IN THE CANOE WITH MR. BRASUR

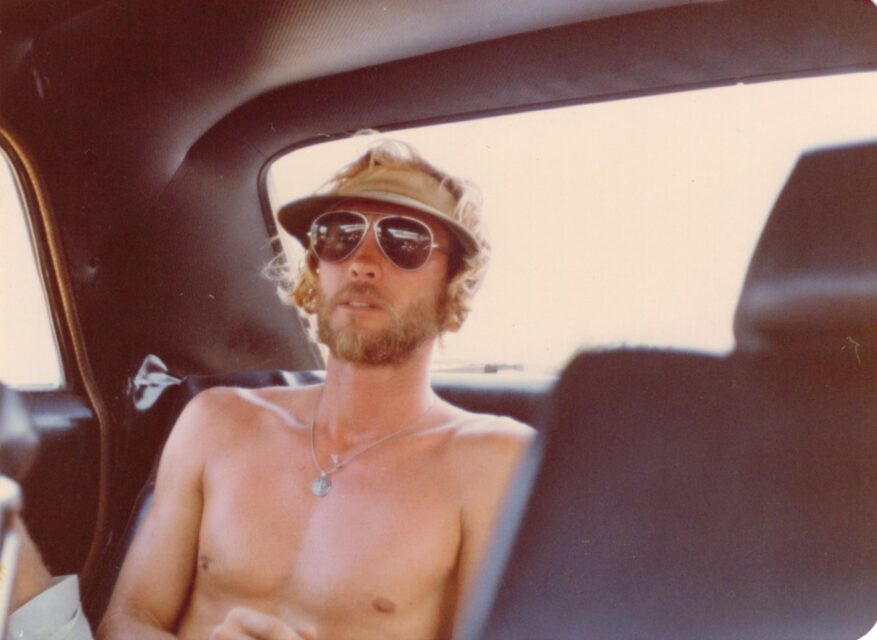

Captain Seaweed Part 2

By Lance Knight

I originally went to Singapore in early ’91 because I was looking for a ship to buy. Singapore’s a good place for ships. I went up there and spoke to a couple of shipbrokers, had a look at a couple of old barges, but there wasn’t much there. I was going to go on to Europe, but I thought before I go, I’ll duck over to Sumatra, clear my head and go surf Nias.

I travelled by train to Penang in Malaysia and then to Belawan in Sumatra on a small cargo boat, sleeping on deck with my board and backpack. I got to Sumatra on February 25, to Sibolga, then caught the old timber ferry Sumba Reseki out to Nias and spent a week surfing beautiful, uncrowded waves.

I got back to Sibolga and hopped on a bus down to Padang. That took about a day-and-a-half, and it was just a horror show. It had been raining and all the roads were washed away. I reckon I saw six bus smashes, where the buses had just gone over the side. The roads were just insane around these cliffs; no railings and they just don’t slow down. Our driver had Indo dangdut music blaring and you’re stuffed into the bus like sardines, with all kinds of bags, crates of chickens and people laying on the floor. Everyone was smoking Gudang Garam. Up the back I put a towel over my head and hoped for the best. Two days later coming down through the mountains of Bukittingi I thankfully laid eyes on the ocean once again.

Almost as soon as I got off the bus in Padang this truckload of police pulled up and insisted, I jump in with them. I didn’t know what they wanted, but they were very insistent, so I hopped in. I thought, what’s going on here? They drove down to the beach and there was this huge reception, with dancers and politicians and dignitaries all gathered around under these big banners. It turned out it was Padang Tourism Week and they’d organised this big reception. The only trouble was, they couldn’t find any tourists. So, these police had been sent out to round up anyone they could find, and I was the only one. So, I had to sit there, in the front row, through all these speeches and dances, as the honorary tourist.

When it was all over, the dancing group came up to me. It turned out they were students from a Padang university, and took me in their minibus to the Tiga-Tiga Hotel where I booked in. There I met a fellow namedHenry who spoke quite good English and offered to show me around Padang, starting with a local nightclub. As we walked in everyone started clapping and girls were coming up to me and Henry. I thought they wanted to meet me, but then Henry got up on stage with his band and started singing word perfect Elvis Presley. Henry was the local rock star.

I walked around the town for two days, trying to find a boat to come out to the Mentawais. I walked along the river asking if there was a kapal (fishing boat) to take me to Sipora, but everyone was either working on their boats or didn’t want to go that far. Then Henry said to me, “The doctor is going to Sipora tomorrow. I will ask him to take you.”

Doctor Manir was an Iranian doctor based in Padang who would later inspire the formation of Surf Aid. He was coming over to Sioban to treat some people, so I got a lift down to the airport the next morning and flew over with him. I think it cost me $50. I had one board, a backpack, a big bag of rice and as much water as I could carry. The plane landed on the old grass wartime airstrip, turned around and took off. Dr Manir went off into the village, and I was left alone.

There was no road, so I started walking along the beach. This old guy came along paddling in a dugout canoe, and he pulled into the beach. He introduced himself as Mr. Brasur. I couldn’t speak Indonesian and he couldn’t speak English, but we communicated by sign language, and I offered him some money to give me a ride. I wanted to get to either end of the island. He took me into Sioban where he had another canoe, one of those big ones with an outboard on the back. So, we jumped into that, and went down and anchored the first night down near Telescopes. I had a surf at the next point along, and that night we slept in a hut on the beach up near Tuapejat. I can remember all the mozzies buzzing around, and I wasn’t taking any anti-malarials. We ate with a fisherman and his family, and I gave them some of my rice. The children never took their eyes off me.

We headed south the next morning and came round the southeast end of Sipora. The weather was shifting; glassy one minute, then blowing with big rain squalls. Mr. Brasur had this old outboard with no cover on it, just a bit of string to pull-start this thing. And down the middle of his canoe he had all these bottles, bits of plastic, anything that could hold petrol, no caps on them. He had a bit of garden hose, then when one bottle would run out, he’d just pull it out and shove it in the next bottle.

As we were just coming past what seemed to be the end of the island, this big squall came through. I wanted to keep going toward the bay marked on my chart, but Mr Brasur shook his head, pointing to a gap in the reef. We started heading in toward a village I’d learn was called Katiet.

We went in through the keyhole; he must have known his way in there. As we started coming in, I saw all the spray coming off the back of the waves. I was just looking into this incredible righthander. I’ve never forgotten that moment. In all my life I’d never seen a wave break so perfectly.

Landing on the beach, all the people came out of the village. I wasn’t really paying too much attention – I was just looking at this righthander. It was a solid six foot. I thought, I’ve got to get out there. I pulled the board out of the cover and all these men came over, picked my board up, feeling it, tapping it, looking around it, running their hands over it – all the canoe builders. They couldn’t believe it. The way they were looking at this thing, they’d definitely never seen a surfboard before.

Then from a modest house, a tall stately looking Indonesian gentleman walked down the beach towards me. We shook hands and I introduced myself tapping my chest with the only Bahasa I knew – “Nama saya Lance.” And so, I met Pak Hosein of Katiet. I instantly felt a connection with that regal man. I thought he was the kapala desa (village head man), but he wasn’t. He had some kind of authority though. Pak was talking with Mr. Brasur, and I half-noticed my gear disappear up to Pak’s house, where I met Pak’s wife Ida (Mumma) for the first time. I had a little mozzie net and a bedroll with me, as I’d planned to sleep out on the point, but Pak insisted I sleep at their house. He kicked a couple of his kids out of their room and put my gear in there. When I came out Mr Basur was gone. I’ve never met him again.

By this time the whole village had turned out. There were probably 150 people. I just grabbed my rashie and put my helmet on and ran down the beach and paddled out. I sat in the channel for a little while just watching it, going, “Can I? Will I? Won’t I?” I think it must have been high tide because it wasn’t too bad. It didn’t look dangerous. I paddled out and got one little one and then there was one wave that picked me up, probably the second or third wave – bang! – on the Surgeon’s Table, straight across the reef. But I paddled back out, got a few more waves. By this time there were people up in the trees. All the young guys had climbed this huge tree that used to be in the keyhole. There must have been 100 people up in this tree, screaming. Every time I got a barrel these people were screaming. It was just insane.

Every night after dinner they’d shut all the doors and windows, light the fire and throw all these green branches on it and fill the place full of smoke. You could hardly breathe. That’s how they got rid of the mozzies. But every night you’re in there suffocating, sweating like a pig. They really looked after me though. They fed me. All I had was a big bag of rice. I gave them the rice and they just fed me for a couple of weeks – fish, chicken, rice – I just ate with them every day.

I really didn’t know how long I was going to stay there, or what I was going to find. But the surf was perfect every day. It would drop down to three-foot one day, and a couple of days later it would be back up to six feet again. It was just clean, like glass. You couldn’t even see the waves coming.

I tried to give Hosein some money for food, and he just waved me away. I had a pretty big first aid bag with me and every day the kids would come down and I started putting Betadine on their sores. The next morning there would be twice as many kids. I gave out all my Panadols and aspirin to their parents. They obviously had malaria; they were pretty sick some of them, but I couldn’t do anything to help them.

I surfed perfect waves for hours every day. Some days I was out in the water all day. I had a big straw hat and used to sit out there with my straw hat on and wait for the right waves. I never saw another surfer. I went across the reef heaps. Every day all the young guys used to come down the beach. They used to fight to carry my helmet, my block of wax, my towel, this little procession down the beach every day to go surfing.

One day Hosein and his sons came down the beach and the wind were just starting to ripple up a bit and he started pointing to the other side of the island over the hill. He knew the left would be offshore, and he took me down into the village where there’s this rainforest track out the back. We picked up another hundred people and set off. I just remember seeing my board being passed by this line of hands.

Two hours later, I stood on top of the hill with Pak Hosein and gazed down over one of the most breathtaking scenes. A sheer panorama of green descended below us. To the horizon the bluest ocean stretched away as far as I could see. I turned to Pak and shook his hand. He must have read my face. He knew this must be a special moment for me. For so long I had looked at this bay on my uncle’s charts, and here it was before my eyes. In the distance, a beautiful palm-lined sandy beach ran into stands of tall Mentawai trees clinging to the reef. I could make out the lines of breaking waves in what appeared to be several lefthand points, and further to the west a small righthander. Descending the mud slide that served for a track I finally stepped onto a beautiful white sand beach.

The first day I surfed the left was a bit scary on my own. I didn’t quite know where to sit, and it was one of those swells where it’s dead flat, then all of a sudden, an eight-to-10-foot set would come out of nowhere and break on my head. The first wave on my backhand took me by surprise. What had at first looked like an easy wave accelerated into a cavernous, hollow wall. Gripping my rail for dear life, I pig dogged into the second section and got spat out into the sun. It felt like I’d been shot out of a gun.

The next day I did it again. This time Pak, a bunch of kids and I walked the long way back around the point. We had to climb over piles of white, dead trees. It must have been such a forest once.

A couple of days later I saw this blue ship coming round the point. I’d seen the boat from Mr. Brasur’s canoe one day down the other end of the island. They were going to salvage a bulldozer that had fallen off a timber depot, and they were towing a big barge. I saw them pull up, they anchored just out in front of the keyhole, and I saw guys pulling boards out. I’ve gone, oh no. I was on the beach at the time, so I grabbed my board and paddled out to them. They were pretty surprised to see me.

By that stage I was pretty ready for some company, but I was disappointed because I knew this place was special. I felt a bit sad that word was going to probably get out. I paddled over and introduced myself and we had a couple of waves together. One of them was a guy named Martin Daly, who was wearing orange overalls. He asked me if I wanted to go and have a beer. So, I paddled out to the back of the boat and had a beer and sat out the back of the Indies Trader and had a bit of a yarn.

Martin asked, “How did you get out here?” and I told him I came down in a canoe. He told me what they’d been doing, because they had all diving gear, a decompression chamber in the hull. It wasn’t set up for surfing then. They’d just been working, mixing business and pleasure, looking for a bit of surf as well. The waves were probably about four feet that day, really oily, overcast, nice, and they just anchored up overnight and we surfed the next day.

Martin asked if this place had a name. I replied that the village was called Katiet, but It doesn’t seem like anyone has ever surfed here before. He asked, “What are we going to call this place?” I said, “Buggered if I know. I’ve just been thinking about that dead tree over there, on the point. I was going to call it Dead Tree Point or something.” And he said, “No, it’s Lance’s. You found this place. I’m calling It Lance’s Right.” He then said, “By the way, do you know about the left we just saw around the back?” I replied that I did and had surfed it a few days ago. Martin looked at his crew and said, “Well, I guess that makes It Lance’s Right and Lance’s Left!” We all had a laugh and raised our beers, and I honestly didn’t think much about it after that until I was back in Australia.

Then Martin said, “We’ve got to go back to Java. You’re welcome to come with us.” I thought about it. It was either take this offer or I’m going to have to wait for another boat to come along. I also still had to honour my promise to the Lord Howe Islanders. So, I got all my stuff from Pak Hosein and Ibu Ida and said goodbye to them and jumped on the Trader. I wouldn’t see them again for another 13 years.

We spent three days going back to Java, surfed a couple of places. There’s one place, it’s just a reef out in the middle of nowhere, you can’t see land, just a reef out in the open ocean. Martin took me over and showed me Krakatoa, that was insane. Then I spent a couple of days in Jakarta partying on with Martin. That was pretty wild. The nightlife was unbelievable. My senses weren’t prepared for the noise and Asian bustle of Jakarta. Martin and his crew had this big Indonesian mansion in the old colonial quarter as their base, and Martin had this big white Mercedes. I remember one night I tried to go home in a taxi about midnight. The next minute the taxi got run off the road by the white Mercedes, Martin hops out with a handful of money, throws it at the driver through the window, tells him to bugger off, grabs me, throws me in the back of his Mercedes and takes me off to this other nightclub ’til five in the morning. I was glad to get out of Jakarta by the end of it. One of his guys had a girlfriend down the coast at a place called Cimaja so he took me down there and we surfed there for a couple of weeks.

I travelled on through Europe, searching for a ship. After another month I’d found nothing. I came back to Australia broke and empty handed and the whole Island partnership was beginning to fall apart. Not long after that I went up to New Guinea to look at another ship. I didn’t buy it, but the people I went up to see offered me a job. I spent six months up there driving a little survey ship, the Western Venture.

I got a brief handover and thumbs up from the outgoing master as he climbed into the helicopter and in a deafening whirring of blades he was gone. Months went by re-mapping the Fly River and the outer barrier reefs in the Gulf of Papua. To keep my inner surfing self happy, I carved a wooden surfboard from a solid slab of cedar. Halfway up the Fly River an old WWII veteran lived with many local wives and at least 20 children, who ranged from grown men to babies. As big trees came down the river, they would all paddle out in canoes and jump on the tree and paddle it to shore. The old fellow would connect a chain to an old army tank and drag it up to his bush sawmill. He gave me a six-foot offcut for a carton of soap. Five hundred miles upstream at Kiunga, I would get my crew to tow me around the river on the board with the work boat, in denial of the sleeping crocodiles sunning themselves on the riverbank. The water was so thick with sediment when I fell off it instantly went black.

It was my crew who told me about the Bursea, a ship laying derelict down in Cairns. I placed a bid at the receiver’s auction and by the narrowest margin, I won. Lord Howe Island Seafreight was born. My old crew from Yamba joined me in Cairns, and after an epic voyage nursing the tired little ship down the coast of Australia we dry docked in Ballina and finally got home to Yamba. We renamed the Bursea the Island Trader.

When I got home to Yamba, I told a few friends. I said, “I’ve found this insane wave.” I showed them a few photos I’d taken, and just told them it was somewhere in Sumatra. I was always planning to go back. Martin and I actually stood on the back of the Indies Trader and Martin said, “This place is unbelievable. We’ll keep this a secret.” We actually shook hands and agreed this would be a special place and if he took people back here surfing, he’d never tell them where it was. But you can’t keep a secret like that. It’s just impossible.

Word eventually got out. I remember one day I pulled up at the point at Angourie and Grant Dwyer, from Fandango surf shop came up to me and said, “They’ve found your wave.” I looked at him and said, “What do you mean?” And he said, “They’ve found your wave.” And he had this magazine article, and it had this story in it saying, “Sorry, we can’t tell you.” And it had this big spread on the Indies. After that every time you opened a magazine, there was a picture of Katiet.

It was March 1992, exactly one year from when I’d found my wave to when I came back to Lord Howe Island with their ship. This was a significant moment in my life. I got there in the middle of the night. It was a filthy night, blowing a gale, raining, and I had all my search lights on as I brought the boat in through the gap in the reef. There were only probably 30 cars on the island back then, but they all parked along the hill and were shining their headlights across the lagoon. I’ll never forget it. We’re coming in through the reef, and just as I’m starting, they called me up and said, “Turn your radio on, Lance.” I turned the local radio on, and they played The Doors, Riders on The Storm as we were coming in. Seriously, mate, I had tears in the eyes. We tied up and there were about 300 people all come running down the wharf carrying cartons of beer to come check out their new ship.

That was my life for the next 15 years. I found myself a single dad to Keelan and Tasman, and they sailed with me on my fortnightly voyage to Lord Howe and back. I sailed through cyclones with those two little boys sitting on a mat on the wheelhouse floor. They didn’t know it, but we were quietly shitting ourselves. We had little grab bags for the boys with their little miniature wetsuits and life jackets all sitting in the corner ready to go a few times. We never knew if we were going to get through some of those storms. I’m not joking, mate. I’ve seen some ocean out there that’d scare the shit out of me.

Anyway, that was their life for the next 15 years too.

– As told to Tim Baker