SHE SURFS… THROUGH A SEA OF DUDES

Lauren Hill had a dream. That’s how it all started. “How trippy! I had this really vivid surfing dream and I woke up the next day and I go, ‘I don’t know what that just was, but I have to go surfing today.’ I convinced a friend to push me into some waves and it made perfect sense.”

Lauren grew up in Florida as a Blue Crush teenager, part of a mass-wave of new female surfers in the early noughties. Things were changing. Her local surf shop opened a girls’ surf store next door and Lauren got a job there. “It was called The Girl Next Door which had a weird kind of connotation, but it was a cool effort by the guy who owned the shop to make a space for women to come in and look at boards and buy swimwear.”

It was a pivotal time for women’s surf, and the first real signs of an attitude shift in how women were seen in the water… and by the surf industry. “There was a push toward ability and athleticism and actual surfing. With women like Rochelle and Layne [Ballard and Beachley] there was a focus on performance, but after the GFC there was less industry funding for anything superfluous to men’s surf culture. There was a pullback on ability and a focus again on looks to help sell the dream lifestyle to non-surfers.”

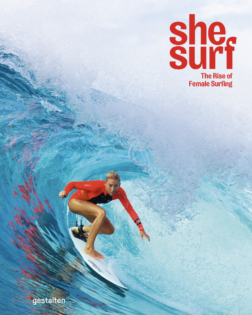

She Surf is a collection of essays, profiles, and travel pieces threading together the evolution of female surfing. The book’s subhead calls it the “Rise of Female Surfing” but Lauren points out that for the first surfers – the Hawaiians – everyone surfed, women and men, and it’s only since Western culture picked it up that female surfers have been pushed to the margins by the guys. There’s historical recognition in the book for the women who scrapped for… not even equality, just a semblance of fairness, but the book largely celebrates a kaleidoscopic vision of women’s surfing today.

It’s shifted noticeably in the past decade. Wildly in the past five. “It depends on where you are though,” offers Lauren. “Somewhere like Byron where I live, talking about gender seems ridiculous and irrelevant because there are often more women in the water than men. But if you go down the road to Lennox you’ll see the odd girl in the water, and if you talk to other women they’re like, ‘Oh man, the attitude is so intense and I feel nervous about surfing there.’ But in general the numbers of female surfers are ballooning and it’s changing lineups in really interesting ways.” Lauren laughs, “It’s not just a sea of dudes anymore.”

Asked for a moment in time to mark this change, Lauren points to the creation of prizemoney parity by the WSL last year. “As someone who hasn’t really surfed on the competitive side, the knock-on effect showing girls they can focus on their surfing without relying on sexualised surfing and marketing to make a living was huge. Just go surfing and you can make the same living as the guys.” But while the surfing of women like Steph Gilmore and Bethany Hamilton has taken women’s surfing into the mainstream, shifting the needle, the change has also happened quietly, organically, and in places far removed from established surf cultures.

She Surf travels to remote surfing corners – India, Sumatra, China – and talks with women who’ve actually found an easier path into surfing than many women in places like Australia and California. “That’s a really interesting point. Somewhere like Iran, where Easkey Britton was able to go and teach young girls how to surf, there were no questions. There were actually boys that came along and asked if surfing was something they could do too. The barriers to women going surfing have all been cultural. We make them and we can strip them back too and change them.”

The week before we talk, Tyler Wright had taken a knee during the middle of a WSL contest in support of the Black Lives Matter movement. While prompted by recent events, Lauren saw Tyler’s stand tapping – maybe subliminally – into something deeper. “There are themes that run true across the interactions I’ve had with female surfing cultures right across the world, and one of them is that a lot of women interpret their relationship with surfing to be a form of either social or environmental activism. At times it’s had to be, and surfing for women is still almost like a form of activism in itself. It’s probably being normalised a little now, but I saw Tyler’s move as a natural extension of the way lot of women across the world have felt a responsibility to speak up.”