‘Broken’ By Jon Frank Is All The Motivation You Need

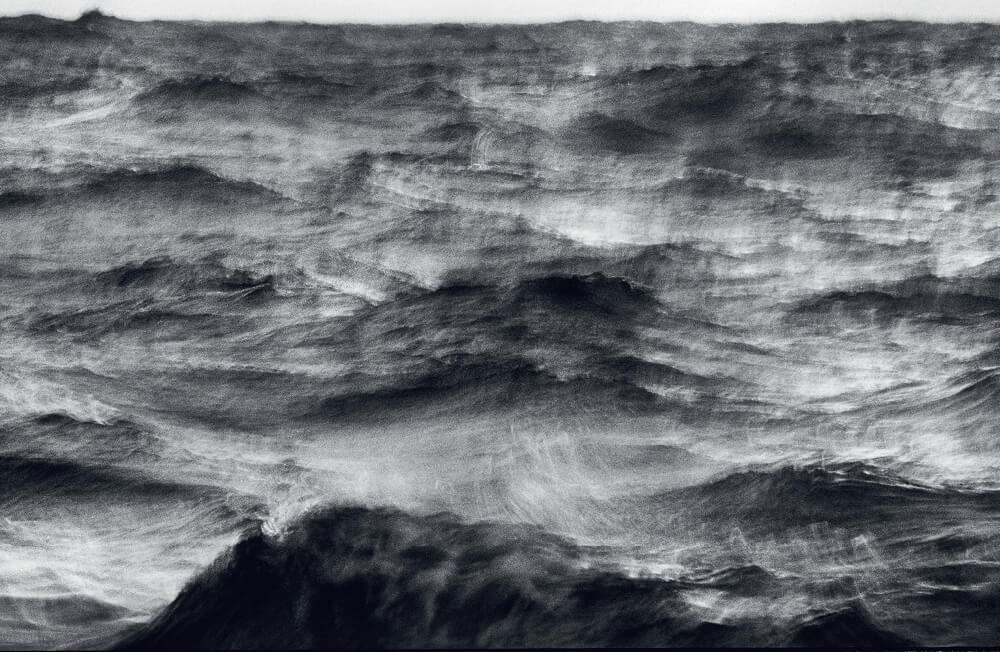

On the eve of releasing a new book of Ocean portraiture, Surfing World’s Senior Photographer Jon Frank reflects on his life’s journey shooting the sea…

SW: What kind of child were you?

JF: Sean, if you asked my mother that question she’d tell you I was a precociously intelligent, cherubic gift that the midwives said had been touched by God and was loved by all. Take from that what you will. I do remember learning Latin at the age of seven, the result of briefly attending an expensive private school in London. Whenever I recall that school now anecdotally, I refer to it as Eton, except of course it wasn’t Eton, it was Eton’s bastard third cousin. And a fat lot of good it did me. When I was born my dad had piles of money, but through the ‘70s he lost it all and that’s why we ended up moving to Australia in 1981. He was flat broke. But for one year there I was at a private school where we wrote Latin verbs with fountain pens dipped in ink. I’m not kidding, it was very Dickensian. Lots of dark wooden walls and frightening teachers who just might have included sodomising livestock on their list of fun things to do during holidays.

Do you still write with a fountain pen today?

From memory it was annoying, ink everywhere. I was a smart kid but I peaked early. Within six months of emigrating to Australia I was placed in what they called an ‘opportunity class’ which was an experimental stream for the brightest kids. Those were the best two school years I had, but the wheels fell off well and truly once I started high school. I took up surfing and after a decade or so of being a surfer and not really applying myself to anything academic, I’d lost my edge. It’s been a degenerative decline ever since and thanks to aging and alcohol the curve seems to be accelerating.

Did you have an uncommon artistic eye as a child?

No, I don’t think so. I did love listening to music. When I was very young I listened to a lot of classical. I’m talking from the age of three or four. Mum gave me this old radio and she reckons I tuned it to a classical music station and would happily listen for hours at a time. That was around the time she was advised by a child psychologist to use a straitjacket to keep me restrained at night rather than have me launching myself out of the cot. I was ending up black and blue and in our neighbour’s eyes was a victim of domestic violence so she did what was needed to save face I suppose. When I was eight years old I found a vintage reel-to-reel tape recorder at a garage sale and it came with these big reels of tape. The music was big band jazz from the 1920s and I used to listen to that quite a lot. So rather than having an artistic eye, I may have had an artistic ear. I think my eye developed when I got a job at Video Ezy at fourteen. One perk of working there, beyond the pay of $3.15 an hour, was being able to take home as many weekly videos as I wanted for free. The weekly ones were all the old classics so I watched hundreds of films of all genres in the three years I was there, which now that I think about it was a pretty great visual education.

What pop culture did you grow up with?

I was in Australia in the 1980s and the first gig I ever went to was Painters and Dockers and Lime Spiders at the Sutherland Entertainment Centre blue-light disco. We skolled hip-flasks of cheap bourbon before going in. I liked Midnight Oil and the Divinyls but there was also this person in there my mates didn’t know that much about, reading adult books, not that kind of adult book although those featured as well and listening to music passed down to me from my older brother. The Specials, Echo & the Bunnymen, The Beat and bands like that.

How did that go down in Cronulla?

I learned not to share too much because I got pretty badly bullied for a while there. When I came out from England at age 10 I just didn’t fit in. Everything was alien. It was like being dropped into the set of Puberty Blues from the set of Mary Poppins. I have vivid memories of my Dad driving down the Cronulla main drag, when you could still drive down it, with me in the back seat, nose pressed to the window. We must have only been in the country for a few days and just seeing giggling girls walking around in crochet bikinis and all these godlike bronzed surfers was a shock. I didn’t know what the heck was going on. It took me a long time to figure it out.

Cronulla at that point would have been quite a cultural baptism.

Unbelievable. I’d grown up in London in some upper-class burb that never saw the sun and I spent most of my time indoors, so to land in this place where the light was so intense and everything was bright and subtropical… and then there was this ocean! When we landed in Australia, well, the first night we went to my brother’s place but the next day he rented an apartment right on The Esplanade at Cronulla looking straight out at Shark Island. It’s still there today, it’s called Rugby, this big block with an epic view of the Island, and that place predicted to a large extent how my life would play out. I remember looking out to sea and there must have been waves breaking, but in my English brain I didn’t understand what I was looking at.

You might as well have been on Mars.

I could have been looking at anything. I didn’t know what waves were.

When did it twig?

I really don’t know. We stayed in that unit for a month or so and that whole time I was gazing at my future without knowing it. It’s difficult to remember just exactly how it felt not to know about waves because the ocean has been such a huge part of my life.

What came first, the love of water or the love of photography?

Water. I was a surfer long before I was a photographer. I didn’t pick up a camera until I was nineteen. I dropped out of school early and did some odd jobs, some shitty night shift jobs, and I went on the dole for a while and was just surfing all day. I was surfing by myself quite a lot because my mates were all going to uni.

The role of the Cronulla reefs in forging your career?

They were everything. I never used to surf the beaches, I’d just surf all the reef breaks and Cronulla is a special place like that. It’s got a bunch of classy waves, quite a lot of them, and they all work in different conditions, different winds and swells. If you were growing up on the beach breaks you weren’t seeing the same things visually and it wasn’t as interesting as if you were paddling out to these hollow, dramatic rock shelves doing all these complicated things to the dark water.

You don’t get that at The Alley.

No, you don’t, and you don’t get it anywhere on the beach and it was absolutely another one of those things where I was out there surfing and witnessing light and water performing these remarkable feats. I also loved surfing magazines. A few years earlier, a school friend had given me a whole stack of Surfing World magazines from the ‘70s that his cousin had given him. He wasn’t a surfer, he was into The Cure and he said, “Do you want these?” and I took them home and that was a huge education for me. As a kid, you pore over those things and read them over and over. I had a stack up to my knee. Still got them actually.

You’re the cat lady of surfing magazines?

I’m trying to be Zen and live with nothing but for some reason I’ve kept every one of those old magazines. I’ve moved so many times and they’re a major pain in the arse but they’re still here, all torn and dog-eared.

Tell me the story of the first roll of empty waves you photographed…

I’d bought a camera inspired by those old surf magazines and decided I’d start taking pictures. The first roll of film I ever shot was down the south coast, on a Nikonos, and it was of my old mate Sparky. We went and surfed this out of the way place that wasn’t a known break and still isn’t as far as I know. I found the slide the other day, of a perfect looking wave with my mate paddling into it. That was the first roll of film I shot in the water. I was taking pictures of surfing, but even then, I remember being just as interested in the water and the waves themselves. After that, I’d take pictures of waves because half the time I’d be out somewhere by myself. I used to surf Voodoo by myself or with Brett, a knee boarder who’d paddle out early, a real charger, and he and I surfed out there a lot. This was before surf reports so you’d drive over the hill there at Greenhills and not know what to expect and – bang! – six-eight foot lines from the south with a northwest wind and you spin the car around and head straight out to Voodoo and no matter how early I was, there was always an old Holden already there parked on the dirt track belonging to Brett. He and I would surf, just the two of us trading waves, sometimes for hours. Other times I’d be out at Suck Rock or one of these little shallow reefs and come in and grab the camera and swim out and photograph waves because there was no one surfing.

Is shooting waves on your own a product of your artistic leanings or simply a product of your misanthropic, anti-social nature?

Surfing for me was never going to Elouera dunnies or The Alley and surfing with a bunch of other people. Why would I do that when I could go out to that distant headland and there’d be hardly anyone out? And if I could surf with a friend then it was happy days, but most of the time no one was around so I’d go alone. My photography followed down that same path. I’d go and shoot Shark Island if it was on, which was always busy, so I’d take pictures of surfing and bodyboarding out there, but generally I’d photograph wherever I was surfing.

You’ve positioned yourself almost as the arch contrarian of surf photography. Shooting empty waves wasn’t even really a thing back then, and Litmus was the ultimate contrary statement. You’ve made a career out of zigging when they zag.

That may be true in part, but I’ve done a bit of both because I’ve also worked within the surf industry. There was a time I wasn’t sure which way I was going to go. It was after I’d made Litmus with Kidman and I remember deciding I wanted to work with the best surfers, and that was again coming from Bruce and Hugh who with Surfing World always had the best surfers. I was still interested in photographing surfing at the time and I’d sneak my own work in around that, but what it did was allow me to travel to some really exotic places and do a lot of exploration. I’d get to work with the best surfers, but also travel, which was an ambition of mine. I was inspired by Ted Grambeau who was living this seemingly decadent and nomadic life on the road. Actually, in the world, on the street, right amongst the throb of it all. The rumour was that Ted had been travelling non-stop for over twenty years. A lot of the time I was employed to shoot video on those trips, but I always carried a stills camera with me. In my mind, I’ve always been a photographer more than a motion picture guy.

How has that balance worked?

It’s been a tricky one. I’ve had more work shooting moving pictures than stills, especially these days, but I consider myself primarily a stills photographer. I don’t know why. It might be because I’m not a trained cinematographer and I’ve always winged it. The first big 16mm shoot I had was three weeks in Brazil and my assistant had no idea about loading film, another inspired choice, so we ran thousands of feet of film through the cameras and hoped for the best. I remember, weeks later, being genuinely surprised when I spoke to the telecine operator and he reported that there were pictures there. Shooting motion is not that different to shooting a still, after all the light is the same and the emulsion is the same, but there weren’t as many guys doing it and that niche allowed me to get more work. Some surf photographers shoot weddings on the side, some shoot fashion and swimwear, I did video. It’s always been challenging to make a living out of taking surf pictures, it’s been described as ‘starvation on the road to madness’ so we all diversified in one way or another to survive. Shooting 16mm was my way of paying the bills. It was my job.

In your profession day rates are sent from heaven.

Exactly, and I was happy to do the video work. Starting out, Litmus was shot on Hi-8, then I started shooting film, super 16mm, and it was a blast. I was in the water a lot and it was a great gig. The beauty of shooting film, besides the hypnotic whir of it running through the gate, is that once the sun goes down you knock off. There are no laptops, no downloading of cards and all those digital chores that have us working 16 hour days. You are free to experience a taste of the location you are in and that in turn affects what you end up shooting.

How do stills and film complement artistically?

It’s a bit of a transition. To me the major difference between stills and the moving picture is the end point. With stills, you do a quick edit, send the images to your editor and the job is done. With a movie, it’s a far bigger commitment. It can take years. But I did make a few surf films and there is something magic about pairing music with moving images and combining these two arts to create a work that is greater than the sum of its parts. Richard Tognetti, artistic director of the Australian Chamber Orchestra and I have worked together a lot in this field. Richard always says that when done properly the pictures can make you see more in the music and the music makes you hear more in the pictures.

What have you and Tognetti worked on?

We’ve worked together on several concert performances over the years. They always feature live orchestra performing in front of video projections. They were The Glide, The Crowd, Nothing, and The Reef. Can I send you something I wrote about our concert Nothing?

This is highly irregular, but ok.

Richard Tognetti and I have collaborated on another concert which premiered in Slovenia last month as part of Festival Maribor. It featured classical music and video projections based around the concept of ‘Nothing’. The two-and-a-half-hour concert polarized the audience who I believe were expecting to be entertained. The projections contained graphic footage of burning bodies, child birth, a sequence shot inside a Geelong Bingo Hall and another of teens eating lunch at the Geelong McDonalds. A concert highlight was semi-naked soprano Aleksandra Zamojska singing Beethoven and Handel beautifully, another was Barry Humphries reciting nonsense rhymes to the music of William Walton. Humphries wrote of his experience for The Spectator magazine in the UK: “My efforts were at the beginning and end of a long programme featuring the New York avant-garde of the Sixties, including a work by John Cage which contained a long movement of complete silence disturbed only by the sound of the audience leaving”.

Can you tell me about one roll of images you’ve shot that have really moved you?

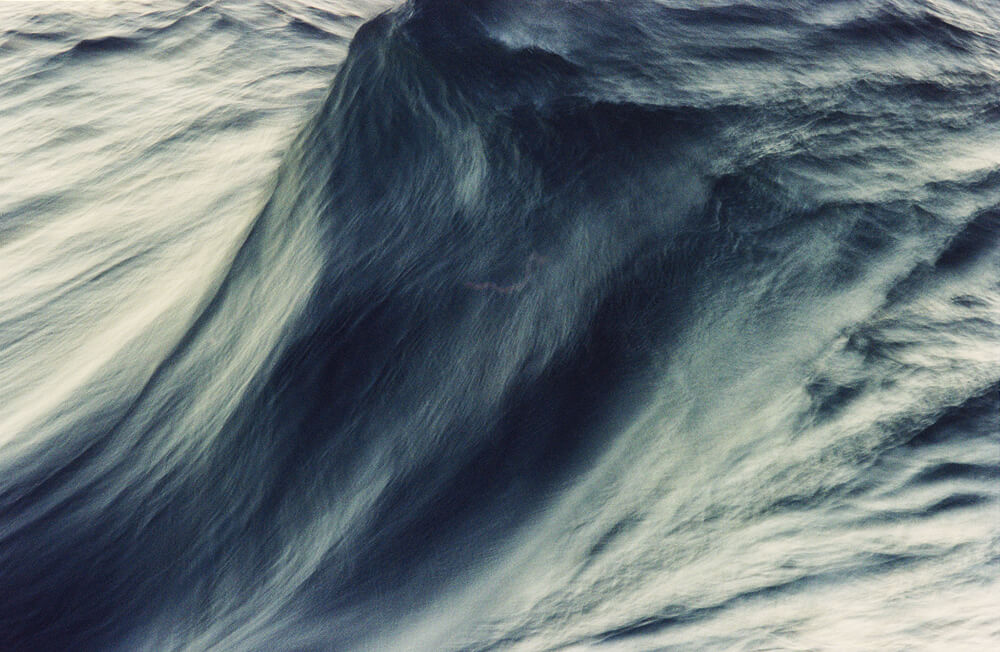

There was a single roll I shot in Hawaii in the early ‘90s. Back then you took your film to Foodland to be developed. You took it to the counter in this little Kodak bag, this was a roll of Kodachrome 200, and dropped it in a box. It was quite the scene. Every photographer on the North Shore was dropping their film there. Except one year Dean Wilmot somehow brought his own E6 processor out from Australia and was developing his own film, with mixed results, in a dingy garage. Our film was sent to the mainland to be processed and three days later you got your boxes of slides. It seems archaic now, but it was unreal. That sense of anticipation. I’d shot this particular roll and I remember sitting in the car park at Foodland and opening the cardboard box and holding each slide up to the interior light. The pictures were different to anything I’d seen. Usually my photographs looked similar to pictures I’d seen in surfing magazines, sure most of the time mine were out of focus and the timing was off or whatever, but they had that familiar feeling. But not this roll. They were from a shorebreak I’d been bodysurfing called Keiki. It was a quiet but stunning stretch of sand that provided a reprieve from the high energy and ego of Kodak Reef (the beach from Off the Wall to Pipeline). I’d swum out late one afternoon into these lined-up swells that came out of deep water before dramatically standing up into long walls and exploding onto dry sand. Those pictures were like nothing I’d ever seen before.

Was this roll a ray of hope in an otherwise dark world?

It’s an awkward thing to do really, walk around with a camera all the time and have to see everything when it is expected of you. It’s much more pleasant to just go through life living, rather than observing. Clumsily attempting to dissect the fabric of other people’s lives is exhausting. But that one roll changed things for me. It’s funny that memory is still there, of opening that box and realising that I’d created something unique. In retrospect, I probably should have pursued this line more aggressively but that’s not my character.

You’re quite a sensitive soul. I can imagine you’d be the kind of guy who’d cry at the opera?

I don’t really love opera. The music is fantastic but there is too much theatre for my taste. You’re right though, I’ll cry at the drop of a hat, often at the most predictable times. Life is so full of other shit that tries to grind you down. Shedding a tear can be a joy, at least it means you are feeling something. Life is designed to wear you down, but then you have all these little peak moments. It can be as simple as swimming in the surf when the sun is rising or setting, or beneath a full moon.

Your terra firma photography is quite voyeuristic and captures candid everyday life. Do you feel that’s the same with shooting the waves? I look at some of your photos and I get the sense the waves don’t know you’re there, like you’ve snuck up on them and caught them going about their daily life.

That question was poetry Sean. Look, photographers have all these techniques they use to trick you into feeling something. The whole thing is smoke and mirrors. The longer I’ve done it, the more I’ve tried to strip all that shit back. It’s not as big a deal for me with seascapes as with other genres. Turner used to dramatise an ocean scene and if he did, then its kosher, and besides water lends itself to that. It’s a grand and at times chaotic environment by its very nature. To that point, as you say it, sneaking up on the ocean and catching it unawares, it’s the same philosophy of being truthful to what was there, even to how you came to be there, to the events that helped it unfold. I have a philosophy when I’m taking pictures that I never construct a situation. Contrivances are of no use. I can’t control my own effect on a scene; just by being there I can alter the dynamic. But what is in the world is enough, there should be no need to mess with the natural order of things.

There’s the artistic element of shooting these images, but there’s also a very large physical aspect, swimming out there amongst some wild ocean carrying a camera the size of a concrete block.

I’ve swum out in some wild, crazy oceans but I’m not particularly fit. It’s mostly mental. If you’ve been surfing long enough you swim out and you know where you should be and where you shouldn’t be and you pick up on the energy of the water. We all get smashed and there’ve been times where I’ve been in trouble. Being fitter might have been nice, but I’ve seen supreme athletes struggle in the ocean. It’s a different kind of physicality. If you do it long enough and you spend years in the water bobbing around your body adapts to it and you get to a point where you’re comfortable. And besides fat floats! The ocean, as frightening as it can be, is also quite forgiving. It’s water after all, so generally speaking the worst thing that happens is that you get washed in and bumped around a bit. You can get held down longer than is comfortable but it’s just like surfing or life really; if the shit hits the fan don’t fight it, just let the energy take you out of there.

How have your ocean images evolved over the years?

Funny you ask that, I’ve been going through all these pictures, boxes of old slides for this book, certain there was going to be something that slipped through the net. I’ve been like a kid on Christmas morning… but there’s nothing there! I picked the eyes out of them the first time and in the old days we had to physically send our original slides to magazines in the mail so you can imagine how many actually made it back. I’ve got sheets of slides and the only two missing from the roll are the only two good pictures! I’ve been holding up all this hope that there’s been boxes of slides down in this cupboard in Tassie and it would be this El Dorado of lost gold in there, my superannuation fund. I go through it and it’s all rubbish; out of focus, badly framed, just terrible. This book was going to be chronological and it still might be at this point, but I showed my missus a rough layout I’d been mucking around with last night, and she said, “Why have you got the dates going from ‘91 to today? All the photos look the same! They’re not in any way different.” She looked at one and asked, “When did you take that?” and I replied, “Twenty-five years ago,” and then she points at another and asks, “What about that one?” and I said, “Two weeks ago,” to which she told me “They’re the same!” And she was right, but there’s every chance the new ones are actually worse.

Your favourite coastlines to shoot?

Hawaii is a gift. Anywhere you spend a lot of time, but I’m of the opinion you can take great pictures anywhere. If you put the time in, places begin to reveal themselves and you get to know them. It’s like being a surfer, you tap into the rhythms of that coast and the weather conditions, but Hawaii, I’ve spent a lot of time there over the years and I love it. Australia… look, Cronulla was hugely influential on me, the reefs there. Now I’m on the south coast, inland over the mountain, and while I’ve been coming down here on and off for thirty years, I’ve had to relearn things. There are nooks and crannies everywhere. But to be honest; Victoria, Tasmania, Western Australia, Tahiti, Ireland, there’s no such thing as a bad coastline.

Do you look at an image of an empty wave or a sweep of ocean and assign an emotion to it? Does looking at the ocean evoke something different every time?

I suppose with any art, sometimes the pieces just fall together in the right way. To succeed a picture needs to transcend its medium. What I’ve learned after years of trying is that the nuts and bolts don’t count for much. A picture can be rough as guts. It can be soft, grainy, underexposed or all three which mine often are, but if it finds a resonance, for whatever reason, people will react to it. I don’t reckon that answered your question at all.

No, I’m getting used to that. Two decades ago swimming out and shooting photos of empty waves was almost unheard of, but today it’s become an art form and a movement in its own right and there are guys shooting empty waves and making good livings out of it. Why do you reckon this has happened?

Obviously, water is photogenic. Waves and light together, it’s a heady combination. There’s a movement today toward people only shooting waves and I don’t know whether it’s called ocean art or wave art but people simply love looking at those pictures. Surfing photographers have historically always taken pictures of waves, but they were usually done sporadically, while on assignment shooting something else. Drew Kampion edited a terrific book, I think it was in the early 90’s, of wave photography that was hugely popular. Artists like Denjiro Sato, Warren Bolster and Don King were masters of their craft.

Why do you think they resonate? Is it because they have a sculptural element? Is it because they are all one-offs, all totally unique?

Could be. But I wonder whether from our own experience of time spent in the water as surfers or swimmers or coastal people, we recognise that environment from somewhere in our own past – one afternoon when the sun was going down and the water felt good, maybe it’s evoking some sort of memory in us? I don’t really know. Maybe that’s too simplistic. It’s not just surfers who like looking at them. I like landscapes of mountains but I don’t want to climb one. Waves are a natural phenomenon. Untamed, overflowing with myth and legend, the sea is in us as human beings, it has been since we crawled out of it. We’ve come from water and whether you live by a beach or not it’s still in us, somewhere in our being. It’s also how we got around until the last hundred years. The oceans separated us but connected us.

You were once quoted saying that the last the things the world needs are more photos. How do you make an image mean something with the ubiquity of images in the digital age?

I suppose it’s pretty frightening really, when you think about it, it’s enough to stop you getting up in the morning. Perhaps I’ll start working with photographs and films that already exist? One area that interests me is surf-cams. These robotic cameras that surfers use to check the conditions. They are continuously streaming pictures of hundreds of beaches worldwide, there must be moments of beauty and art in there somewhere. Photographs have become so…

Meaningless?

I don’t know. What does anything mean?

I was asking you.

Why would I travel the country, spending money I don’t have, to make pictures of random strangers in the street that can, due to the medium, cost upwards of $25 a shot? And then spend months going over them to discover that most are failures that tell me nothing. Developing, scanning, finishing. What kind of fool does that?

You’ve been doing it for 30 years now.

It’s useless! It’s a waste of time! But a pleasant one at least. The truth might be that I’ve never taken an interest in anything else. Our lives are bombarded with manufactured spokesmodels trying to sell us shit we don’t need and can’t afford. If I thought about the state of the world too hard I’d never leave the house. And I enjoy nothing as much as wandering around with no agenda feeling like I’m part of a larger world that is vastly more interesting than the inside of my house… so the take home message is don’t think!

Do you still look at the ocean like staring at a campfire, almost hypnotised by it?

Of course! Oh my god. I have hundreds of perches all around the world and if I go back to a break I’ll walk and check it from the same spot and over the years I’ll go back again and again. It’s the same when you swim out. The reefs don’t change, the rocks are the same, the water washes in and moves across and around in familiar patterns. In our heads, we keep all this knowledge of underwater landscapes. You ever think about that? Surfers carry around all this information. The topography, the bathymetry. We’ve been rolled across that reef so many times we don’t forget it, all the nooks and crannies. It’s a secret world. I can’t see the ocean from where I live now, but I have accurate maps in my mind of underwater landscapes in Tahiti, Hawaii, Indonesia, Ireland…the list goes on. Imagine all the knowledge that is in a lifelong surfers’ mind? I live next to a river now, so I sit and watch the river and it’s a different beast altogether. I know nothing about rivers but I can lose myself for hours just watching it flow.

Broken – Volume 1

Photographs and text by Jon Frank

Foreword by Andrew Kidman Afterword by Sean Doherty

Available at jonfrank.org/broken

[shopify embed_type=”product” shop=”coastalwatch-book-shop.myshopify.com” product_handle=”new-surfing-world-issue-392″ show=”all”]