THE IMPOSSIBLE SUNDAY

The Eddie returns to its roots. And roars.

By Nick Carroll

[Excerpt from SW420, available here].

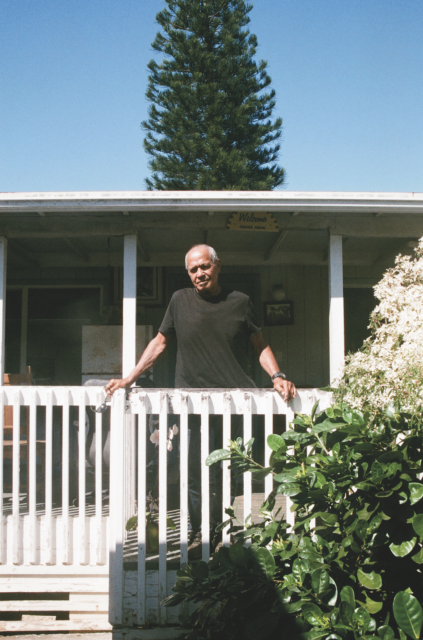

“Here we are,” says Clyde Aikau. “Last of the last.” He takes a breath, holds it, and breathes out his next words. “And it sucks to be the last of the last.” Clyde’s eyes turn away, and inward. He asks the question nobody can answer. “Where everybody went?” We are sitting in the open garage space just outside the Aikau family home. The home and the garage are tucked into the western corner of a big, open piece of land stretching away and up toward one of the ridges above Honolulu. The land is lightly grassed and dotted with gravesites; this is the town’s Chinese cemetery, leased by the Aikaus since they arrived on Oahu from Maui 64 years ago. It’s a lovely sunny day with a light tradewind blowing. It’s five days since the greatest surfing event anyone’s ever seen.

January 22, 2023. Nobody knew that day would happen the way it did. There were no portents, no sign that surfing’s most profound mythology — loss, sacrifice, and a humble yet quietly glorious redemption — was about to play out before the world’s eyes.

The entire week leading up to that impossible Sunday was as gentle and pretty a January week as I’ve ever seen on the North Shore of Oahu. Me and my buddy, Hannah Anderson were there to shoot some innocuous video projects and sneakily surf our brains out. We weren’t expecting giant closed-out Waimea Bay, spectators being washed into the lagoon, a range of people leaping into mid-air off saltwater office blocks, and a cruisy, yet naturally skilled lifeguard winning an event full of the biggest names in Charger World, during what amounted to his lunch break.

We had no idea what we were in for. But neither did anyone else. The Eddie Aikau Big Wave Invitational was 37 years old and had run just nine times, at the beck and call of the same ocean into which Eddie himself had vanished back in March 1978. If that ocean didn’t send a full day of 20’–30’ surf to Waimea, the contest didn’t happen, which usually meant it didn’t, sometimes for years. “The Bay calls the day,” in the words of the late George Downing, who’d made the Eddie call more times than any sane human should have to.

Yet much had changed in the years since George last made that call. The Eddie’s long-term partner Quiksilver had ceased its involvement with the event, and in tandem with this shift, the Aikau family had decided they wanted more say in how their brother was remembered.

Suddenly there was no mega-corpo backer or famously huge winner’s cheque — indeed for a while, nobody was super sure if there’d be any prizemoney at all. Not that anyone seemed to mind. Among the invitees, the general sentiment was best summed up by Zeke Lau: “We’re not surfing for prizemoney anyway.”

But what would a non-corpo Eddie look like? Hannah and I got a clue about that when we wandered down to the Bay early on January 21 to watch the event set-up. At that point, 24 hours before the carnage, the scene at Waimea was positively bucolic. The surf was dead flat. There was no movement in the bay; virtually nobody on the beach at all, except for some military people who were playing Frisbee.

Up in the beach park, a couple of trucks were pulled up on the grass, and some older gents were quite carefully beginning to unload some scaffolding. The whole thing had an amazingly cool club-contest-morning vibe. Around 7:30am Clyde showed up with his son, Ha’a. It was like the club president had arrived. He strode around: “Bring that truck over here! Let’s get this show rolling!”

Prompted by Clyde’s arrival, everyone got to work, but it wasn’t with the ruthless efficiency of a modern pro sports event set-up operation. Instead, there were old family friends, relatives, and a young guy who had just shown up out of nowhere and offered to help. The old blokes took their time with the scaffolding. Liam McNamara, event director, whose kid Landon was in the event, leaned against a tree and smiled. “I think we got this,” he said.

Slowly through the day, the human energy began to build, and all night it felt like the whole North Shore was engaged in an awkward kind of party. It was really hard to sleep — not because of any tension surrounding the day to come, but because there was so much noise. People everywhere, dogs barking, sirens, yelling.

Around 1am, the swell hit Buoy 51001, a few hours from Oahu, at full force: 23 feet at 19 seconds — exactly what Ross Clarke-Jones kept saying when he pulled up around 5am to give us a ride to the Bay. “23 feet at 19 seconds!” he half yelled. “23 at 19! We go!”

As soon as we pulled out on to the Kam Highway it became super obvious why the night had been so hectic. Thousands of people were scattered up and down the highway east and west of Waimea, trudging through the pre-dawn blackness toward the Bay and dragging with them everything you could imagine – pillows, blankets, coolers, baby carriages, tents, surfboards, bike trailers, the lot.

The traffic was insane. Amid the glare of headlights and roadside dust and flashing cop-car lights, the surfers themselves were trapped. Mark Healey and Billy Kemper were five cars apart a kilometre from the Bay for nearly an hour, calling each other.

“Where are you?”

“I’m here?”

“What?”

“How are we gonna get there?”

Emi Erickson listened to Led Zeppelin while husband Mike tried to find a way through. Emi is a cool cat, but this was Eddie morning. “I gotta… surf!” she yelled to a truckie who wouldn’t let her pass. They pulled on to the wrong side of the road, where a cop told them, “Yeah, just go.” So, they did.

A few cars away, Pete Mel and Jamie Mitchell sat and gazed at the human traffic in quiet amazement. “Like fricken… Woodstock,” breathed Jamie.

He was right — but this was no Woodstock. Up ahead of them, people were climbing on to concrete barriers on the roadside, trying to gaze into the half-light. Trying to see what 23 feet at 19 seconds looks like.

Clyde is trying to tell us the story of Eddie. I could recall Clyde telling me the same story, 33 years ago, back in early 1990, just weeks out from the Eddie that changed history. The 1990 Eddie, with Brock Little and the barrels and the impossibly sketchy drops, eventually won by Keone Downing, George’s son.

That was the year when everyone saw what the Eddie might become. Back then, we sat up underneath the heiau above the Bay one sunny afternoon and Clyde told me the story over three hours of carefully recalled, at times meticulous detail. Now he told it with much of that detail stripped out, yet with the physical and emotional core intact. Somehow, it had even more power.

I realised we were hearing a story that was in the process of becoming a myth — a tale boiled down to its essence, easily told and easily repeated, designed to be thrown through time, far down the generations, to land who-knows-where. Myths developed like this can travel through cultures for hundreds, even thousands of years. Like the story of Maui the fisherman, who drew up the Pacific islands with his line and hook, or the Aboriginal stories of the coast during the sea level rise 10,000 years ago. Little story seedlings with a grain of something at their core, waiting to be re-grown.

This one’s managed to travel for about 50, so far. Maybe it’s the only story in all of surfing.

I was stunned to hear from a number of people who are really au fait with surfing and been around for a long time in some cases, that they really didn’t know the story of Eddie Aikau at all, that they just had a larger-than-life figure in their imagination, and they knew more of the contest than they did of Eddie himself.

So here it is.

Edward Ryan Aikau, born on Maui, May 4, 1946 to Solomon and Henrietta Aikau, third of six children: Frederick, Myra, Edward, Gerald, Solomon III and Clyde. Hawaiian to the bone. In early 1959 Sol – ‘Pop’ – moved the clan to Honolulu, to give the kids a bigger start in life.

“We all went to school just here,” says Clyde, walking us around a corner of the property, and pointing to a bunch of kids running around the Pauoa Elementary School playground. Well, not all of them. Clyde was given to study — eventually he went to the University of Hawaii and pursued a degree in sociology. Eddie’s mind was mostly just on the water. He was a quiet kid who rarely went to school and rarely fell ill. The family called him Ryan more than they called him Eddie. He and Clyde made little paipo boards out of plywood and surfed The Wall at Waikiki with the rest of the grommet population.

By the time he was 15, Eddie was definitely king of The Wall. But could he be king of anything else?

These kids were stuck in the backwash of a raw act of colonialism: the US-business-led destruction of Hawaiian sovereignty, and the re-invention of Hawaii as both a forward base for the US military and as a hula-hoop postwar holiday franchise for mainland America.

“Growing up and being Hawaiian back then,” says Clyde, then stops. He is looking for the exact word and finds it. “At the time, it felt uncomfortable to be Hawaiian.” Imagine. Uncomfortable in your own land. How do you find your way through that?

Clyde cuts to the chase. “Haoles came in and took everything,” he says. “I’m not one to grumble about it, but it’s a fact, even today. By your laws, you had no right to be here. And you took it and bent it so you could be here.

“We were beginning to know (about Hawaiian history). We started to change the attitude of not being good enough. But for a while, growing up in our youth, it felt uncomfortable.

“And for me and Eddie, staying in the water, it kinda brought us closer to who we really were.”

Water as belonging. That’s how Eddie became the first great Hawaiian surfer at Waimea. That’s how, in 1968, he got the first and only lifeguard job on the North Shore. That’s part of how he ended up on Hokule’a.

But only part.

At 6:20am, the first closeout set hit.

A Bay closeout is an amazing thing. The horizon darkens and lifts, like a cloud is passing across the sun. Then you realise it isn’t a cloud.

The second wave of the set shut down the entire bay, faded slightly as it rolled, and half-reformed off the left side, everything moving slowly, or seeming to, the way truly big waves always seem to happen in slow motion. Until they get to you.

Twenty minutes later, Clyde stepped down out of the judging tower and with great gravity, announced what the now 30,000-strong population of Waimea Bay had pretty much already guessed: “The Eddie will be on.”

Hannah and I roamed, with her big cinema-quality camera and my notebook, following our noses around through this astounding blue-sky morning, as the wind gently died off to glass, and set after set poured into the Bay — one every six minutes, every second one closing out.

The whole scene quickly resolved itself. On the one hand there was the humanity: that massive crowd, gathering along what passes for Waimea’s foredune, climbing rocks and trees in order to get a better look, and occasionally being caught by a surge of water from a closeout set, while the lifeguards issued stern warnings on the tower PA: “Stand back! Down in the corner, watch this surge!”

On the other hand was the surf zone, almost impossibly majestic and terrifying, a constant presence even if you tried to avert your gaze — not that anyone could, at least not for a good while that morning. It was like watching a wildfire from a place just too close for comfort.

In between was a foam-swept DMZ, a space where nobody lingered. You crossed that space at a run, or at as much of a run as you could muster, and you did not stop until you were in the water or well clear of it.

Theatre at its grandest.

Can you imagine being an invitee at such an event? The invitees didn’t have to imagine it. They were in it, even though not everyone knew who they were. Emi showed up at the check-in tent to get a pass and had to convince the lady behind the desk that she was actually there to surf.

Mike Ho and Billy Kemper formed a little two-person team. It was hilarious to watch. Billy took great delight in helping Michael figure out an inflation vest — Michael, the only surfer in the event to have surfed with Eddie, the living embodiment of a time when you just wore boardies and hoped your legrope didn’t break. In turn Michael was totally intrigued by the device, though when he actually tried to use it, the thing didn’t inflate. “I pulled it, and nothing happened!” he told an even more delighted Billy later.

But Ross was the surfer who broke the day open. It took a while before anyone got Waimea’s range on January 22. Water was pouring into the Bay with each successive closeout, then trying to escape around the shallows of the reef and out to sea, turning the normal takeoff zone into a huge draining rip bowl. Fighting that water was a crazy person’s game, but people were trying — nudging in close to the reef, battling to catch one and mostly failing, then having to dash back out to get over the next closeout set.

But Ross got a lucky break — a 20-minute lull, right at the start of his heat. During the lull he’d made a deliberate choice not to chase insiders the way his heat-mates did. When the horizon darkened again, he’d moved out and wide of the ledge. And boom.

It was the first big score of the morning, and it seemed to unlock something. Within an hour three 10s had been scored. Within another hour, people were taking off on things they shouldn’t have thought they could make, and occasionally they were right.

Watching this first phase of January 22, it steadily dawned on me — the genius of what Clyde and Liam had done. Not only had they busted open the Eddie to women like Emi and Paige Alms and Keala Kennelly, they’d busted open the entire invite system. Suddenly there was Jake Maki, the 18-year-old goofyfoot with a permanent grin and a pure stoke attitude, the gifted Keali’i Mamala, and 60-year-old Bay veteran Chris Owens, who came off the alternates list after Kelly Slater pulled out.

None of these people would have been invited to an Eddie in the past. Nor would Luke Shepardson, quiet and little-known outside his circle of fellow chargers — Luke who unlike any invitee in any Eddie ever, actually had a job. “I had to earn my time off today,” he told us later, smiling almost shyly. “I got three hours!”

Thus, Luke spent most of January 22 in the red and yellow lifeguard uniform, warning the crowd of big sets, anticipating problems, patching up surfers as they came in bleeding or shaken, or just watching the scene unfold from the lifeguard tower, from the same angle Eddie Aikau would once have viewed the Bay.

Full story available in SW420, on sale here.