THE THROWAHEAD VISION

A Surfing World 60th anniversary primer

By Nick Gibbs

By Nick Gibbs

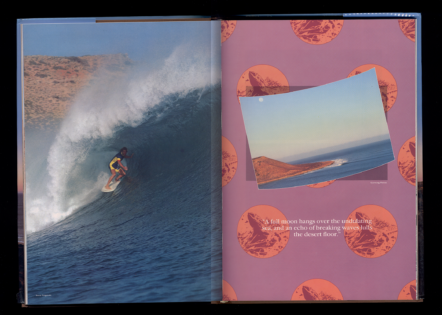

The generation of kids that grew up through the ‘70s and ‘80s could count, with near certainty, on receiving some form of hard cover book, invariably a Guinness Book of World Records or Cricket Almanac, from some adult relative, each and every Christmas. Well, Nana Gladys totally belted it out of the park the morning I unwrapped Surfing Wild Australia, its title superimposed across rippling sand, set in a textbox above the most entrancing scene I’d ever laid eyes on. A full moon setting over a desert headland. The dawn’s first rays kissing the ridgeline out to the horizon, tapering into the cobalt of the ocean, where perfect waves peeled around the tip of the point where a tiny, solitary camper sat tucked in the scrub. I retreated with the book to a quiet corner after lunch and was transported to a vast netherworld of surf and adventure, art directed into a layout of ochres, blues and greens that just screamed Australia. This was my first introduction to Surfing World.

Surfing World became a regular purchase and a more regular newsagency thumbing in the decade that followed, under the watchful curation of Hugh McLeod and Bruce Channon, and the occasional scolding from frustrated newsagents. McLeod (under the mysterious photo credit ‘Aitionn’) and Channon helmed an episodic masterpiece that transcended the glitzy starfuckery of the ‘80s and leaned hard toward a more subliminal, authentic aesthetic. I’ll be honest, I was as neon as any ‘80s grommet, and the esoteric, wistful prose that opened every issue and story was largely lost on me. But those passages created a sense of the act and setting that transcended period and place with a commitment to art and space.

They spoke of seasons and moods, of places and vibes, of mystique in a surfing landscape that otherwise sang to sponsors and stickers, urban tour stops and Sunday finals. Yet while the prose was subtle and ethereal, the action was not. The visual product was bold and ambitious, Mylar cutaway covers like the Road Song cover, single slide transparencies dropped into ochre painted backdrops, arty collages. The magazine presented the act in imagery harkening to the oft quoted inability to accurately put into words the act of surfing, knowingly and successfully tapping into the feeling of the whole deal instead.

The surfers featured were an eclectic, mixed bag that represented the totality of the surfing diaspora better than any mag at the time, each issue evenly balanced between next-big-things and local legends whose abilities would have otherwise gone completely unsung, yet have probably shaped your boards, built your house or sold you your next one in the decades since. Indigenous surfers, kneelos and grommets all got a run. Darryl Parkinson, Tony McDonagh, John Shortis, Robbie Sherwell, Brett Curotta and John Schmittenburg were underground heroes, footnotes to surfing history, yet stars in Surfing World. Fresh-cheeked Rob Bains, Luke Egans, Matt Hoys and Beau Emertons tagged along, often stealing the show.

The consistent and abiding feel was of a trip down the coast with mates. At the editorial desk, and behind the wheels of the owner’s infamous Saabs, was a constant theme of backyard exploration and underground adventure that was near genius in its simplicity. Spots were hinted at, not named. Angles focused on the action and lineup shots were a riddle. However, if you went down the street, up (or down) the coast and you saw a red Saab in a beach carpark or bush turnoff, you knew it was on. The think-you-know-where-it-is and the deliberate vagueness of the information provided gave a respectful nod-and-wink to the core crew, but for your average surfer created the illusion of endless uncharted regions to explore, of the mythical spot around the next corner. Each new issue loaded more boards and sleeping bags into cars on a Friday night than perhaps any Surfline swell event forecast ever has.

The late ‘90s handoff to Doug Lees and Reggae Ellis continued the legacy of representing the broadening church of the surfing sphere. By this time the surf world was ready to cast off the glass slipper of the new school era, ready once again for relatable boards and experiences. A more mature market, for this is what it now was, called for a counterpoint to the steady diet of high performance and industry gossip. Surfing World was never crushed under the excess of the burgeoning industry and tour, nor sucked into the various dance moves, top ten lists or obsessive Mentawai team trips of other publications. Reverential eyes looked back at the history as well as forward into a multidimensional future. Sean Doherty and Jock Serong added editorial gravitas, and the environment, women and interesting niche characters all got a good run. Vaughan Blakey matured as a savvy editor and curated an edgy yet understated cool.

And all the while, surfing was growing up. Top pros were socially engaged cultural ambassadors. Parents actively encouraged children into a surfing lifestyle. Ratbags evolved into model citizens and bought surf art and alt-quivers. Grumpy locals and grommet abuse was replaced by lineup inclusivity. People dropped the lot, loaded the van and pissed off down the coast, but the vans were nicer, the spots were more crowded and more complex responsibilities were being shirked. For many, the good ol’ days are now.

I pulled the old Surfing Wild Australia out the other day. It’ll turn 40 this year. It captures all those same feelings of the great Aussie road trip, the lust for surf and the bonds forged along the way. I can’t help but think that somehow, Channon and Macleod, and Bob Evans before them, had somehow telegraphed this vision of surfing’s future that has since come to pass, that the magazine was as much throwing ahead as reporting, that this textured, cerebral interpretation of surfing that the magazine has become was in fact their vision all along.

If so, current publishers Sean Doherty and Jon Frank, the renowned photographer whose moody, understated imagery had anchored the mags core feel, complete the circle. True to its roots, it operates from a spare room in a surf town, fitted around deadlines, surfing, real jobs and a heartfelt commitment to keeping the purity of surfing at its truest and most visceral alive. Women, tubed at Jaws, now grace covers. Articles on fallen icons are given 20,000 words of magazine space. Advertisers buy in to environmental and social messaging rather than dictate the content of mags and covers.

How has this come to pass? It might be too much to presume that the people behind this magazine have brought surfing to this place, but it might not be, either.