THE UNCOVERED MULLET

By Surf Ads

The fire came from the west. A 70 foot-high wall of flames that jumped the Pacific Highway and tore through dried-out bush and farmland, racing toward the sea. Stopping for nothing. Eucalypts exploding from sheer heat. Road signs melting.

It was November 2019, and a wave of devastating bushfires was burning across Australia’s east. The Manning Valley was quickly turning into ground zero. A ring of emergency-level fires surrounded the regional centre of Taree and nearby towns. One out-of-control blaze – the Hillville fire – bore down on the coastal hamlet of Wallabi Point. Firefighting units were scrambled in a desperate bid to save the hundreds of properties in its path. Locals huddled on the smoke-shrouded beach, their last resort from the flames.

Among the homes and rural homesteads under attack that day was one property that held a unique surfing treasure, a trove of surf memorabilia as iconic as it was irreplaceable.

Behind the home of former Hot Tuna owners Richard and Jo Meldrum sat a 20-by-10 metre shed, stacked to the roof with the brand’s entire archive, stretching back to its inception in 1969. Clothes and accessories – one item from each Hot Tuna line ever released. One-offs. Magazines. Art works. Furniture. Surfboards. For years it had been the Meldrum’s most tangible connection with the brand they had dedicated their lives to building.

But the fire didn’t care. When it reached their property the flames fed through the roof-top ventilation system and quickly engulfed the entire structure and its contents. Five decades of surf history was destroyed in a matter of minutes. The Meldrums were away. “We were on holiday,” recalls Jo, “and by the time we came back down the coast the whole area had been closed off.” While the shed went up, the house was saved – just – thanks to the heroics of friends who were on the scene.

“Would things have played out differently if you’d been there?” I ask. Jo answers without missing a beat. “Yes… Richard would have been dead.”

The stretch of coastline between Sydney and Noosa is a surfing Mecca; a thousand miles of highway bursting with history and myth. But the town of Taree, nestled somewhere near the halfway mark, barely rates a mention for surfers. Hugging the brown waters of the Manning River, on Biripi land, Taree is prime conservative country. National’s heartland. There’s farming, footy and the Giant Oyster, but not much else. Since the Pacific Highway bypassed it at the turn of the millennium the quiet agricultural town has slipped even further into obscurity. For most it is a surfing – and cultural – bypass.

But it was from these unassuming surrounds that one of the greatest forces in the Australian surfing zeitgeist was born. Hot Tuna. Operating out of a factory in downtown Taree, the Meldrums created a label that took on the world with its irreverent brilliance.

At its peak, half of the country was in a pair of iconic 8108 boardshorts. Elle McPherson wore a Hot Tuna bikini in her Sports Illustrated calendar. George Harrison and Nicole Kidman were visiting the flagship store on Oxford Street. It repped a team of surfers that could hold its own against any of the Big Three brands.

“Hot Tuna was not afraid to set itself apart from the herd,” says ‘90s surf magazine editor Tim Baker. “The other brands were caught up copying each other, so it all became bland and homogenised. Richard and Jo hated that and wanted Hot Tuna to be loose and wild and creative.” It was all that, and more. It was a juggernaut. Iconoclastic. Hedonistic. Avant-garde. The hickey on the neck of Australian surf culture. Hot Tuna rose to dizzying heights over the course of three decades.

But then came the fall. In the early 2000s, seemingly at its peak, the brand disappeared. It was vanquished from Australian shores to suffer a fate worse than death… to be sold exclusively in UK department stores, about as far from its roots as creatively and geographically possible.

So what the hell happened? How did this mum-and-dad brand from a coastal backwater momentarily take over the surfing world? And how much is too much of a good thing?

I first visit the Meldrums at their property on the outskirts of Wallabi Point on a sticky summer afternoon. A winding driveway skittles past burned eucalypts and native palms.

Though it’s been well over a year since they tore through this area, the impact of the bushfires is still in the air.

The now-retired Meldrums are ever-so-welcoming as they greet me at the door of their home but they are also protective of their brand’s legacy. The fires have left them with little else. There’s already a funny dynamic at play. They first made contact with me after Richard messaged my Instagram account, which uses an appropriated version of the iconic Hot Tuna piranha as its logo. He half-jokingly told me that if it was 20 years ago he probably would have sued me.

This is the legendary Meldrum character I had since heard so much about. The guy who would leave team surfers sweating in reception on the day of their contract renegotiation like scolded school kids awaiting the headmaster’s cane. Or show a group of potential overseas buyers visiting Hot Tuna headquarters a VHS of the bizarre Australian cult classic Bad Boy Bubby, just to see how they’d react. “A Colonel Kurtz-like figure,” is how one industry insider described him. But it seems hard to reconcile with the smiling, mop-haired surf rat standing in front of me, ironically wearing a pair of Quiksilver boardies (long story, we’ll get to that later).

Richard takes me to the site of the old shed, out behind their house. “You can see how big it was,” he says, pointing to the now-empty plot of grass. “Gone.” Tens of thousands of items – clothing, materials, memorabilia, ephemera. One nearby shipping container full of fabrics was almost saved. A smattering of burned watches and sunglass frames – some of the only items to not be incinerated completely – were salvaged. Not much to show for a lifetime’s work. Two boxes of clothing that had been brought into the house before the fires by chance are among the few keepsakes left. Back in the house with Jo, we go through the contents, which are now handled with the delicacy of a Dead Sea scroll. “This was one of the first women’s pieces Richard ever made,” says Jo, handing me a suede cowboy vest that looks like it would fit a small child. The phone number imprinted on the back is “547” which I mistake for an incomplete area code. “No, that was the actual phone number,” says Jo. “Just the three digits.” There’s a pair of 8108s. Some early noughties, bold-coloured spray jackets. “Whaddaya reckon about this one?” Richard asks me suggestively. He holds up a pair of women’s print jeans, ‘70s vintage, fitted so tight they would need the proverbial paint scraper to remove them.

“Not bad, eh?” All of a sudden it’s there. That look in his eye. That same look the group of Singaporean businessmen must have seen as the credits for Bad Boy Bubby rolled.

Jo just laughs.

Richard had always been a dreamer at school. A shit stirrer too. A lifelong surfer and Taree local, he was never one to be paying attention in class, and by his mid-teens he hit the road before the small town dug its claws in too deep. But a brief foray on the railways in Newcastle and some office work in Sydney during the late ‘60s convinced Richard the 9-to-5 life was not for him.

Always interested in art, he moved back in with his parents and started working as a leathermaker, crafting belts. He found a natural affinity with it. The gear sold well. That meant more time for surfing and partying. He started trading up and down the east coast. He ventured into clothing. His company quickly grew, with more staff being employed and a small shopfront in Taree opening.

But there was a problem. In those early days the brand was named after a favourite blues band of Richard’s… Quicksilver. It just so happened there was another small surf company by the same name trading out of Torquay. A cease and desist letter soon arrived in the mail. “We had the conversation and said you know what, this might be a good thing to change the name,” recalls Jo. “He’d go into a shop and say, ‘Hi, I’m Richard from Quicksilver’ and they’d say, ‘Ah, we just had the Quiksilver rep in here yesterday.’ So we went, this is a good thing. It was meant to be.” Richard dug back into the record collection and picked another favourite band: Hot Tuna. “Had no bloody imagination at all, did I?” Richard asks Jo.

It’s fascinating to watch the dynamic between the Meldrums. Richard, full of leftfield ideas, wisecracks, innuendo. Jo, subtly steering him back to the conversation when needed. A glimpse into how the pair – and the brand – operated so well, for so long. Jo was a Sydney girl, originally. A trained fashion designer, she came onto the scene in the late seventies, around the time of the name change, and quickly took a leading role in the brand. Romance, love and marriage followed.

Life in Taree was sweet if not slow, but the brand was busy. Richard and Jo were involved at all levels of the business: designing the ranges, hitting the road to sell directly to retailers, before racing home to actually make, pack and distribute the orders. By the early ‘80s a factory had been purchased to house the company’s burgeoning army of staff.

Though the surf industry was still in its early days, the centres of power were already forming. Sydney. The Gold Coast. Torquay. “I often wondered if we would have been as big as Billabong or Quiksilver if we had moved to the big city,” says Richard. “Because a lot of the time I would face prejudice from the retailers. ‘You’re from Taree, and you’re trying to sell me what?’” But the isolation made the brand what it was. “We had our own style right from the start,” says Jo. “We were into ethnic influences that set us off on a different tangent. We weren’t influenced by what other surf brands were doing, because we didn’t know what they were doing.”

The Meldrums and their small team were literally creating a culture from scratch. “But I also realised that making clothing isn’t all that different from building a shed,” says Richard. “You decide to take that off there, change that bit there. I remember one thing specifically, the girls printed jeans. I would alter the crotch to make them tighter and tighter. I didn’t know what I was doing but I thought, hey, if I take a little bit off there they’re gonna get tighter and tighter. And they were. They were really, really tight.” Sex sells. It might seem like a simple formula, but it was at the heart of everything Hot Tuna did. “Our printed jeans were made so that girls could go to the pub and pick men up,” adds Jo. “That was it. Like, hello? How hard is it to figure out. We were all about sex. Brazen as it was, our brand was about sex.”

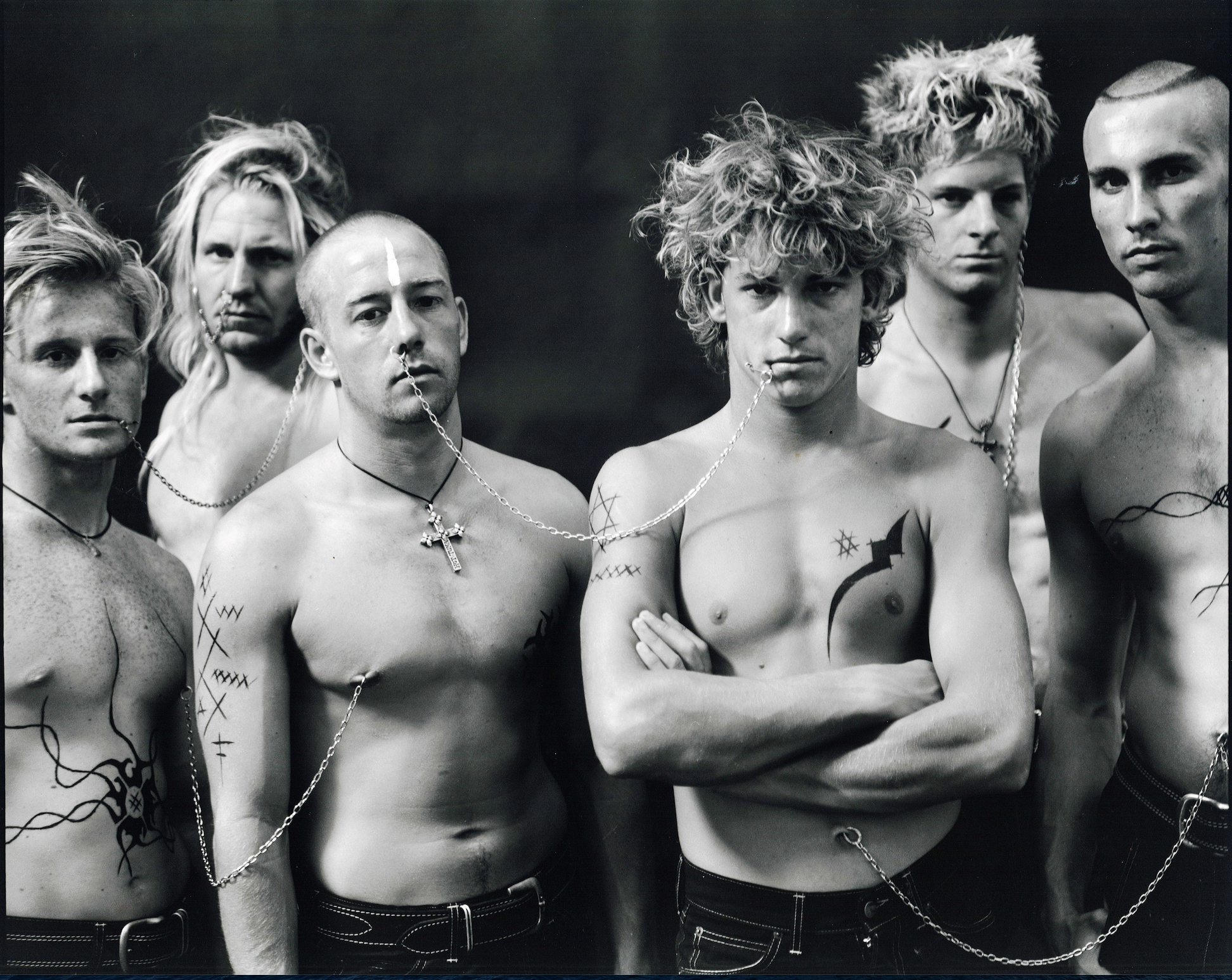

1993. Hunter Street, Newcastle Mall. Mid-week, mid-morning. The Steel City was hardly known as a centre for haute couture but a Hot Tuna photo shoot was in full swing regardless. There was the A-team of Hot Tuna surfers – Rob Bain, Richard ‘Dog’ Marsh, Beau Emerton, Richie Lovett, Neal Purchase Jnr, Mike Rommelse – a suite of professional models, photographer Graham Shearer at the helm, and Meldrum providing “creative advice” in the background.

Hot Tuna was at its peak, commercially and competitively. A crew of surfers in the Top 44, plus some of the country’s hottest up and coming talent. Top-selling merch shifting units in the tens of thousands. Shopfronts in Oxford Street, Sydney. Chapel Street, Melbourne.

And a legendary relationship with renowned fashion photographer Shearer that had already produced some of the most iconic images of the surf advertising world.

This particular shoot had started downstairs in the Newcastle Hot Tuna store, but Shearer wasn’t happy with the results. They decided to move the shoot up into the derelict area lying unused above the retail space. “At those photo shoots you would see Richard and Graham disappear into a huddle over in the corner of the room, mid-shot, and all of a sudden a new plan would be hatched,” recalls Dog Marsh. “That’s kinda how it rolled.”

“I don’t even remember what happened that day but all of a sudden we were in this insane pillow fight. There were semi-nude girls. Us nude. Upstairs at the Hot Tuna shop with the feathers all stuck to us. How the fuck did that happen? We thought we were in trouble ‘cause we were destroying this room and all the pillows, but then Richard goes, ‘Nah this is awesome! We gotta work out a way to get the feathers to stick to them!’” Honey was dutifully applied. Dog, Bainy, Rommel, Beau, Richie and Neal soon found themselves walking down Newy’s main drag, naked, covered in honey and feathers, searching for a midday schooner. The resulting photos are the stuff of legend.

“The surfers were into it,” remembers Shearer of the countless photoshoots he coordinated. “We painted them. We set them on fire. We hung them upside-down. We connected them all with nose rings. And they loved it. Because Meldrum had that ‘fuck you’ attitude there were a lot of surfers that related to it at that time. That rebel element. It was not a homogenous thing.” Shearer describes the photoshoots like assembling the ingredients for a meal but then tearing up the recipe book. “I had such freedom with Hot Tuna that I didn’t have with any other clients. You still had to get the shots but you could do anything you wanted. A lot of the best ads we did, you couldn’t even see a Hot Tuna logo in them. It was creative chaos.”

“That was the magic of those photoshoots,” agrees Dog. “They just kind of… happened. When you’re that age you wait for someone to tell you to stop. You just keep pushing shit and waiting for someone to tell us we’d crossed the red line. But they never did.” It was this ability to push the envelope and make statements that separated Hot Tuna from the other brands. Reversing gender roles in their models. Dropping heavy doses of sadomasochism and occultism into the brand motif. Opening their flagship store on the openly gay Oxford Street. Whether it was with the Advertising Standards Bureau or the increasingly conservative surf industry, the Meldrums were not scared to light a fuse under any systems of convention.

“Richard and Jo never sold out,” offers Shearer. “To their own loss. Richard kept that nucleus of his business quite tight. He could pull off that vision. The other brands were getting bigger, more corporate. They had shareholders to answer to. They had profit and loss. So they had gone much more mainstream. But with Hot Tuna there were no rules. It was all about creativity.”

It was an ethos carried into the water.

From early on the brand recruited quality surfers – both Col Smiths, Simon Anderson, Ces Wilson. They were soon joined by Dog Marsh and Rob Bain, two of the brand’s longest-serving riders, and a young Beau Emerton. Then coming into the ‘90s there was Robbie Page, Mike Rommelse, Richie Lovett, Neal Purchase Jnr. to name but a few. Even Shane Herring was on the team for a few years.

Richard led recruitment, with help from long-term team manager, Graeme Kitchen. But it wasn’t your usual cut-throat, performance-based Darwinian struggle for contracts like other brands were notorious for. “Richard didn’t run a surf team like anyone else, there’s no way,” reckons Rob Bain, who at world number two was the brand’s highest-rated surfer. Competition counted, sure, but the Meldrums were more concerned with building a culture and selecting surfers who’d embody the spirit of the brand. “Personality was more important than performance,” says Kitchen. “They needed to be good surfers, but they needed to have that flair. All of those guys had it.”

This wasn’t an approach that would work for any cookie-cutter pro. “Because it was a different brand to the others you felt like a bit of an outsider,” says Bainy. “You weren’t a number, everyone was unique in their own right. And if you look at the way Richard utilised us, on one side it was this affectionate take on us, but at the same time this really unique pisstake on the surf industry. It ruffled a lot of feathers at the time but was sort of brilliant when you think about it.”

These were larger than life characters, in and out of the water. But somehow, the pieces all fit. “I was a huge fan of every person on that team,” says Dog. “We all got on really well – we really enjoyed each other’s company, had heaps of fun together. Never a bad vibe in anything we did as a group, which I can’t say the same for with some of the other brands I’ve ridden for over the years. Richard and Jo helped facilitate that with their attitude – not putting pressure on us to perform and wanting to make sure we were good people first and foremost.”

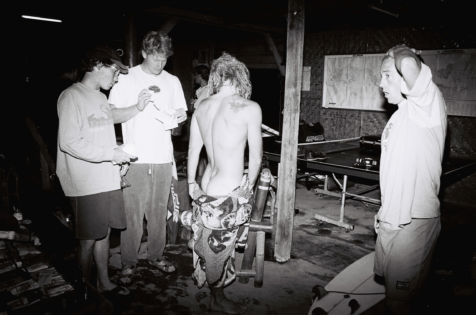

It was on a trip to G-Land to shoot for the HT team video, Lusurfer Rising that the closeness of the group would be tested in some of the heaviest circumstances imaginable.

There was Bainy, Richie Lovett, Shane Herring, Dog Marsh. Peter “Bosko” Boskovich came along, shooting stills while Monty Webber took on the filming. Neal Purchase Jnr was meant to be on the trip but pulled out just before boarding the ferry from Bali. “There was something that came to him – a sense or a feeling – prior to going across that warned him not to do it,” recalls Bainy. “He spoke to his girl at the time, she got a bad vibe too. He was there in Bali with us but when it came time to leave he just went, ‘I don’t feel good about it. I don’t want to do it.’ So he didn’t come.”

The team arrived at G-Land in high spirits. For most, it was their first trip to the legendary Javanese break and a respite from the Kuta party vortex they’d just escaped. The serene jungle setting of Bobby’s and the promise of endless tubes was enticing. The presence of Simon Law and a few of the Kuta Lines crew sweetened the deal.

But the peace was short lived. On their first night in camp a tsunami, triggered by a nearby deep water earthquake, focused in on Grajagan Bay and funnelled down the reef. It hit right on 2am while most of the camp was asleep. Those few who were still awake said the oncoming noise rose deep from within the jungle itself, like an airliner taking off. The surge hit from all angles, with the power of the impact depending on where in the camp your hut was situated. “It must have been massive,” recounts Bainy. “It had to be. Just this swirling mass of energy.” Richie Lovett later compared it to being hit by a train.

Bainy, who had chosen to stay in his own room close to the bar, awoke to find himself trapped underwater. “My initial thought was that it was a tiger. I couldn’t move, I was caught up in my mattress, rolled up in my mosquito net, with the roof of the hut all on top of me. Not knowing any of that at the time all I knew was that I was pinned, I was in blackness, I couldn’t get up, and something was on me.”

Then Bainy realised he was underwater. “I still had no idea what was going on but I knew I had to hold my breath. I think there was some sort of air pocket there in amongst that turbulence, and I just held my breath until it passed.” The first wave was over in a matter of minutes but the reality of the situation soon hit. “I’ll never forget Monty screaming at me, ‘Get out, get out, there’s another one coming!’ I was shell shocked and didn’t think about a second wave. But Monty reckoned this thing was coming back and we were gonna die.”

There was nowhere safe. “There was no high ground. We just moved back, back inland. Hoped there wasn’t another one behind it.”

The rest of the crew had been washed hundreds of metres into the jungle. They found each other in the darkness, screaming, and made their way back to the camp, which became the rally point. There were broken bones, punctured ribs and other injuries. But somehow, everybody in the camp survived. They were lucky. More than 200 locals from nearby villages tragically did not.

Richie and Dog had been dragged through the jungle and had suffered cuts and scratches. “They were really both in shock,” recalls Bainy. “Their cuts got infected and blew up pretty quickly, so they had to hike those guys out through the jungle and get them on a flight home.” Bainy and the rest of the crew stayed another few nights until it was safe to leave. He slept in a tent with one hand on his Swiss army knife, ready to free himself if trapped again. “I reckon within half an hour of the tsunami happening the locals were making offerings to the gods,” remembers Bainy. “All of them burning and offering. They were sobbing. It was incredible. Very powerful. And to see that connection again when I returned 25 years later with my son, that was quite moving.”

Bainy now refers to the group as the Tsunami Brothers. “As a team it brought us closer together again, for sure. Because anyone who experiences that sort of thing, there’s a bond there that’s pretty deep. When you think you’re gonna die… Richie and Dog screaming out for each other in the dark, Herro screaming his lungs out for Bosko, all in pitch black. Those things don’t go. They sit with you.”

To chart Hot Tuna’s ascendancy is to tell the story of the surf industry writ large. A backyard brand there at the start of it all, before a meteoric rise through the ‘80s and ‘90s. At its height the company was exporting to the UK, Europe, Asia and America. Products were being proudly shipped directly from the Taree factory. The 8108 was one of the strongest ever selling items in Australian surf retail. In one year alone a staggering 40 kilometres of charcoal-coloured fabric was ordered to keep up with product demand. The expansion couldn’t go on forever, though. There was always going to be a crash, but when it came it came from an unlikely place.

The Hot Tuna piranha was epochal. The most distinct surf logo in Australia at the time. Any merchandise bearing it sold like hot cakes. But by the late ‘90s the Meldrums were growing tired of the design. It marketed well, but by just blindly stamping the label over everything the brand risked becoming a parody of itself. “I could see some labels had kept on pushing their favourite logos and eventually it bit them on the arse,” recalls Richard. “I learned from that. People needed something new. We needed to evolve.”

It was a risky move. Surf retail was undergoing a dramatic shift. The small independents who the Meldrums had worked with for so long were drying up, to be replaced by chain stores operating in giant shopping centres. “Surfwear had gone off the boil,” says Jo. “You had lost that little surf store on the corner of the street. They had all sold out or purchased each other. They were in big Westfields and were only focusing on pushing down margins to pay their rent.”

The buyers were, to use the modern corporate vernacular, risk averse. They just wanted the piranha and turned their nose up at any of the more creative or forward thinking designs Hot Tuna were pushing. Ultimately, the Meldrums chose creativity over commercial success. “I believe we were getting to a point where we were becoming too commercial,” says Richard. “We felt it was too dangerous to keep on using the piranha as much as we did.” They dropped the piranha from their range.

It was the ultimate ‘fuck you’ to the surf industry, but the retailers were right – financially, at least. “By the early 2000s it’s a fact that our sales were not as good as they had been,” recalls Jo. For a long time the Meldrums had held off from moving their manufacturing base overseas, but the price of staying local was becoming too high. Plus, after 25 years of nonstop progression and activity, the frenetic pace of running the company had begun to take its toll. “By the time we had someone approach us and want to buy it for a fair price, we were ready.”

In 2002 an Australian company purchased the brand. Grand promises were made regarding the Meldrums’ ongoing involvement and creative input. “We were prepared to work with them, design for them,” says Jo, “but as soon as it was theirs they flipped and told us that the piranha was going to be on everything.” The company brought in ‘talent’ from the US that had restructured other brands. They used a generic approach to maximise profits, to play to the safe space. Heavy branding. No creativity. It was all straight from the corporate takeover handbook. Before long the brand was on-sold again to a UK department store conglomerate, where it still resides today.

There were no regrets on the sale, business-wise. It happened at the right time. But to see the brand lose its creative drive – and ultimately its very soul – hurt. Hot Tuna’s history, for the Meldrums at least, was consigned to the shed.

What is it that draws us to certain movements, figures, times in surfing? There’s an element of ‘the good old days.’ Nostalgia is a hell of a drug, sure.

But it’s more than that. Surfing at its heart – or at least, its modern interpretation – is as absurd as it is beautiful. The most glorious way you could ever choose to waste your time on earth. But if you’re taking it too seriously, you’re missing the point. It’s the unspoken bond that binds all of surfing’s antiheroes. A shared knowledge. The whole game is cosmic pisstake. Hot Tuna – the independent, irreverent, artistically driven brand – got it. All the good ones do. What the Meldrums and their team didn’t realise, though, was the legacy they’d leave.

The ads. The fashion. The free-wheeling surf team. Hot Tuna’s ability to capture the subverted, sublime side of surfing shaped how surfers saw themselves. It was reflective of themselves. By doing fun shit for the hell of it, and by doing it so damned well, with passion, the brand helped build a culture. That’s currency that can’t be bought or sold or stored in a shed. And it can only be appreciated through the passing of time. “Brands like Hot Tuna and Mambo represent a moment in history and you can’t ever really recapture that,” says Tim Baker. “There’s a lot of shit talked about branding and marketing but those guys really did create something unique and original.” It’s a perspective sorely missing from many areas of surfing today and it’s a truth that burns brighter than any fire. The Hot Tuna shed might be gone, but its spirit lives on. It just reveals itself in different places, if you’ll look.

Back on the Meldrum’s property, the recent rains have seen a crazy explosion of greenery. Everywhere in the landscape there are shoots of regrowth emerging. I’m with Richard and Jo, going through a pile of old ads and photos to use for this article. “Do you reckon we could start the brand again?” asks Richard as he holds up a black and white picture of Dog Marsh, hanging upside down from the ceiling, chains wrapped around his legs. “Especially now with the fires and everything. I was thinking we could call it, ‘Fuckin’ Hot Tuna’.”