it. “I was the Yin to his Yang,” says Bruce of his partnership with Hugh. “What Hugh could do, I couldn’t, and what I could do, Hugh couldn’t. There was very little crossover in the middle. We agreed on 99 per cent of everything, and when we didn’t I’d just walk away and go for a surf. And that’s how our business relationship worked for 25 years.”

Bruce describing his role simply a “nuts and bolts guy” might be selling his part in the creative process short. Bruce brought an attention to detail and craftsmanship learned under Midget. But it was the artistic swagger of Hugh McLeod that made the finished mag fizz. Everything done today on a computer, Hugh did in-studio, in-camera and inside his own head. Hugh possessed a ferocious artistic energy and skills including – but not limited to – illustration, portraiture, typography, photography and graphic design. Hugh would hand-draw story titles or bastardise Letraset. He’d splash paint like Pro Hart, immediately shooting the result with the paint still wet, a macro lens bringing it all together.

Hugh went through phases. Early eighties design was new wave and geometric. Tilted photo frames with drop shadows broke every classic surf mag rule. A hand on the page holding a photo slide broke the surfing magazine fourth wall. Hugh’s eighties colour palette was full spectrum. Colour gradients faded from purple to pink, and red to orange. Early nineties grunge eventually became more organic with textured backgrounds of brick walls, corrugated iron, pandanus trees and sand dunes. Colours became muted and earthy, outback ochres and Indian Ocean sapphires.

When the music stopped and the mag was ready, “a prayer was said and everything jetted away for printing.” Hugh laughs. “Some of it was shit of course, but some of it I quite liked.” But while most eighties surf mag design aged like milk, Hugh’s oeuvre defined the time. Colourful, bold, boundless. The cover of Ross Marshall staring out at a firing left (or was it right?) reflected in his mirrored sunglasses became arguably the most famous surf magazine cover to ever go to print. The sunglasses had been die-cut by Dai Nippon, the full lineup revealing itself on page three when the reader opened the cover.

But while the magazine dripped fluorescent ink, the subject matter remained grounded despite Australian surfers considering themselves top of the cultural totem. “Surfers thought they were King Shit at the time,” is how Hugh put it. “All the girls loved them and they’d look down on anyone from outside the beach. Whenever you’d hang at the beach there’d be a hierarchy with surfers at the top, and if you were a champion surfer? You were top of the tree. They were like gods.” The mastery of what Hugh and Bruce were able to do with Surfing World, is that they turned the gods into ordinary blokes, and the ordinary blokes into gods.

And Surfing World tapped the same thing Bob Evans had almost two decades earlier… the lure of the next headland. This was Australia and even in the eighties those next headlands were still out there. The road trip became Surfing World’s cultural trope once again. They drove through surfing heartland. Early forays under Hugh and Bruce went south to Wreck Bay or Ulladulla, or north to Noosa or Angourie. The roadside diners, service stations, pie shops and local pubs were featured as heavily as the surf, the photo essays becoming cultural snapshots of small-town, coastal Australiana.

Excerpt from SW’s 60th anniversary issue, available here.